Summary

Trusts are facing significant increases in demand for their services as a result of demographic factors, pressures on primary and social care provision and increasing patient expectations.

As a result, trusts are running at capacity levels beyond the recommended norm and levels in other western systems. Importantly, local health systems are less resilient and less able to absorb the shocks that any healthcare system inevitably faces, such as flu outbreaks or local care home closures.

When combined with financial and workforce pressures, this means performance on access standards is the worst it has been in a decade. This poor performance and demand pressure spans every sector and is affecting nearly every trust. The challenges are systemic rather than the result of poorer individual trust performance. But access to NHS services remains good against international comparisons.

The evidence on quality is mixed. A near complete set of CQC inspection data rates a majority of trusts as either requiring improvement or inadequate. The latest CQC State of care report argues for the first time that some services are now failing to improve and there is some deterioration in quality. But, overall performance in the latest CQC patient experience survey remains high and 95% of trusts are rated as having good or outstanding services in the caring domain of their inspection.

Trusts are undertaking a wide range of activity to meet these challenges. These include performance recovery programmes focusing on emergency care and elective waiting lists; greater support for primary and social care; introducing improvement methodology; support for trusts in quality special measures; and implementing recommendations of taskforces to improve cancer and mental health outcomes.

Trust chairs and chief executives are increasingly nervous about the future. They told our survey they are concerned that performance against the access targets cannot be sustained, let alone improved. Three quarters are concerned that the mismatch between resources and demand will, if not addressed, result in further deterioration in access to services and negative consequences for the quality of care patients receive.

Providers are stretching every sinew to deliver high-quality care but there is a danger they are unable to recover performance against the targets and that quality begins to deteriorate, potentially at greater speed. We risk losing the hard won improvement gains made between 2000 and 2010.

THE PROVIDER CHALLENGE

Pressures on demand

In recent years we have seen a sharp increase in demand for hospital, community, mental health and ambulance services. At the same time patients have higher and more complex needs – higher acuity. It is clear that a wide range of previous approaches to stemming demand, such as reinvestment of the marginal rate on emergency admissions, have signally and consistently failed.

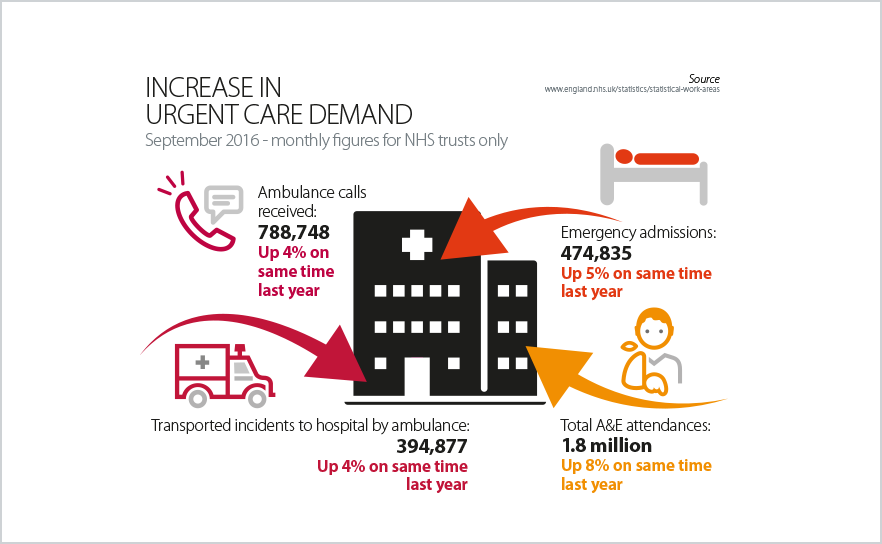

Not only is demand up, but the rate of growth of demand also appears to be speeding up. NHS Improvement reported that emergency admissions via A&E are 4% higher for the period July to September 2016 than in the same quarter last year. They also reported that the number of GP referrals has increased by 4% between July and September compared to the same time last year. Significant demand increases are also being experienced across all sectors. For example in mental health, 1.8 million people were in contact with mental and learning disability services in 2014/15, a 5.1% increase on the previous year. Community trusts report similar increases.

These levels of demand are a long way beyond NHS trust plans and the assumptions made in the NHS Five year forward view, published in October 2014. A recent NAO report, for example, pointed out that the Five year forward view assumed that growth in acute hospital activity would be reduced from 2.9% to 1.3% per year through a range of transformation programmes. However, as the statistics below show, demand growth is actually speeding up rather than reducing.

Reasons for demand increases

Trust boards report that they are unable to determine the precise reasons for the growth in demand and more complex care. Commonly cited reasons include:

- a growing, ageing population with increasing prevalence of multiple long term conditions

- a primary care system which is struggling to meet the demand being placed upon it

- a social care system which is widely accepted to have reached a tipping point due to funding cuts, increased demand, the pressures of the minimum wage and private providers exiting the market

- a society which has high expectations of its NHS, wanting ever faster access to a wider range of better services around the clock.

One important and urgent piece of work the NHS needs to undertake is a proper analysis of the reasons behind these demand increases and a better prediction of how they are likely to play out in future.

Capacity constraints and resilience

In the face of this demand growth, the NHS has been “running hot” for an extended period. Although trusts are working hard to keep pace with demand, the provider sector is operating at capacity levels beyond those which other international health systems would regard as acceptable. In the UK there are only 2.8 beds per 1000 people compared to an average of 5 beds being available per 1000 people across OECD countries, despite having very similar lengths of stay.

Bed occupancy levels on inpatient wards in the acute and mental health sectors therefore now frequently exceed the recommended maximum levels of 85%, often to levels higher than 95%.

This capacity constraint is further compounded by delays in discharging medically fit patients from hospitals. The trajectory on national statistics for delayed transfers of care in hospitals shows the scale of rising pressures facing hospitals from declining capacity in social care, with figures at their highest since first recorded in 2010. The latest performance data shows a record high of 385,634 bed days were lost as a result of delayed discharges – a 34.8% rise on the same quarter last year. However it is important to recognise that these delays can also be a result of poor transfers inside the NHS as well as between the NHS and social care.

Resilience is vital in any secondary healthcare system as it needs to absorb extra demand from frequent regular events such as winter flu outbreaks, the closure of local care homes, and the transition from retiring GPs to more risk averse, newer practitioners that can quickly lead to sharply higher referral rates.

The capacity levels at which we are now permanently running our hospital, ambulance, community and mental health services and the length of time for which we have been doing this has seriously reduced resilience. We are seeing precipitate drops in A&E performance in particular hospitals on particular days, which have a clear negative impact on patient experience and patient safety. Many are traceable back to an inability to cope with activity shocks that five years ago could have been absorbed but now cannot be.

This combination of substantially increased demand and capacity constraints, together with the harsher financial environment and workforce challenges, which we describe in chapters on finance and workforce, is leading to growing pressures on access and quality.

Access – what the statistics and evidence show us

Overall performance figures in the NHS are now at their worst in a decade and while there are recovery programmes in place, consistent delivery of the agreed performance standards is proving stubbornly elusive.

This drop in performance is marked by a number of characteristics:

- the large number of trusts missing their performance targets – failure to meet performance targets is now widespread, as opposed to just a few trusts missing targets

- the number of targets being missed – nearly all targets are now being missed, as opposed to just one or two

- the scale of dropping performance – targets are now being missed by a much larger margin than previously with higher numbers of trusts being significantly further away from achieving their targets.

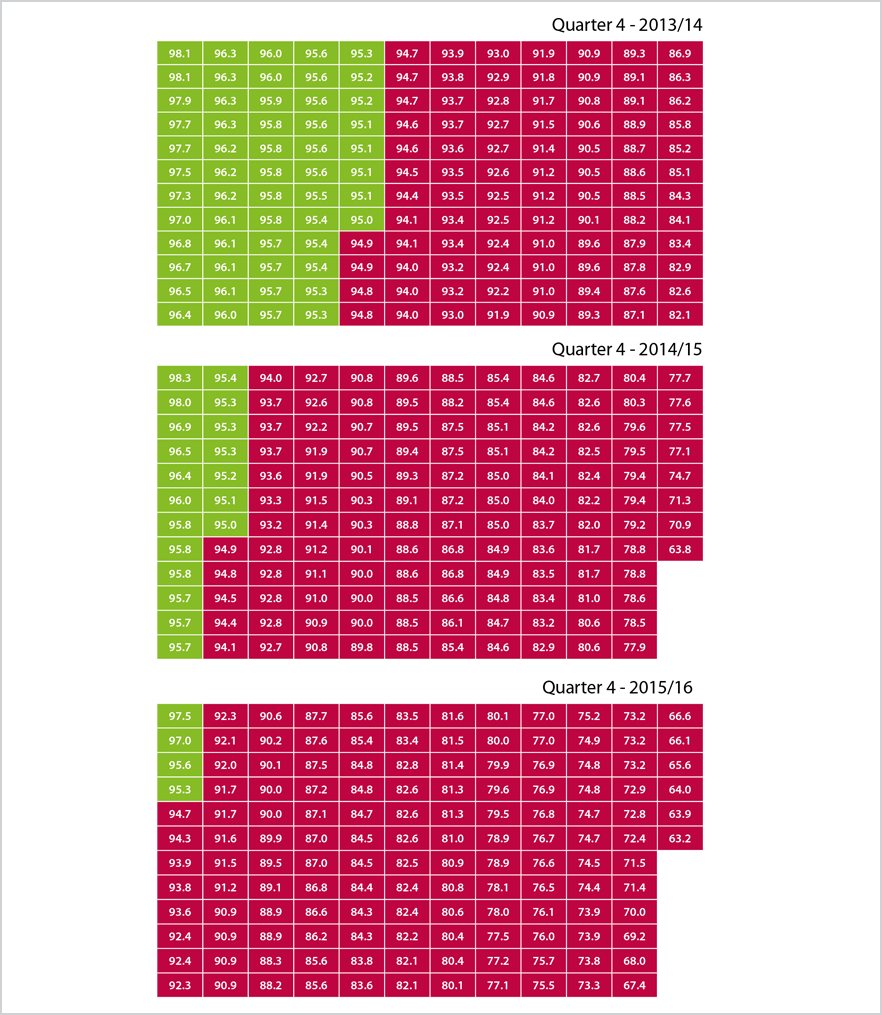

These trends are well illustrated in figure 1.1 which shows performance against the four hour standard across the major A&E departments in quarter 4 of each of the last three financial years.

The same profile is seen with key referral to treatment consultant-led waiting times where in September 2016, 119 trusts were meeting this target, compared to 154 at the same time last year. The latest data shows 9.4% of patients waited longer than 18 weeks to begin hospital treatment – this is the worst performance since targets were revised in 2012. This again indicates that systemic issues, rather than poor performance from individual trusts, are responsible for this deterioration in performance.

Ambulance services also continue to struggle to deliver the Red 1, Red 2 and 19 minutes response-time targets with performance of 68.6%, 62.1% and 90.5% respectively against targets of 75%, 75% and 95% of cases.

Performance data on access to mental health and community services is less comprehensive, but the available data, alongside trust reports, paints a similar picture of NHS trusts under heavy and rapidly rising pressures. For example, waiting lists for treatment and out of area placements, in particular for child and adolescent mental health services, are rising. As capacity stretches further, it is becoming harder for people needing mental health services to access them early enough to prevent

unnecessary deterioration.

Community trusts also report significant performance challenges across the full range of their services from district nursing to health visiting. This is being compounded by cuts to local authority contracts in areas like public health, sexual health, and school nursing.

However, from both an international and historical perspective this performance is still relatively strong. What is worrying is the downwards trajectory on performance and the persistent inability to recover the NHS constitutional performance standards. Trusts risk losing the substantial performance and access gains made over the last decade.

Figure 1.1: Increase in number of trusts not meeting the four-hour A&E target for type 1 services:

Quality – what the statistics and evidence show us

Access to services is not the only measure of performance. The quality of services is equally important. The evidence here is mixed. On the one hand there is significant evidence showing that the quality of service provision in the NHS is under pressure and potentially deteriorating. We have a near complete set of inspection results from the CQC with 225 NHS trusts now inspected.

The CQC uses a four category overall rating system. Four per cent of the trusts inspected so far are outstanding, 32% are good, 58% need improvement, and 6% are inadequate, showing there are questions around the quality of care being provided by nearly two thirds of trusts.

Looking at the results in more detail, as set out in figure 1.2, the vast majority of trusts (95%), have been rated as having good or outstanding services in the ‘caring’ domain.

Performance across the other domains is lower and more variable. Performance in the ‘safe’ domain is of greatest concern – 80% [or 88% of trusts were rated by the CQC as requires improvement or inadequate in this domain. This is a particularly important domain as poor performance on safety is a key driver for a trust to be placed in special measures, with 16 trusts currently in quality special measures.

Figure 1.2

CQC inspection ratings for quality of care

The CQC’s State of care report –its annual overview of health and social care in England – provides an even more up-to-date picture. The report states that, despite challenging circumstances, much good care is being delivered and encouraging levels of improvement are taking place. However for the first time it also argues that, due to the unprecedented demand and financial challenge, some services are now failing to improve and there is some deterioration in quality. The report also highlights questions around the sustainability of social care, and the impact this is having on the NHS.

Other evidence is more positive. Patient satisfaction with quality of care remains generally high. The latest inpatient survey results found that overall patient experience of adult inpatient services significantly increased between 2014/15 and 2015/16. Longer term, patient satisfaction with hospital care has made some modest gains but has declined in areas where pressures are well known, such as timely discharge and referral to treatment times. Public support for the NHS overall also remains high. Polling suggests that people generally perceive the quality of access and treatment in the NHS to be good, but remain concerned overall about its sustainability.

Responses to our survey of trust chairs and chief executives reflect these rising pressures. Figure 1.3 shows that two thirds of chairs and chief executives are confident they currently provide high-quality care. However, when chairs and chief executives look forward six months there is a significant drop, with only 46% of respondents thinking they will be able to provide high quality care.

Figure 1.3

How would you rate the quality of healthcare provided by your local area

Respondents to our survey highlighted that a lack of broader support and capability within their wider local system, particularly in social care, is posing a major problem for trusts. Respondents have highlighted that they are “very dependent on community capacity - nursing home and residential home beds” (chief executive, acute trust) and there are also concerns about the “inability of primary care to pick up work which could properly shift to them” (chair non-acute trust).

the provider response

Trusts throughout the country are taking the initiative to tackle these challenges and improve the quality of patient care in a number of different ways, supported by NHS Improvement and NHS England. Some of these initiatives are set out below.

Coping with and managing demand - a rapidly increasing number of trusts, of which Whittington Hospital NHS Trust is just one example, are providing medical care on an outpatient basis through ambulatory care centres. They are offering rapid access to diagnostic tests, specialist skills and treatment to prevent unnecessary admissions to hospital. Hospitals such as Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust are changing their model of accident and emergency care by using senior clinicians at the A&E front door to redirect patients to 111 or general practice, where appropriate.

Winter resilience planning - there has been a particular emphasis, both this year and last, on improving planning for the winter period when performance pressures are greatest. New urgent and emergency care system boards, often chaired by acute trusts and involving community, mental health, primary and social care partners are designed to oversee improved planning and delivery. A strong focus is ensuring appropriate primary and social care capacity over the Christmas and New Year periods to prevent hospitals being the only health and care facilities open over the holiday. There is also emphasis on communications to improve public awareness around the increased pressures on A&E and how to more proactively self-manage conditions to prevent people becoming more ill and to reduce the chances of unnecessary admission to hospital.

Improved accessibility and responsiveness to mental health crisis services - through street triage, single point of access for referrals, and 24/7 crisis care. Innovation in services is also driving improvement. Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust’s psychiatric decision unit provides a responsive seven-day service to people whose complex presentations and/or social issues mean immediate discharge is not possible.

Social care provision – NHS trusts are increasingly recognising that their performance is dependent on adequate social care provision. They are therefore improving collaboration with local authorities and other social care providers or are now providing social care themselves. For example Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust is leading the provision of a new form of integrated care for its old and frail population. They have halved delayed transfers of care following the introduction of a set of changes including directly employing social care workers to facilitate discharge into the community and purchasing capacity in the local care home market that they then intensively support. East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust is integrating teams of health and social care professionals, working closely together to offer personalised care in the community and supporting patients with long term conditions to remain out of hospital.

Primary care provision – trusts also are increasingly recognising that their performance depends on stable and robust local primary care, particularly general practice. Trusts are strengthening their relationships with GPs in a number of ways. Northumbria Healthcare, for example, has supported the development of a local GP federation, provides a range of back office services to those practices that want them and is also now designing roles for GPs which span both the Northumbria acute care setting and the GP’s local practice. Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust has now acquired three GP practices, at their request, covering 27,000 of the local population and is already reporting significantly improved patient pathways as a result.

Managing the flow of patients – a number of trusts are seeking to improve their patient flow, helping patients move more quickly from admission to discharge. These include approaches such as ‘proactive discharge planning’, used by Ipswich Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and ‘discharge to assess’, used by South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust. Both trusts use multidisciplinary care teams to rapidly ensure medically fit people are cared for appropriately in the community.

Performance recovery and outcome improvement programmes and initiatives - trusts are working closely with NHS Improvement and NHS England to deliver a range of agreed national initiatives and programmes to recover performance and improve outcomes. Examples include:

- Emergency Care Improvement Programme (ECIP) – this clinically-led programme provides intensive practical help and support to 40 urgent and emergency care systems, designed to enable them to deliver the required accident and emergency standards.

- Referral to treatment times (RTT)– there is a similar scheme to support trusts to improve their RTT elective surgery performance which is supplemented by regular waiting list initiatives frequently involving weekend and extra working by clinical teams to reduce the size of waiting lists.

- Cancer and mental health taskforces – trusts are now working to implement the recommendations of two key national taskforces designed to improve outcomes in cancer and mental health. In cancer the key emphasis is on improving early detection rates, living longer after diagnosis and a better experience of care and support. In mental health the focus is on introducing a series of access and provision targets such as early intervention in psychosis, talking therapies, eating disorders, liaison psychiatry and child and adolescent mental health services.

Special measures – particular emphasis has been placed on supporting trusts who have been identified as providing inadequate care to improve. Nineteen trusts have exited the special measures regime through consistent and usually rapid performance improvement against action plans, followed up by comprehensive re-inspections. Sixteen of those trusts that are currently in or have been through special measures have formal buddying relationships with other trusts to provide ongoing support on performance improvement.

Improvement methodology – trusts like Western Sussex; University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire; Shrewsbury and Telford; Barking, Havering and Redbridge; Leeds Teaching and Surrey and Sussex Healthcare are formally introducing Lean/continuous improvement methodology to improve services and patient care. The methodology equips NHS staff with the technical and analytical skills they need to understand, model and test changes in services to improve patient outcomes, care quality, efficiency, productivity and value.

The risks

As demand, financial and workforce pressures grow, there is a real danger that access and quality will deteriorate further and faster. For example, waiting times could lengthen, clinical thresholds for access to care could be raised, access to care could be rationed by commissioners, and unmet need for early intervention services could lead to delayed access, higher acuity and less effective care. Taken together this could bring about greater inequality and inequity, problems that we already know affect English health and care provision.

Our survey found that about three quarters of chairs and chief executives are concerned that the current mismatch between resources and demand will – if it remains unaddressed – result in further deteriorating access and negative consequences for the quality of care patients receive.

Figure 1.4

Over the next six months, how confident or worried are you that your local area can continue to maintain its current level and quality of services within the resources available?

Some trusts retain a positive outlook. For example, one chair of an acute trust said: “We are planning to deliver on everything but if it does go off, I would expect it to be the finances”. Others feel more challenged: “We remain very focused on it. But a complete demand management impact vacuum in both outpatients and emergency department places us under real pressure” (chief executive, acute trust). Overall, respondents to the survey were clear that achievements were largely due to trusts themselves having a “focus and grip” (chief executive, acute trust).

Trusts are increasingly making the connection between the financial squeeze the NHS is experiencing, as set out in the next chapter, and their ability to cope with the increase in demand and acuity they face. Recent research has shown, for example, that funding for mental health has been cut and that the promised funds for mental health services in 2015/16 were not received. Respondents to our survey had limited confidence that further funding will reach the front-line, for example:

CCGs are not able to fund the increased demand and higher acuity in mental health which is deteriorating our financial position. We have higher levels of delayed transfers of care because of lack of specialist placement available, so length of stay is increasing.

Trusts are working hard to deliver the improved performance that is needed to meet the required NHS constitutional performance targets. But feedback from chairs and chief executives responding to our survey shows that there is little confidence the required improvement can be delivered. Over two thirds of all respondents thought that performance against the targets would either stay the same or deteriorate, implying that performance targets will still be missed. Analysis of results by type of trust differ, which may reflect the absence of and relative lower emphasis on NHS constitutional targets in community and mental health trusts.

Figure 1.5

Over the next six months, do you think your trusts' performance against key access targets is likely to:

What providers need

No matter what sector they operate in, trusts need a smaller range of priorities and a realistic approach to delivery trajectories within them. For example it is clear that recovering the RTT elective surgery target will be significantly more difficult than system leaders are currently acknowledging.

Providers sit within a wider local system and demand can only be effectively managed across that system as a whole. Social care has reached a tipping point, with primary care not far behind, and both need rapid extra support to prevent demand being unnecessarily referred to the secondary care sector. Given the difficulty and complexity of the provider task, system leaders need to significantly increase the level of support given to providers rather than simply focusing on greater grip and control.