The NHS has been given a real terms funding increase of £20.5bn over the next five years. In exchange, ambitious and stretching improvements will be required which demonstrate a clear improvement on this investment to the government and the public. Whether the money is enough to fund the expectations set out in the forthcoming long-term plan will depend largely on whether the NHS can free up resources by cutting waste and becoming more productive.

The improved funding package for the NHS, which was announced by the prime minister in June, offered 3.4% average real terms growth over five years. This is significantly more generous than any settlement offered to any other public service and recent NHS funding increases. However, it is below the long run average NHS funding growth and will barely allow existing models of care to keep pace with rising demand (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018).

The NHS is currently struggling on most major finance and performance indicators:

- the 95% for A&E waiting times has not been met since July 2015 (NHS Providers, 2018)

- in June 2018 the 18-week waiting list is likely to have been around 4.3 million (NHS Providers, 2018)

- the target for 92% of patients to wait no more than 18 weeks from referral to treatment has not been met since early 2016 (House of Commons Library, 2018)

- the provider sector has recorded a deficit for the last five years while CCGs have recorded deficits in two of the last three years

- the provider sector finished almost £1bn in deficit in 2017/18 (NHS Improvement, 2018)

- the underlying deficit now stands at £4.3bn. (NHS Providers, 2018)

The improved funding package for the NHS which was announced by the prime minister in June offered 3.4% average real terms growth over five years. This is significantly more generous than any settlement offered to any other public service and recent NHS funding increases.

Trusts are confident that the long-term plan can set out a vision for a transformed and sustainable NHS – but, to be deliverable and have credibility, it must give trusts a realistic and achievable task on efficiency. We must learn the lessons from past policy initiatives including the Five year forward view where realising expected efficiencies has proved problematic.

The Five year forward view won widespread support with its vision of a more prevention-focused health service. However, delivering this vision has proved difficult, in part because of the plan’s over-optimistic assumptions of how much the rate of efficiency could increase. For the budget to balance, the government’s injection of £8bn real terms growth over five years depended on the NHS delivering an unprecedented 2-3% rate of efficiency compared with a long run average of 0.8% (NHS England, 2014). Service redesign on the scale required, and the timeframe for releasing efficiencies from new models of care, turned out to be more complex than envisaged.

In addition, since funding began to be constrained in 2010/11, there has been a national assumption that deflating the tariff, and other payment mechanisms, would cause an acceleration in the annual rate of efficiency savings achieved by the provider sector and that doing this consistently over a number of years would generate a sustained rate of efficiency above the long run average achieved by the service.

Trusts are confident that the long-term plan can set out a vision for a transformed and sustainable NHS – but, to be deliverable and have credibility, it must give trusts a realistic and achievable task on efficiency.

To some degree this has proved successful as in the three years up to 2017/18 trusts delivered £6.9bn efficiency savings - £2.3-2.4bn of sustainable, recurrent efficiency savings each year (NHS Improvement 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018). However, in part as a consequence of the tariff deflator, in 2017-18 102 trusts (44%) finished the year in deficit, with financial deficits now the norm in the acute sector. In addition, trusts have become increasingly reliant on unsustainable one-off, or ‘non–recurrent’ savings such as technical accounting adjustments, land sales, vacancy freezes and delaying essential maintenance works to deliver the efficiencies required.

The debate around NHS efficiency is often based around a single, headline efficiency requirement for the whole NHS, which trusts believe is over-ambitious yet national leaders feel is appropriate given that waste exists in the system.

As the NHS develops its new long-term plan, we believe it is important to have a more sophisticated debate on efficiency. It is frontline NHS trust leaders who have to own the efficiency task and deliver the required savings. If they do not feel ownership of the task, or if they feel the nationally set task is undeliverable, then the potential for greater efficiency can be easily lost.

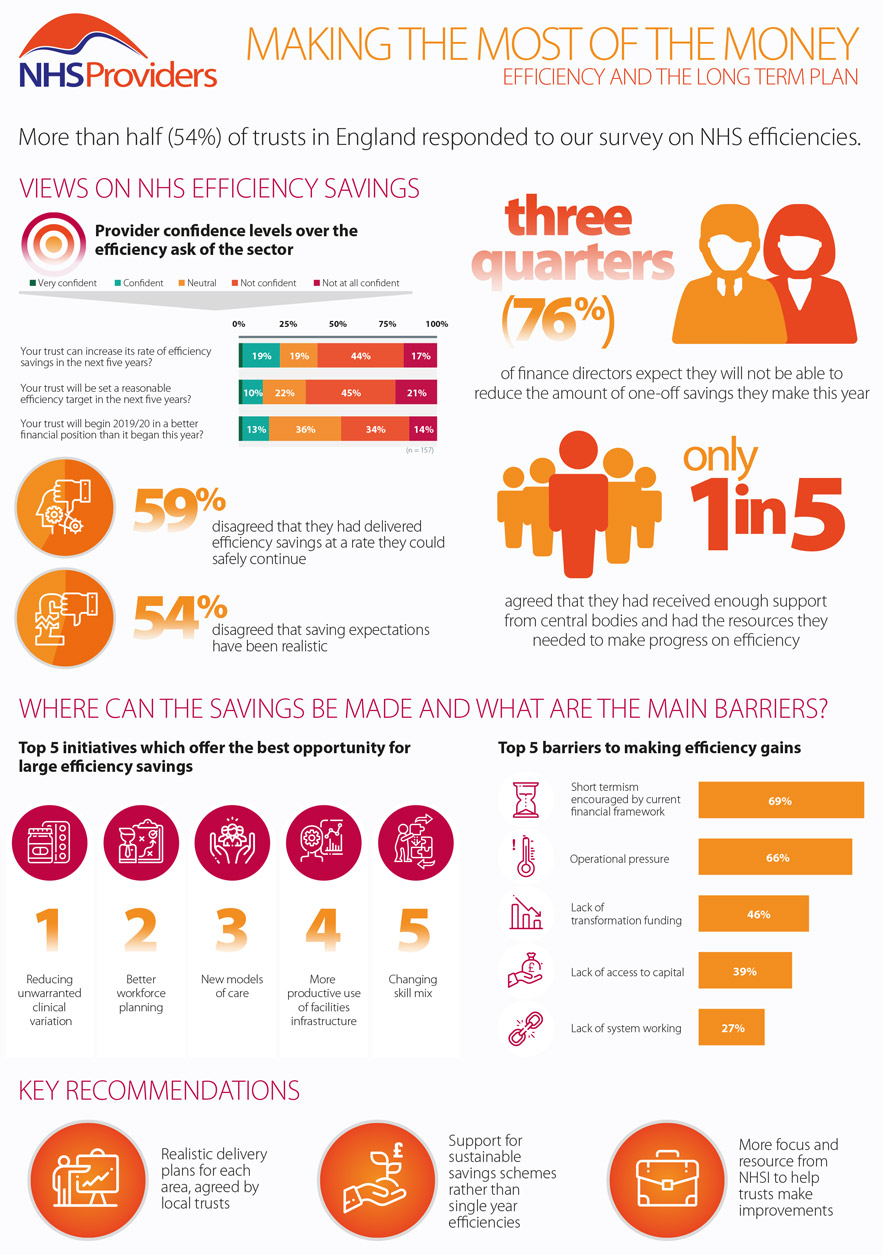

As the membership organisation for the NHS provider sector, we have used our unique access to trusts to explore the efficiency issue in depth – using a quantitative survey and a series of qualitative interviews. This document sets out the views we have gathered from trusts. It aims to share the trust level perspective to better inform the policy debate in this area.

The debate around NHS efficiency is often based around a single, headline efficiency requirement for the whole NHS, which trusts believe is over-ambitious yet national leaders feel is appropriate given that waste exists in the system.

The survey was completed by 157 provider leaders, representing 54% of trusts and foundation trusts. This work, carried out between July and September this year, forms the basis for this report and its recommendations. In our research we sought to find out:

- how trusts have risen to the efficiency challenge over the past three years

- how trusts feel about their ability to deliver an increasingly stretching efficiency requirement

- where savings can still be made;

- what national leaders can do to help trusts and local systems become more efficient.

This report examines these issues over six chapters. The first examines current performance on efficiency and productivity and how confident trusts are that it can be sustained. The following three chapters explore the opportunities offered by three main categories of efficiency providers cited: reducing costs, making existing services more productive and restructuring systems to make them more efficient. The final two chapters look at the approach taken by national leaders and provide a set of recommendations for the future.