Community services are a fundamental element of the system’s architecture, however there is insufficient understanding of community services and the community health provider sector among the national bodies, the Department of Health and Social Care, commissioners, politicians, patients and the public. This is partly because the community sector is characterised by its diversity, which can be attributed to the fact that there are many types of community services, many different types of providers, a range of commissioners and a multiplicity of contracts.

In addition, community services are often provided across several different geographic areas (footprints) by the same provider, or different sets of services are provided in the same footprint by each different provider. Broadly speaking, community service providers deliver a range of services across a range of footprints. However, this diversity should be celebrated and not act as a barrier that impedes our understanding of the role and importance of community services.

What are community services?

Community services deliver a significant proportion of NHS care in England, totalling 100 million contacts every year (The Health Foundation, April 2017). However, the scope, breadth and impact of the community health offer is often not well understood at a local or national level.

There are several reasons why community service providers – both trusts and CICs – face a key challenge to describe themselves and their place in the health and care system:

- Community services encompass a heterogeneous group of physical health and care services that are delivered in a variety of community settings such as clinics, community centres, homes and schools. This complexity makes it unhelpful to reduce them to a single, simple definition.

- Community services are not easily grouped together as they cover various different types of care that span a person’s lifetime, from macro-level public health services for whole populations, to micro-level specialist interventions for individuals with long-term conditions, as well as rehabilitation following hospital admissions.

- A diverse range of organisations deliver community services. These organisations may have some services in common, but often provide a large number of different services.

- Community services do not have the same propensity to make headlines, impact elections or generate national controversy as hospitals do; they do not have a distinct clinician body, so they are often missing from policy and public agendas.

The scope, breadth and impact of the community health offer is often not well understood at a local or national level.

Due to their diverse nature, the community health provider sector has often been subject to sweeping generalisations and narrow simplifications, and has historically been described through the deficit lens of what they are not, such as 'out of hospital' or 'non-acute' services, rather than what they are. This phraseology does not do justice to the breadth of services offered in the community and the wide-reaching impact they have on people’s lives (which is often described, in an echo of the NHS’ founding premise, as "from cradle to grave").

For the purpose of this report, our definition excludes services provided by GPs or mental health teams, but includes some local authority-commissioned services. We recognise that in reality, local arrangements are far more complex than this artificial separation of mental and physical health and that community teams work particularly closely with primary and social care.

Mental health services are an important component of care delivered in the community. Mental health trusts often deliver a wider range of community services, which themselves fit well within the personalised nature of mental health care. There is a specific set of issues around delivering mental health services in the community. For example, there are concerns about capacity as some mental health support services in the community are being decommissioned. While we decided not to cover these issues in detail in this report, the experience and learning from community mental health teams has much to offer to the transformation agenda of community services.

Mental health trusts often deliver a wider range of community services, which themselves fit well within the personalised nature of mental health care. There is a specific set of issues around delivering mental health services in the community.

As organisations move towards integrating care across organisational boundaries, this cross-sector approach to providing seamless care around a person’s needs is crucial. Indeed, some areas are drawing up an integrated care offer that spans the whole health and care system.

Given all this complexity, it helps to identify what makes community services unique. The most distinct feature is their connection to individual patients. Community services often have an ongoing relationship with a patient, compared with an episode of acute care. This has a knock-on effect on the ethos, dynamics and personalisation of these services. In addition, demographic changes, demand challenges and technological developments mean that staff are managing increasing levels of acuity and risk in people’s homes and community-based settings. They undertake complex decision-making in a highly independent way, and therefore push at the boundaries of traditional community nursing.

Another defining characteristic is that prevention in the true sense of the word is at the core of community services. This does not simply mean reducing emergency admissions, but rather preventing ill health and tackling health inequalities across geographies, communities and socio-economic groups. Strengthening community services is synonymous with a policy shift to prevention.

If hospital care is the illness service, then care in the community is truly the health service.

Community trust

Shape of services

The main types of services delivered in the community include, but are not limited to:

- adult community services (e.g. district nursing, intermediate care, end of life care)

- specialist long term condition nursing (e.g. heart failure, diabetes, cancer)

- planned community services (e.g. podiatry, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy)

- children’s 0-19 services (e.g. health visitors and school nursing)

- health and wellbeing services (e.g. sexual health, smoking cessation, weight management)

- inpatient community services (e.g. inpatient services).

The most common community services delivered by the 51 trusts providing community services that responded to our survey include community nursing teams (including district nursing), community specialist nurses, community physiotherapy and community palliative care. While these services are common to many trusts that provide community services, there are other services that were less common, including prison healthcare, sexual health services and school nursing.

Case studies

Given that the national picture of community service provision is so complex and, more importantly, community services are not a homogenous group, it is useful to take a deep dive into specific aspects of community services in order to demonstrate their role in the health and care system and the value they add. We have included case studies from the following trusts to illustrate this point:

- Cambridgeshire Community Services NHS Trust

- Bridgewater Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

- Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust

- South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

- Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust.

The most common community services delivered by the 51 trusts providing community services that responded to our survey include community nursing teams (including district nursing), community specialist nurses, community physiotherapy and community palliative care.

Shape of the provider landscape

The landscape of community service providers is often characterised in a negative way as complex, fragmented and atomised, with previous national policy initiatives to restructure services demonstrating how community services, following the life course of an individual, have never been a comfortable fit anywhere in the NHS. While there is often a main provider of community services in a local area, it is not uncommon for there to be several different providers running a variety of community services in the same footprint, or for a provider to operate across numerous footprints.

Out of the 230 NHS trusts and foundation trusts in England, we understand that there are 136 NHS providers registered by Care Quality Commission (CQC) to deliver community services (Care Quality Commission, March 2018); out of these we estimate that around 97 (42%) are providing a substantial amount of community services. These trusts include standalone community trusts and combined community and mental health or community and acute trusts. Of the 51 providers who reported in the survey that they provide community services, the average percentage of community health service provision at their trust was 50%. Trusts that solely provide community services reported that, on average, over 90% of the services they delivered were in the community. While trusts deliver most of these services themselves, a third of trusts providing community services reported that they subcontract some community services to other providers such as GPs, sexual health and palliative care services.

Trusts that solely provide community services reported that, on average, over 90 per cent of the services they delivered were in the community.

In addition to trusts, other types of organisation provide community services, including CICs, social enterprises and private providers.

The plurality inherent in this "mixed economy of types and sizes of provider[s]" means that there is a variety of models of providing community services to a local population; it depends on the local population size and demographic, the geography of the local area, and the local history of how services have evolved in the area, among other things (The King’s Fund, January 2018). This can be complicated as services can be fragmented, which can lead to them being badly co-ordinated from a patient’s perspective, and patients can be treated by different community providers within the same footprint. However, community service providers stress that the heterogeneous nature of community services is actually a strength, rather than a weakness.

The fragmentation of the community sector is also due to the private provider share of the community health service market being much larger than in other sectors of the NHS. Research undertaken by The Health Foundation (April 2017) showed that private providers tend to hold small, single service contracts in a particular area rather than very large contracts across a large footprint. In terms of turnover, NHS trusts hold over half (53%) of the total annual value of contracts awarded for community services. In comparison, private providers hold 5% of the total annual value (figure 1).

Figure 1

The Health Foundation, April 2017

However, in terms of the number of contracts, private providers hold the highest proportion of contracts – 39% of the total number (figure 2).

Figure 2

The Health Foundation, April 2017

These findings show that while private providers generally hold a large number of low value contracts, NHS trusts hold the relatively small number of high value contracts.

The shape of the provider landscape has also been affected by the development of new care models. One of the key challenges the vanguards addressed was how best to integrate community services with primary, social and mental health care across a geographic footprint to provide more joined-up care to the population. These forms of vertical integration include multispecialty community providers (MCPs), which deliver integrated services in the community through multidisciplinary teams of primary, community, mental health, acute hospital and social care staff, and primary and acute care systems (PACS) that bring together primary, community, mental health and hospital providers to better co-ordinate services for a local population. This blurring of the boundaries between all types of provision means it is important to see community services as part of the wider integration agenda. This is reflected through new care models, integrated care organisations, STPs and ICSs.

What does the community sector workforce look like?

Data on the entire community sector workforce is scarce. The most recent data is from 2008 which states that the community health sector employs around one fifth of NHS staff (Department of Health, July 2008). This workforce is predominantly non-medical, with the majority of staff being nurses and allied health professionals, but there are some consultant-led community services, such as sexual health services. There is also an increasing number of consultant roles that cross over hospital and community settings.

While the number of nurses in the acute sector has increased since the Francis report (Francis R., February 2013) and the subsequent drive to improve safety through staffing ratios, the community nursing workforce has decreased. Since May 2010, the community nursing workforce has contracted by 14%, which amounts to a loss of 6,000 posts. Over the same period, the workforce has grown in acute adult settings by 6%, representing over 10,000 posts (NHS Digital). Workforce capacity in the community needs to be strengthened before services can be expanded, but the nursing workforce, which plays a crucial role in community services, is shrinking rather than growing.

Since May 2010, the community nursing workforce has contracted by 14%, which amounts to a loss of 6,000 posts.

How community services are commissioned

The challenges facing community services are compounded by the fractured and complex nature of commissioning arrangements in the community sector. The commissioning landscape is comprised of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), local authorities and NHS England.

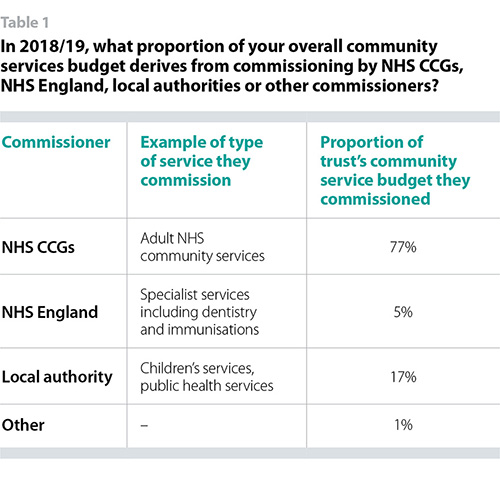

Respondents to our survey told us that the majority of their community service budgets are derived from their local CCGs (77%), while 17% of the budget came from local authorities and 5% was commissioned by NHS England (table 1).

While these findings are probably similar for other NHS provider sectors, the difference for trusts providing community services is that they hold contracts with a much higher number of commissioners. On average, trusts providing community services were commissioned by more than five different organisations, and for some this was as high as 10 commissioners. This fractured nature of commissioning creates additional burden for organisations delivering community services as it means providers spend more time managing contracts. Fractured commissioning also places a bigger burden on trusts as different commissioners have different requirements, with a more complex process of collecting information and reporting. It also means that commissioners will not necessarily have a strategic focus around community services.

The trust leaders that we interviewed reported that while some CCGs are striving to strengthen and expand community services, others are distracted by significant performance and quality challenges within the acute sector. This variability in CCG approach can mean that even successful, evidence-based initiatives to treat more patients in the community are not rolled out across a geographic footprint. Trusts across the country are striving to resolve this challenge through aligned incentive contracts and risk sharing agreements across all providers in a footprint. Other CCGs are encouraging community service providers to collaborate and bid collectively for a bundle of contracts, to overcome the risks of a disjointed community service offer in a footprint.

One of the key strengths of the community services sector is its diversity in terms of different providers delivering different services in a way that responds specifically to local needs. But the disadvantage of this diversity is that it makes it more difficult for policy makers, commissioners and politicians to understand and value the community services sector. If we are to achieve the stronger community services we need, opinion makers have to make more of an effort to understand and positively value this diversity instead of using it as an excuse to ignore or undervalue the sector.