- The impact on health inequalities among patients should be considered and set out prior to any changes in the commissioning or provision of health or social care. Tools from NHS England and PHE, The Association of Directors of Public Health (ADPH) and the Local Government Authority (LGA) may be helpful in this.

- Any interventions should be delivered as part of integrated, co-ordinated person centre care.

- Services – and recovery actions – should be made accessible for all, particularly those at risk of exclusion because of personal, economic or social factors with resources for those with most unequal access and outcomes.

- Where there is any flexibility, health and care services should always be allocated based on healthcare need, striving in particular for equity of outcome, with a principle of proportional universalism embedded.

- Wider determinants of health should be addressed and funded at a place-based level, harnessing available community assets. These assets may include libraries, community groups, education centres, leisure and sport facilities or resources to support local families.

- Health and care staff should be valued and supported to maintain wellbeing and to enable delivery of high quality, person-centred care in all settings.

Why this is important

There is increasing awareness that COVID-19 has had a greater impact on disadvantaged populations. Health and care services need to consider mitigating any inadvertent impact that could arise during the pandemic response, which could risk an increase to existing population health inequalities. Some contributory factors highlighted for the increased impact of COVID-19 on disadvantaged populations include higher levels of occupational exposure, overcrowded housing, and insecure employment, which can also affect an individual’s ability to isolate or quarantine. There is broad recognition of the toll that the COVID-19 response is taking on the NHS workforce. In many areas of the UK, NHS staff (particularly those in pay bands 1-4) and patients may often be synonymous populations. This is particularly relevant for NHS trusts in the most deprived areas, where the health and care workforce often comprise 7-8% of the local resident working age population. Where workplace health or support incentives are offered, NHS trusts could also consider reviewing how these are organised, to maximise opportunities for supporting the wellbeing of all staff, and in particular those in pay bands 1-4, recognising this may include workforce from outsourced services. If trusts can also consider their own workforce as part of activity to identify local population needs, this could both help extend the reach of their workplace wellbeing offers and also strengthen contributions to improving the health of their local population.

Health and care services need to consider mitigating any inadvertent impact that could arise during the pandemic response, which could risk an increase to existing population health inequalities.

Workforce case study

The Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust had identified that a universal workplace health approach can lead to some hidden inequalities in uptake. They discovered only 10% of staff in Agenda for Change (AfC) bands 1-2 working at the trust were participating in the Fit at the free workplace wellbeing programme, while the cycle to work scheme was found to have a 91% take up amongst AfC bands 7 and above. To address this a ‘health as a social movement’ programme was developed, which included focused wellbeing activities for the facilities workforce across the trust (further detail in appendix 1).

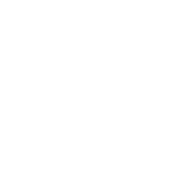

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected particular groups, including men working in elementary occupations such as taxi drivers, bus drivers, chefs and retail assistants, who were found in 2020 to have the highest rate of COVID-19 related morbidity. Also people of BAME populations have been found to have a significantly higher risk of death than those of white ethnicity (Black males 3.3 times higher, and Black females 2.4 times higher)1. A series of COVID-19 outbreaks in factories during summer 2020 highlighted an association between the virus outbreaks, working conditions and insecure employment. Pre-COVID, one in nine people in the UK were either self-employed, employed via an agency, casual or seasonal arrangements or were subject to zero-hours contracts. All of these factors can affect an individual’s ability to isolate or quarantine if they have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Figure 2 outlines some of the direct and indirect ways that COVID-19 and the incident response has been found to exacerbate existing health and care inequalities.

Figure 2

Impact of COVID-19

Effect on wider determinants and wider social care support systems

- Reduced ability to follow guidance in some communities because of financial, housing or social pressures.

- Staff shortages that affect deprived areas more.

- Reduced support from the voluntary sector.

- Decline in physical health e.g. from reduced/limited physical activity and poor diet -particularly neighbourhoods with limited green space, existing levels food poverty.

- Socioeconomic impacts of discrimination and its effect on the physical and mental health of those subject to discrimination including those with protected characteristics, and the wider impact across communities from this.

- Worsening child health due to school closures and an increase in risk for children known to social services or vulnerable, due to a loss or reduction of school support.

- Educational disadvantage in children.

- In the medium- to longer-term, a disproportionate impact on employment and income as a result of job loss and economic downturn.

- Social isolation as a result of lockdown and social distancing measures, and among clinically vulnerable and extremely vulnerable patients.

- Mental health impact of lockdown, including as a result of pressures from a loss of income. This can particularly affect NHS providers given the increase in local population mental health service needs.

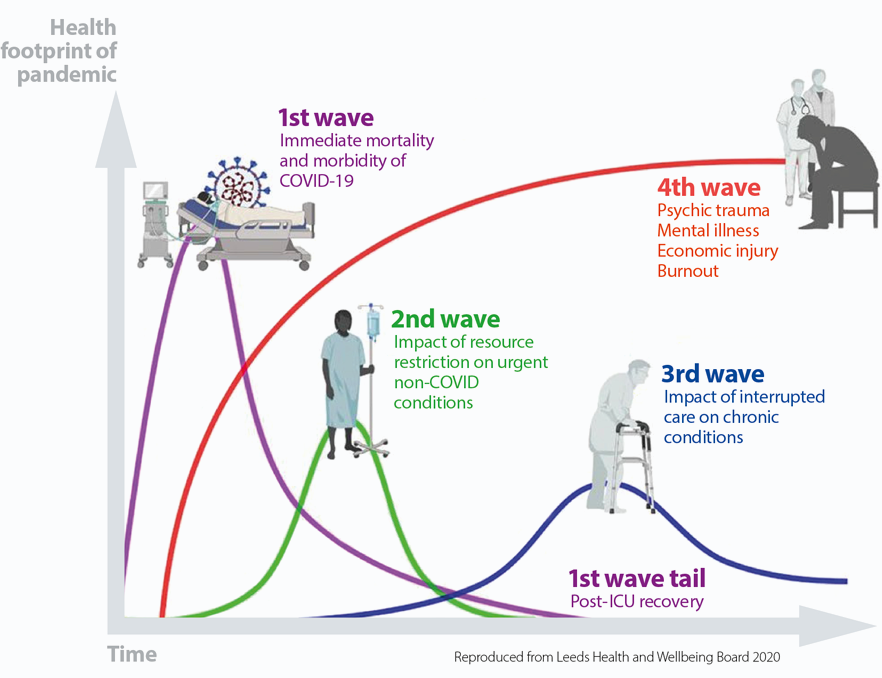

Figure 3

Impact of COVID-19 on health inequalities