Current position on race equality

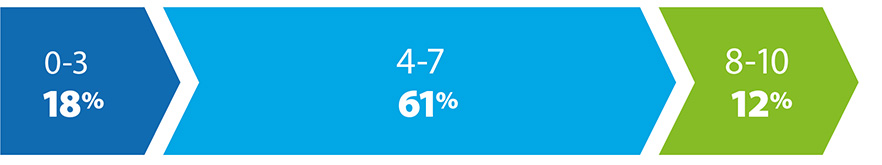

We asked survey respondents how they would describe their boards current position on race equality on a scale of 0-10 (early in your journey to fully embedded). Most felt they were mid-way in their journey, with an average rating of 5.6 overall (6.2 for chairs). Only 22% of respondents scored their progress highly (between 8-10), including just 4% who said that race equality is fully embedded as a core part of the board's business.

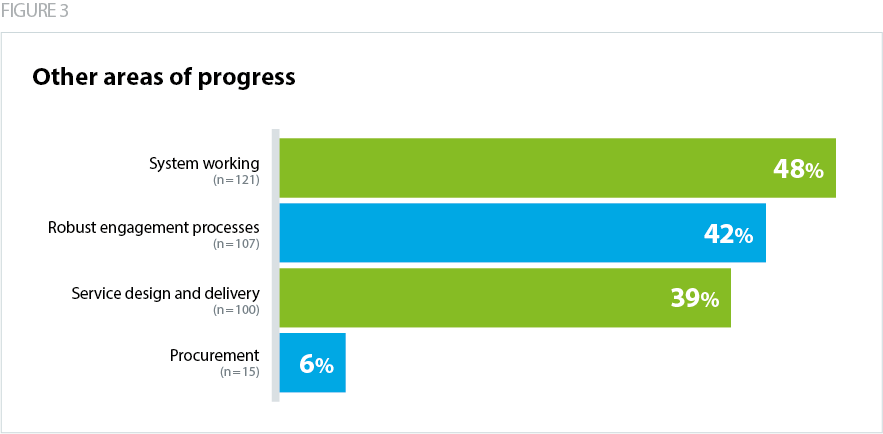

Leadership and governance

Figure 1 shows the areas where trust leaders feel their trust has made the most progress on leadership and governance actions on race equality. Just over four out of five respondents (85%) said an increased leadership focus on staff networks and 63% said they had progressed in building more diverse boards. Just less than a third felt that they have incorporated race equality into their board assurance framework.

Increased focus on staff networks and feedback

Leaders described their desire to hear directly about the experiences of staff and use this insight to prioritise actions and judge impact. Staff networks are increasingly being used to feed back on board thinking and EDI initiatives.

Staff networks ascribed to job role e.g. EDI leads, are being used to develop and share good practice and translate learning into tangible change, often supported through active sponsorship by board members. All have helped engender greater trust, fostering good relationships and good discussions with the board. Some staff network chairs are directly involved in senior leadership appointments.

Reverse mentoring was mentioned by some as an important way of “hearing from the people who experience the problems on the ground”, but some were much more critical of it being potentially tokenistic and placing the burden once again on ethnic minority staff to share, often traumatic, experiences of racism.

Building a more diverse board

Most leaders agreed that building a more diverse board was not only a key priority for the board but a personal priority. How people achieved this varied. Some ethnic minority leaders felt 'leading from the top' was an advantage in terms of being able to talk about their lived experience, as well as relate to the experience of ethnic minority staff; that it sent a powerful message.

Others talked about striving for their board to be reflective of the local community, 'needing something different', and taking active steps to achieve this. Another trust focused on proactive development of their internal talent, acknowledging that there were current senior ethnic minority staff at the trust who would benefit from being a NED.

Prioritising inclusive leadership development

Trusts talked about the good progress they have made with implementing inclusive leadership development programmes. Most were targeted at specific pay bands or groups, with some leaders describing how they extended programmes out to further groups after initial success. The programmes described ranged from six to 18 months.

One leader described having to call up people individually to ask them to sign up, while another made sure the cohorts were a mix of people they knew were fully on board and others who were not, so they could help and influence one another.

A clear strategy and plan on race equality

Some trust leaders talked about the challenge of ensuring they had a coherent action plan that drove impact on race equality. For most, an action plan rarely ventured beyond the Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) data to look at embedding EDI throughout the organisation. However, for some this ranged from: 'a comprehensive programme of work with clear expectations set by board and individual commitments from each of them'; 'a diverse board covering a range of protected characteristics'; to inclusive management strategies and 'empowered staff networks.' Leaders describe using very specific workstreams or a small number of priority areas to achieve their aims.

Actions to improve leadership accountability on race equality

Actions to improve leadership accountability on race equality started with a desire to have more meaningful conversations about race. Often driven by the chair, some leaders describe facilitating conversations internally, while some appointed an external facilitator. Some of the discussions, described as 'tense', involved myth-busting perceptions around positive discrimination practices and 'all lives matter' narratives.

One leader described how some of his board only engaged with the topic intellectually and not emotionally, but programmes were modified as people's engagement and understanding changed. Another leader described how a cultural intelligence programme at his trust included self-assessment of the board and involved training colleagues to become ambassadors. This helped individual board members understand their position and where they were on their own journey of awareness, confidence and capability to lead on race.

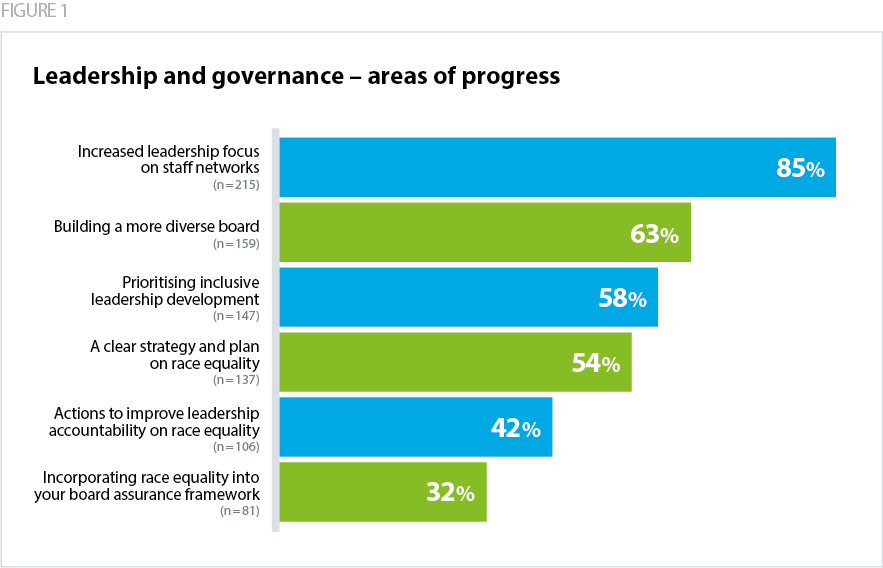

Workforce

Respondents were asked what progress they had made on race equality via workforce initiatives. Nearly four out five respondents (77%) felt that they have made the most progress in actions on improving workforce wellbeing. Only a fifth (22%) felt that they have made progress on retention.

Leaders recognised the need for staff wellbeing support particularly for those experiencing discrimination. One trust, for example, now requires all staff members below band six to participate in a Dignity at work programme as part of wider measures to address bullying and harassment. Another trust that focused on growing its minority ethnic staff network saw an improvement in how staff were impacted by racism.

A number have trusts have introduced work to support an ambition to be actively anti-racist. Initiatives include: leadership development to support an anti-racist ambition; internal antidiscrimination campaigns; and proactively calling out structural racism in the organisation and in services. Many leaders described driving improvements in workforce data, such as collecting more specific data on the makeup of the ethnic minority workforce and bullying and harassment. For example, one chair describes the introduction of inclusion days, where staff and external stakeholders were invited to review and discuss the WRES data together.

For some, developing inclusive recruitment practices arose from conversations with staff, which drove a different set of questions around recruitment such as, who do we engage with, and how do we involve a wider range of communities in the recruitment process? Others described how a staff network member sits on every senior recruitment appointment, and how changing criteria around recruitment has been critical in building a more diverse board and cohort of governors.

Using WRES data results as a guide, some leaders implemented specific actions on improving disciplinary and grievance processes and retention of ethnic minority staff. For example, one trust rewrote all HR policies – recruitment, appraisal, disciplinary and succession – with an emphasis on soft interventions and disciplinaries as a last resort.

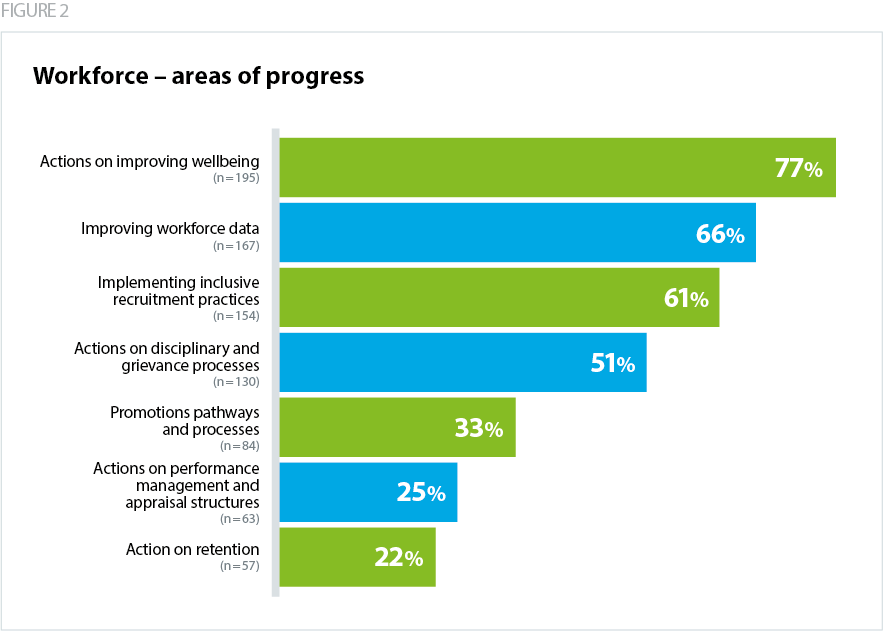

System working, community engagement, service design and delivery, procurement

Just under half of respondents (48%) felt that they had made progress in embedding an anti-racist approach into their work with system partners. A similar proportion (42%) felt they had robust engagement processes in place to involve ethnic minority communities in for example, monitoring levels of satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and access to services.

Just over a third of respondents (39%) felt that they had progressed with the redesign and delivery of services to local diverse communities for example, using data on local communities to inform strategies, policies and practice and assessing their impact. Only 6% (15 respondents) said that they felt they had made the most progress on procurement. This included monitoring all suppliers by race, including recruitment companies, and seeking commitment from service providers on race equality.