Historic trends in NHS funding – informing the present

In the 2010s the NHS went through the most prolonged financial squeeze in its history. The average annual increase in funding for healthcare between 1949/50 and 2019/20 was 3.7%. However, between 2009/10 and 2019/20, the average real-terms growth in the UK government's health spending was 1.6% - lower than any other decade since the NHS was founded in 1948. This led to growing workforce shortages, under investment in a deteriorating NHS estate and a growing mismatch between the need for greater capacity and changing demand for patient care. It was in this context that the NHS entered the pandemic.

Pressures on the NHS are amplified by the continued financial squeeze on social care and public health services. Funding for local authorities has fallen in real terms by over 50% between 2010/11 and 2020/21, despite a rise in demand for key services such as social care, leaving hundreds of thousands of people with unmet and under met care needs. The lack of a long-term settlement for social care exacerbates pressures on the service, often leaving the NHS, particularly general practice and emergency pathways, as a key source of support for marginalised and vulnerable people.

NHS funding since the pandemic began

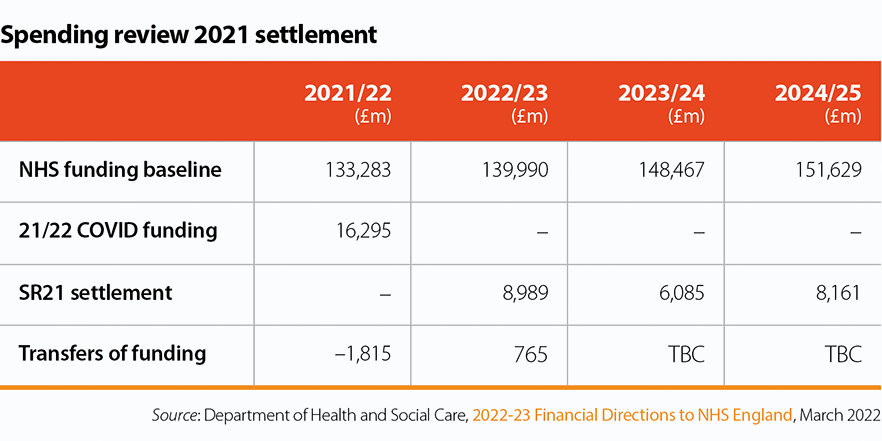

At the beginning of the pandemic, the government made a welcome and much needed commitment to giving the NHS 'whatever it needs' to respond to COVID-19. This led to significant investment in frontline health services in 2020/21.* The October 2021 Spending Review (SR21) later set out a multi-year revenue and capital settlement for the NHS.

*[The King’s Fund illustrates how in 2020/21 an additional £47.1bn of COVID funding – real terms in 2021/22 prices – was spent on top of the Department of Health and Social Care’s core budget of £143.9bn.]

The SR21 funding uplift was generous relative to other public services. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has pointed out, whereas most departments saw significant cuts in core 'day-to-day' revenue spending between 2009/10 and 2021/22, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) budget continued to rise in real terms. However, while any increase in NHS funding will always be welcome, there is still a fundamental mismatch between demand for timely patient care and capacity to deliver.*

*[For example the Health Foundation estimates that by 2030/31, up to an extra 488,000 health care staff would be needed to meet demand pressures and recover from the pandemic – the equivalent of a 40% increase in the workforce, double the growth seen in the last decade]

The impact of inflationary pressures

The impact of inflation is being felt across the economy.* Rising inflation will erode the SR21 cash settlement for public services in real terms. With the revised inflation forecast at Spring Budget 22 (SB22), NHS revenue funding will increase by 3.6% over 2022/23 to 2024/25, slightly less than outlined/envisaged at SR21. At this point it is unclear the extent to which the expected real terms increase in funding for the NHS provided in SR21 will be eroded by inflationary pressures in 2022/23.

*[The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has revised upwards its forecast for growth in CPI and the GDP deflator growth (in market prices) since SR21.]

Efficiency

At the beginning of the pandemic, NHSE helpfully suspended its efficiency requirements of trusts to enable the NHS to focus on the response to the pandemic. However, as the provider sector withdraws from interim COVID-19 arrangements there has been a renewed focus on efficiency and closing the gap between income and expenditure. The government recently announced an initiative to eliminate waste across public services and has doubled the NHS efficiency target to 2.2% a year.* As our survey results show, given current financial and operational pressures, there are a number of factors limiting trusts' ability to recover care backlogs at pace as they want to do, and to close the gap between income and expenditure and deliver efficiency savings.

*[This efficiency assumption has already been baked into ICB allocations, once the 1.1% efficiency factor and convergence adjustment are taken into account.]