Over winter, the increase in demand for emergency care is often the main focus of public attention. However, increases in demand are felt right across the system, with additional pressure on mental health services, community services, primary care and social care. Winter planning is truly a whole system issue, as partners work together to try and treat people closer to home and reduce unnecessary admissions, and length of stay, in hospitals.

One consequence of the NHS system running 'hot' is that it severely restricts the scope to re-deploy resources – including beds and staff – to ease pressure on A&E. Resilience to deal with the inevitable spikes in demand is compromised. Trust leaders tell us that in the past it was easier to draw on spare capacity to soak up these extra pressures and they are working in new ways to try to keep up. The figures tell their own story – they are falling further behind.

Set out below is a range of performance metrics from across the provider sector which give an indication of these pressures. Where possible we set out the current position, the position last year and the position compared to the 2018/19 planning guidance.

Winter planning is truly a whole system issue, as partners work together to try and treat people closer to home and reduce unnecessary admissions, and length of stay, in hospitals.

Referral to treatment

- Performance against the 18-week standard is 87.2%, well short of the 92% target. The latest data we have, for the end of August, indicates there were 4.15 million people on the elective care waiting list – the highest since the data collection began, and 7% more than at the same point last year. It is also well above the level laid down in the planning guidance.

- There has also been a worrying increase in the number of patients waiting more than 52 weeks for treatment. The figure has almost doubled to 3,407 over the last 12 months, despite planning guidance stipulating that the number should fall.

Figure 1

A&E

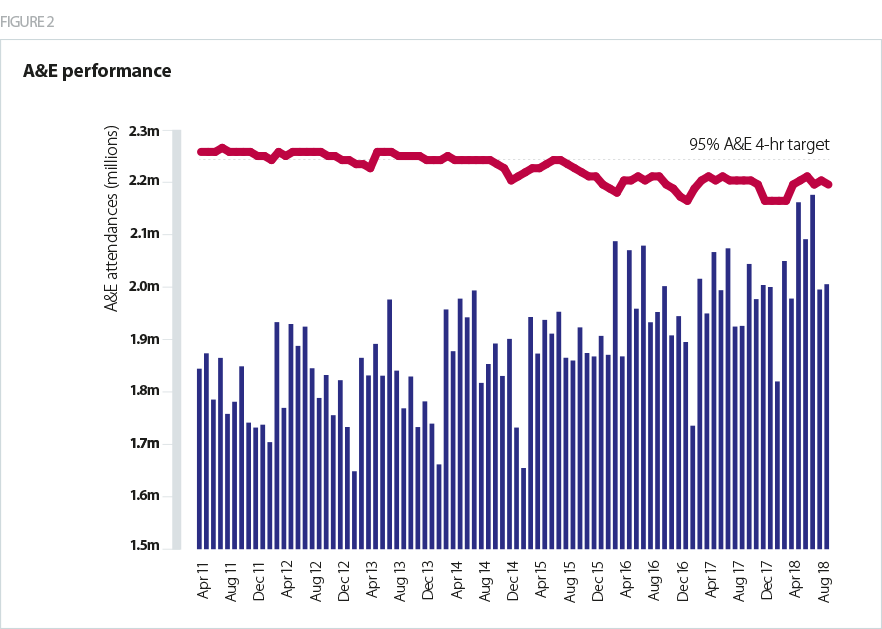

- There has been a steep and sustained increase in demand for A&E services. As recently as two years ago, national NHS leaders were worried by the prospect of attendances hitting 50,000 in a day. Last winter we saw 60,000 in a day and the average for July was 70,000 per day. We really have moved on.

- The challenges the NHS dealt with over the summer were borne out in the A&E performance figures. In September, 88.9% of patients were admitted, transferred or discharged in four hours for all A&E departments (compared with 89.7% at the same point last year). This fell to 83% for type 1 attendances – both significantly under the 95% target, and short of the 90% figure set for September in the NHS planning guidance.

- Overall emergency admissions also rose by 5%, though the increase in type 1 departments was close to 7%.

- There has been a concerted effort to extend same day (or ambulatory) emergency care. This provides for rapid access to diagnostics and clinical assessment without admission to a hospital bed, where clinically appropriate. The number of patients treated in this way has increased by close to 10% in the past year.

- However, the unavoidable conclusion is that trusts with urgent and emergency care services are entering winter from a more challenging position than they were last year.

Cancer

- There are currently eight main operational standards for cancer waiting times and three key timeframes in which patients should be seen or treated as part of their cancer pathway; two months (62 days), one month (31 days), and two weeks. The planning guidance sets out that the NHS should uphold all of these standards in 2018/19. As we head into winter, overall performance against the national targets is at an all time low.

- The NHS is currently missing five of the eight standards.

- The 62-day wait cancer target has been consistently missed at a national level since 2013/14.

- At the end of August performance against the 31 day standard stood at 97% - still above the 96% target but slightly down on where it was 12 months earlier.

Performance against the two week standard for urgent referrals had slipped to 91.7% against a target of 93%. At the same point last year performance stood at 94%.

Figure 3

DTOCs

- There has been significant improvement in reducing DTOCs. The planning guidance asks providers to continue to make progress on reducing delayed beds per day to around 4,000 during 2018/19, with the reduction to be split equally between health and social care.

- In August 2018 there were 4,697 delayed beds, a reduction of 19% on the same month the previous year, but still some way short of the target set. As the chart below indicates, there are worrying signs that progress has stalled.

- There is a continuing focus to tackle 'superstranded' patients (those in hospital for more than 21 days). Trust leaders acknowledge there is scope to make headway in reducing very long lengths of stay, but the targets set must be realistic.

Figure 4

Mental health

- Mental health trusts tell us that increases in demand combined with severe staffing pressures and the lack of suitable beds are resulting in costly out of area placements (OAPs). These are almost always inappropriate and may be distressing for service users and their carers.

- From the available data we know that between January and May 2018 there was an average of 650 OAPs started per month. The figures were highest over the winter months, reflecting increased pressures. OAPs cost the NHS an average of more than £8.3m per month over the winter last year.

- Mental health bed occupancy in quarter one in 2018/19 was 89.8%, slightly higher than 89.3% in the same period in 2017/19 – a further sign that pressures are at least as bad, if not worse, going into this winter.

Community services

- It is widely acknowledged that community services have a central role to play in both preventing and managing winter pressures, yet our recent report Community services: taking centre stage showed how many trusts were left marginalised, underfunded and short staffed.

- Community trust leaders tell us that the steep rise in demand coupled with the complex needs of people living at home are largely ignored and hidden. However, these problems often surface when these patients have to be picked up by ambulance and admitted to hospital as an emergency.

- This is explained, in part, by a lack of centrally collected and published data on community services, although trusts do collect and use performance and quality indicators at a local level.

- Community services have a key role to play in reducing DTOCs and supporting patient flow – and therefore easing pressures right across health and care in the coming winter. Our report pointed to a range of examples of where this is happening, but without further funding and focus, there is a risk that many more opportunities will be missed.

Mental health trusts tell us that increases in demand combined with severe staffing pressures and the lack of suitable beds are resulting in costly out of area placements.

Ambulance

- The growing pressures on ambulance services were a key part of the story of last winter for the NHS, as delays in hospitals caused problems further ‘upstream’. This resulted in record numbers of ambulances being diverted away from emergency departments that were struggling to cope.

- Another consequence was the spike in ambulance handover delays. Ambulances often struggled to hand over patients in the recommended time of less than 15 minutes because hospitals did not have enough capacity.

- Last winter there were 175,000 ambulance handover delays that were 30 minutes or more. These delays are a signal of system wide pressures and are often out of the control of the ambulance service.

- As we head into winter we see the same set of ingredients that contributed to last year’s problems - accelerating demand across health and care, with the risk that services will struggle once again to keep up, with ambulance services shouldering many of the pressures.

The wider health and care sector

- Social care. Social care faces a funding crisis which is having a direct impact on the NHS. The recent announcement of an additional £240m to fund care packages or home adaptations for people being discharged from hospital or at risk of emergency admission was therefore very welcome. However, according to the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) annual budget survey (Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, 2018), the likely increase in demand as a result of demographic changes alone are expected to cost an additional £448m this year. The report also suggests that councils had planned to reduce spending on adult social care by £700m.

- At the same time workforce pressures in social care are increasing. There are 110,000 vacancies in the sector and a fifth of all workers are aged over 55. Social care is heavily reliant on overseas staff, making it particularly exposed to the potentially detrimental impact of Brexit.

- GPs and primary care - trusts also report that primary care has also become more fragile over the course of the past year. For example, the number of GPs is not rising at anywhere near the rate required to meet the rapidly increasing workload. Nor is it on course to meet the target of 5000 additional GPs by 2021. However, we welcome moves to further extend GP access during evenings and weekends to all areas.