The increasing political focus on NHS capital echoed the rising concern among trust leaders about underinvestment, and the growing understanding of the opportunity for improvement and transformation that a new settlement presents.

This section outlines the existing situation trusts currently face, explores its causes and details the impact on frontline services, covering:

- the lack of resource available

- the mismatch between access to funding and the need for investment

- the existing allocation system

- the impact of underinvestment.

To better understand the impact of the capital system as it currently exists on frontline services, we surveyed trusts during July and August 2019, seeking both strategic and technical feedback.

One survey sent to all board members received 200 responses from 143 providers, including acute, specialist, community, mental health and ambulance providers and accounting for 63% of the provider sector.

The other survey, sent to finance directors, received responses from 75 trusts, representing a third of the sector. Again, every type of provider was represented.

These survey responses, plus a set of detailed case studies produced with ten trusts, inform the analysis that follows.

Lack of money available

The most obvious problem facing the NHS relating to capital is that the annual CDEL is not currently high enough, and has not been for the past decade. In its April 2019 report, Failing to capitalise: capital spending in the NHS. The Health Foundation states: "Since 2010/11, capital spending by the DHSC has declined in real terms – from £5.8bn in 2010/11 to £5.3bn in 2017/18, a fall of 7%. This means the capital budget in 2017/18 was 4.2% of total NHS spending, compared with 5% in 2010/11."

These sums include some DHSC capital spending which is not for frontline NHS provision, for example around £1bn of annual research and development spending. Only around 60% of the total DHSC capital spend goes to providers, and this portion has been cut by an even greater amount. The study found that capital spending by NHS providers fell 21% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2017/18, from £3.9bn to £3.1bn (based on 2018/19 prices).

This has partly been brought about by repeated transfers of funding from capital to revenue budgets. The total transferred between 2014/15 and 2018/19 was £4.46bn. A further £471m transfer was made at the beginning of 2019/20 – although this has been mitigated by the £1bn CDEL increase made in the spending round.

At the same time as this prolonged squeeze on capital resources, the main source for large scale health building projects – the private finance initiative – was discredited as delivering poor value for money to the taxpayer. It fell into disuse after 2010 and was finally discontinued in 2018. PFI used to supplement CDEL to provide an extra £1bn of infrastructure investment a year at its peak. As a result of it falling out of favour, very few new or large scale NHS facilities have been built over the past decade.

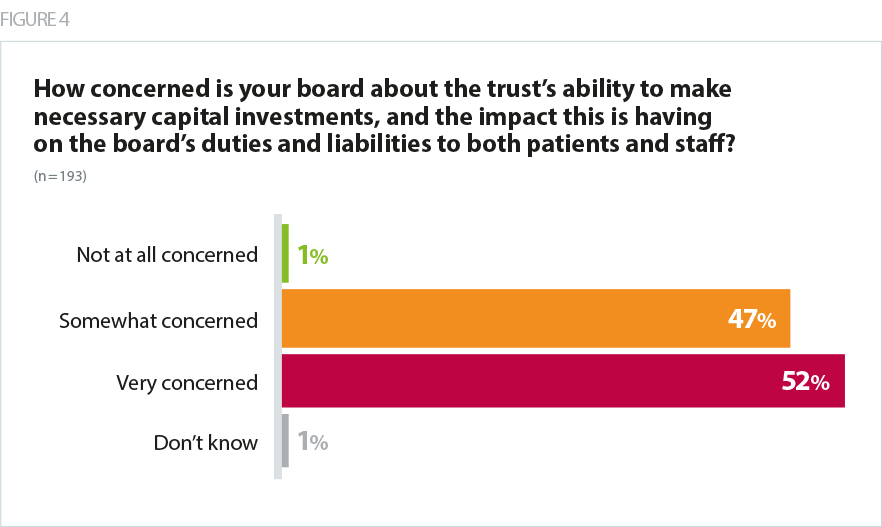

According to our survey, 97% of trust leaders are worried about their organisation’s requirement for capital investment. Of these, 63% were very worried and 34% were somewhat worried. Only 3% were not at all worried.

Meanwhile 74% of respondents did not think they would be in a position to make sufficient capital investment during the coming years.

Our survey of finance directors found that, on average, trusts needed to make £40.2m of capital investments this year across, land and buildings, machinery and fleet, and IT equipment. However, the average likely investment was £24.9m. Asked about the top priorities for a new capital regime, finance directors most frequently named an increase to the national CDEL.

Finance directors overwhelmingly said they would have to defer some of their planned capital expenditure into future years. They said this would lead to delays in new projects starting, delays in replacing medical equipment, making refurbishments and adopting new technology. It may also impact on waiting times or clinical quality.

While these findings date from before the £1bn CDEL increase announced in the spending round, they demonstrate the gap between resource available and investment need which has existed for many years and which is still in need of a long-term resolution.

The mismatch between access and need

Underinvestment in capital was a consequence of prioritising the revenue position, including the introduction of strict control totals for each trust. Alongside these measures, the sustainability and transformation fund (STF) was introduced, later renamed the provider sustainability fund (PSF), to incentivise and support providers to eliminate deficits.

These measures have enabled the DHSC overall to remain within its RDEL in a time of unprecedented rises in activity in NHS services.

However, they have also created an environment in which the availability of capital has not matched the need for investment.

Under STF and PSF, trusts that continued to perform well financially were rewarded with additional payments. Much of this money has gone straight into providers' cash balances, but many have not been able to spend it: NHS trusts are subject to hard capital resource limits, while foundation trusts have also been strongly encouraged by NHS Improvement to constrain capital spending to keep the sector as a whole within its CDEL allocation. However, the implicit agreement has been that those that succeed on the revenue challenge have the reward of investing in facilities in future years.

This combination of factors has caused NHS provider cash balances to rise from £4.17bn in 2016/17 to £5.8bn in 2018/19, even as the cost to bring deteriorating assets back to a suitable working condition, has also risen, from £5.6bn to £6.5bn.

The same factors have also driven a similarly perverse mismatch between the trusts able to generate a surplus to reinvest and those with the greatest need to invest. Trusts struggling with deficits tend to also have difficulty generating sufficient capital funding.

Estates returns information collection (ERIC) data for 2018/19 demonstrates that, for trusts in deficit, the median maintenance backlog as a percentage of turnover was 6.0%. For trusts in surplus, it was 2.9%.

As they are not able to generate a surplus for future reinvestment, trusts in deficit are less able to keep up with growth in their backlog. In 2018/19, spending by trusts in deficit on maintenance equalled 10.4% of the total size of the backlog – for trusts in surplus, the figure was 25%.

Trusts in deficit are more likely to be reliant on emergency capital loans from DHSC to make the investments they need. Although less than half of the provider sector was finished 2018/19 in the red, 51 of the 58 trusts that needed interim capital support loans from DHSC in that year were in deficit. These interest-bearing loans therefore compound the problems these trusts face by introducing additional cost pressures.

How capital funding is allocated

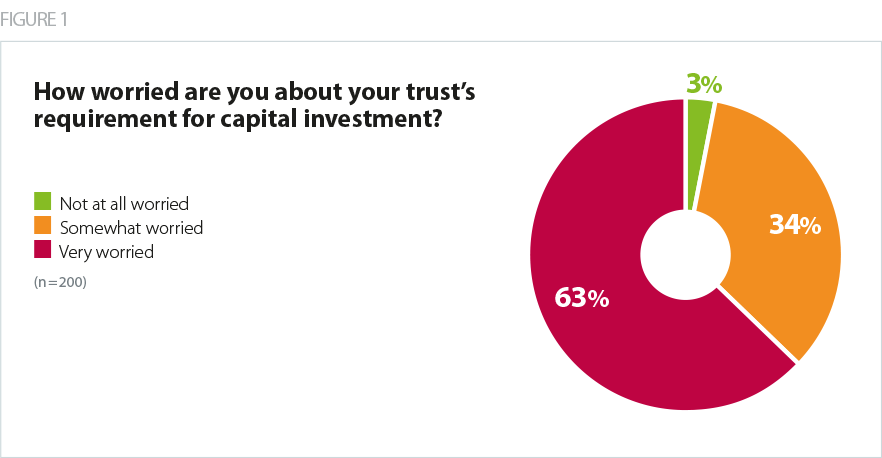

Just 3% of finance directors we surveyed thought the existing capital regime is fit for purpose.

Apart from the insufficient resource in the national CDEL, respondents said the existing system for allocating resources was also inadequate. They said the approval and applications process needed to be clearer and easier, while the "last minute" release of central capital funding during the year makes it hard to spend the money available before year end.

Finance leaders also expressed concern that investment was easier for those that had built up cash reserves via surpluses, rather than allocating based on need.

Where trusts had taken out loans from DHSC, they reported the loan application and approval process is laborious, lacks clarity, and can take as long as a year to be approved.

Broadly trusts were very critical of centrally-run processes for accessing capital, although some acknowledged central bodies such as NHS England and Improvement and DHSC had been helpful given the considerable constraints they faced.

Impact of underinvestment

The impact of trusts' inability to access adequate capital is visible in four ways – in the condition of the estates, patient experience and safety, staff wellbeing and recruitment, and transformation and improvement.

Trust leaders were asked to give detail on assets in 'poor' or 'very poor' condition.

The condition of estates. Overall, 45% of trust leaders surveyed said their trust estate was in poor or very poor condition, compared with 28% who described their condition as 'good' or 'very good'.

This week's joy was the sewage system failing in the main ward block – so far has cost £50k in hiring tankers and drain clearers. Now need to replace the sewage pumps, which wasn’t on the list at all for the year.

Acute Trust

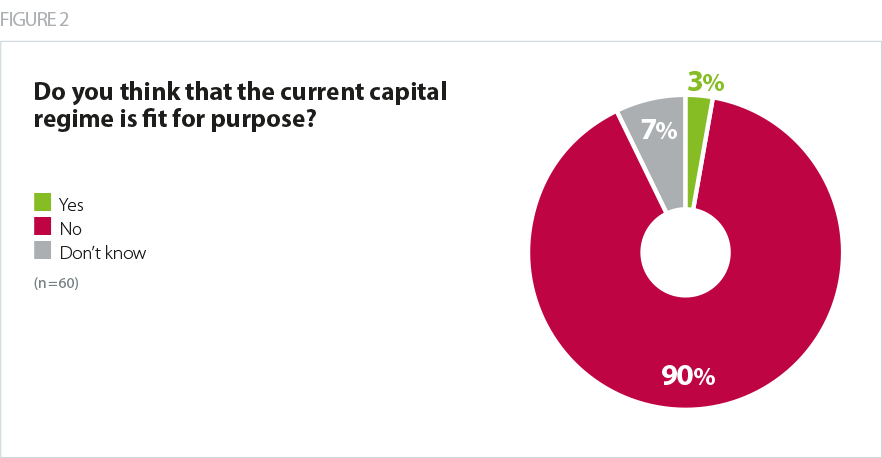

Patient experience and safety. Respondents to our survey were clear that inadequate access to capital has a direct impact on the services their organisations provide. In our survey of all trust board roles, 94% said the current climate of restricted capital funding posed a high (57%) or medium (37%) risk to patient experience, while 82% said there is a high or medium risk to patient safety.

We have two acute hospital sites that still have large dormitory wards... To move to

single, en-suite rooms would mean losing between 30-50% of our beds. There needs to

be a significant national capital investment in mental health bed provision.Combined mental health and community trust

Neo-natal babies will continue to be squeezed into a space that is a quarter

what they need.Acute trust

Staff wellbeing and recruitment. Trusts are also very concerned about the risk of restricted capital on staff wellbeing and recruitment, with 92% indicating the risk is 'high' or 'medium'.

Poor care environments affect the confidence of families and patients, and staff

do not believe they are valued and do not wish to work in poor environments, nor

should they have to. It is an utter contradiction to the stated aim of parity of esteem for mental health.Mental health and learning disability trust

Our estates infrastructure is insufficient to meet the increasing levels of demand we are

seeing. We need facilities to attract, retain and develop staff in a climate of significant

workforce challenges.Acute trust

Transformation and improvement. As well as the impact on staff and patients, the current climate of restricted capital funding is also stopping trusts from improving how they run. 97% reported high or medium risks to transformation programmes, with 95% saying there was a 'high' or 'medium' risk to productivity and efficiency initiatives.

We will be slower in achieving our strategy. We will be slower in achieving integrated

electronic records within our STP. We have prioritised patient safety but integrated

electronic records being delivered over a longer period is heartbreaking to our cause.Combined mental health and community trust

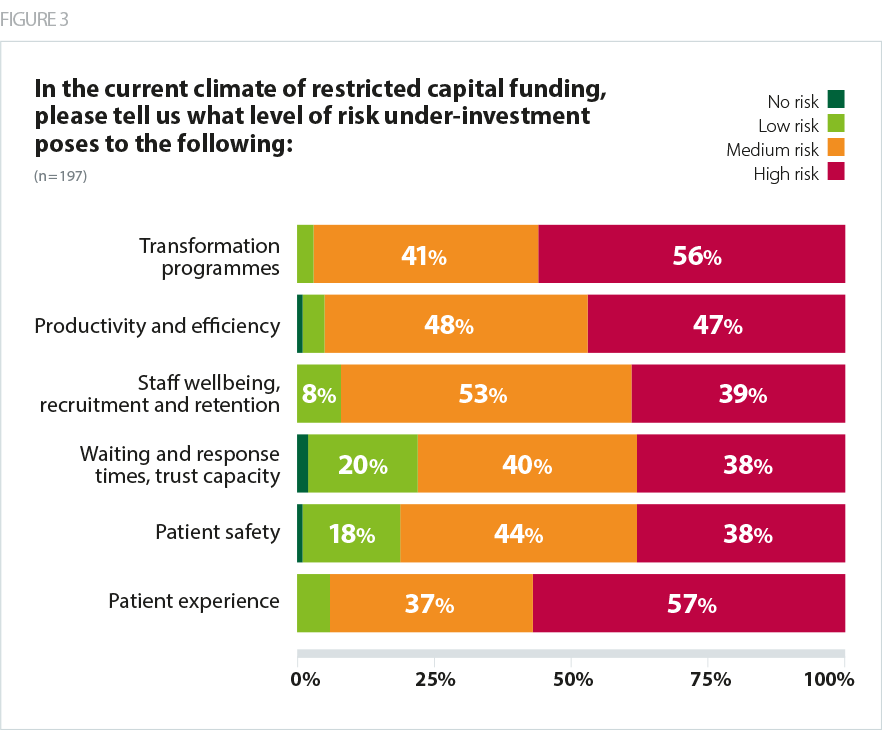

The majority of trust boards are now very concerned about the impact that capital is having on the board’s duties and liabilities to both patients and staff.