Carolyn Regan

chief executive

West London NHS Trust

Background

Until recently the trust specialised solely in mental health services, but has recently expanded into wider integrated care, including community nursing services. It covers the London boroughs of Ealing, Hammersmith and Fulham, and Hounslow. Broadmoor Hospital, one of only three high-security psychiatric hospitals in the country, forensic services and specialist units, such as The Cassel Hospital, caring for people with personality disorders, also fall within its remit.

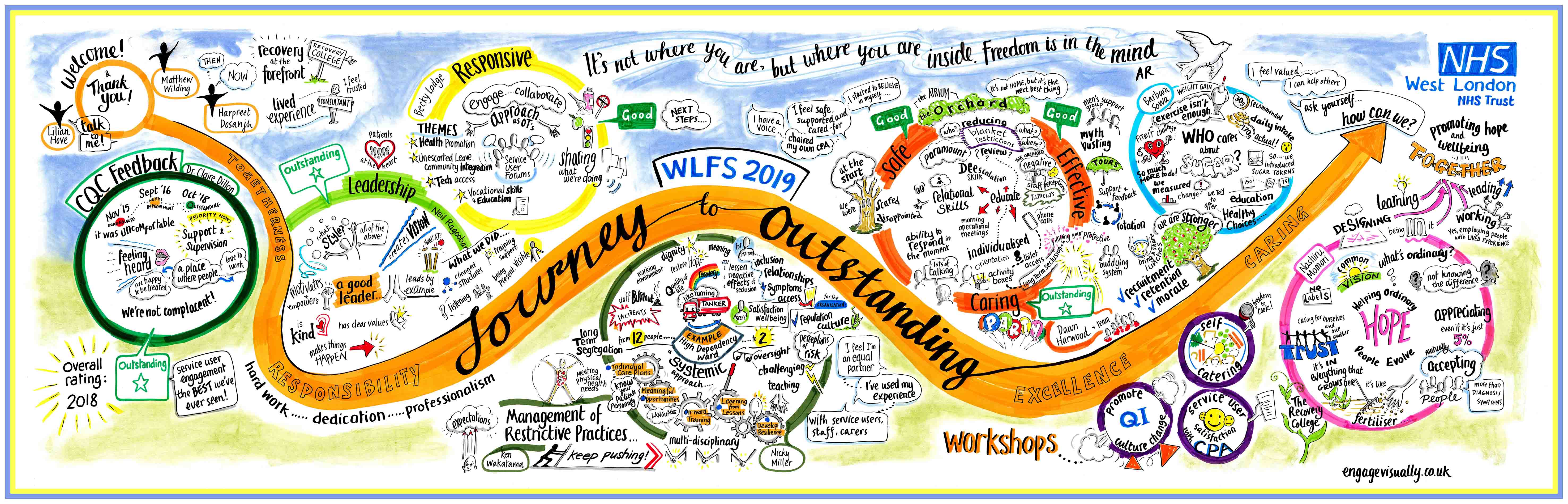

A 2015 CQC report said Broadmoor and the forensic services were inadequate, with poor staff engagement and inadequate staffing levels. Over three years, the forensic services, which were specifically criticised by CQC, went from ‘inadequate’ to ‘outstanding’.

A 2018 CQC inspection rated the trust as ‘good’ overall and ‘outstanding’ for caring across the board although safety still required improvement due to staffing levels in some areas and the quality of some of its physical environment, with some buildings pre-dating the NHS. Inspectors mentioned the strong, cohesive senior leadership team with a chief executive officer who was “an inspiring leader”.

Financially, the trust is more secure than many, with a surplus of just over £6m in 2017/2018.

Night owl

Carolyn Regan, an experienced senior NHS and public sector manager, joined the trust as chief executive in December 2015, a ‘new broom’ after the damning CQC report.

“Number one priority was to address the CQC report,” she says. “Our ethos was that money goes with quality and we can’t do them separately. We also needed a complete change of culture across the organisation.”

Her team’s strategy was “basically written on two sides of A4”, she says.

Carolyn set up meetings with the clinical directors to talk about quality and money, to go through their budgets, cost improvement programmes and find out what they were doing to address the findings in the CQC report and quality improvement.

“At first the clinical directors wondered whether they needed to meet me every month, and there was a bit of obfuscation. But it was about bringing everyone together to share issues, such as high bed occupancy. They needed to see that the problem couldn’t be solved by moving it around; we had to work on it across the whole system.”

The management team also set up quarterly leadership forums, to discuss what more visible management looked like – including promoting initiatives that made a real difference for patients. Similar meetings were held with middle managers.

“As well as running listening events and daytime walkabouts, I do night walkabouts, at three am. The first time I did that I thought people were going to keel over seeing me coming through the doors. I wanted staff to see me living the values: that transparency included the night staff, not just people coming on at 8am.”

The 2015 CQC report was, she says, a catalyst for improving quality, one of their key objectives.

Changing restrictive practices

The trust’s forensic service – caring for people who have been admitted to hospital under the Mental Health Act after coming through the criminal justice system – came in for criticism about the use of restrictive practices in the CQC’s 2015 report.

Yoke Wong, Lilian Hove and Albano Cabral, practice development nurses in the forensic service, have led on the work to improve practice. Their team has come together since the CQC report highlighted the over-use of restraint and patient seclusions.

Among their projects is Safewards, aimed at reducing conflict, improving patient involvement in care plans, and setting up a recovery college which encourages collaborative learning between staff and patients.

The Safewards approach was designed by Len Bowers, professor of psychiatric nursing at South London and Maudsley NHS Trust. It encourages more thoughtful use of language with patients and developing a ward environment and working relationships with service users aimed at reducing conflict and the need for services.

“We started the Safewards initiative around the time the 2015 report came out,” says Albano. “The original trial showed that acute mental health wards could reduce conflict by 15% and the use for restrictive practices by 26.5%. But this was the first time the model had been used in a forensic nursing setting. We started small with a pilot on just six wards. We found it worked.”

His findings – mainly qualitative data based on focus groups and patient feedback – were reported in the British Journal of Mental Health Nursing. The study concludes that on the six wards where Safewards interventions were used, there was a positive change in the community’s experience of safety, therapeutic hold and group cohesion.

“In the last year, it’s really moved forward and we now have this approach on all 19 wards.”

The forensic service is also leading the way on co-production and involving service users more in their care, says Yoke.

“We were getting feedback that there were some concerns with the care programme approach (CPA). Service users and carers didn’t feel involved in the process.”

A comment by a consultant psychiatrist to a service user unexpectedly triggered a range of changes to the culture and practice in CPAs. Following a CPA meeting, the consultant told this service user that she could have chaired the meeting herself. So, at the next CPA meeting, she did. After Yoke promoted this in the in-house magazine, other service users have been encouraged to become more involved in their CPA, with some either chairing or co-chairing it.

The original trial showed that acute mental health wards could reduce conflict by 15% and the use for restrictive practices by 26.5%. But this was the first time the model had been used in a forensic nursing setting.

practice development nurse

Yoke has set up a survey monkey audit tool to measure how many service users feel more involved in their CPA. Accumulative data from July 2018 to September 2019 shows that 84% (45) of the 51 service users who responded felt involved in discussions important to them. 80% (41) were clear about their goals for the next six months. And 70% (36) were given a chance to contribute to their care plan.