[The] high cost improvement target for services may impact upon quality

[It has the] potential to impact quality of care to achieve our CIP target

Patients

The recently published Kirkup review into the failings at Liverpool Community Health Trust has given us an important reminder of the implications of prioritising savings over the quality of care. Its findings showed an explicit focus on delivering cost improvement savings - £30m in five years –had a detrimental impact on staffing levels and the quality of services. The review argues that: "Unless there are exceptional circumstances, an annual cost improvement programme of 4% is generally regarded as the upper end of achievability" (Kirkup, 2018).

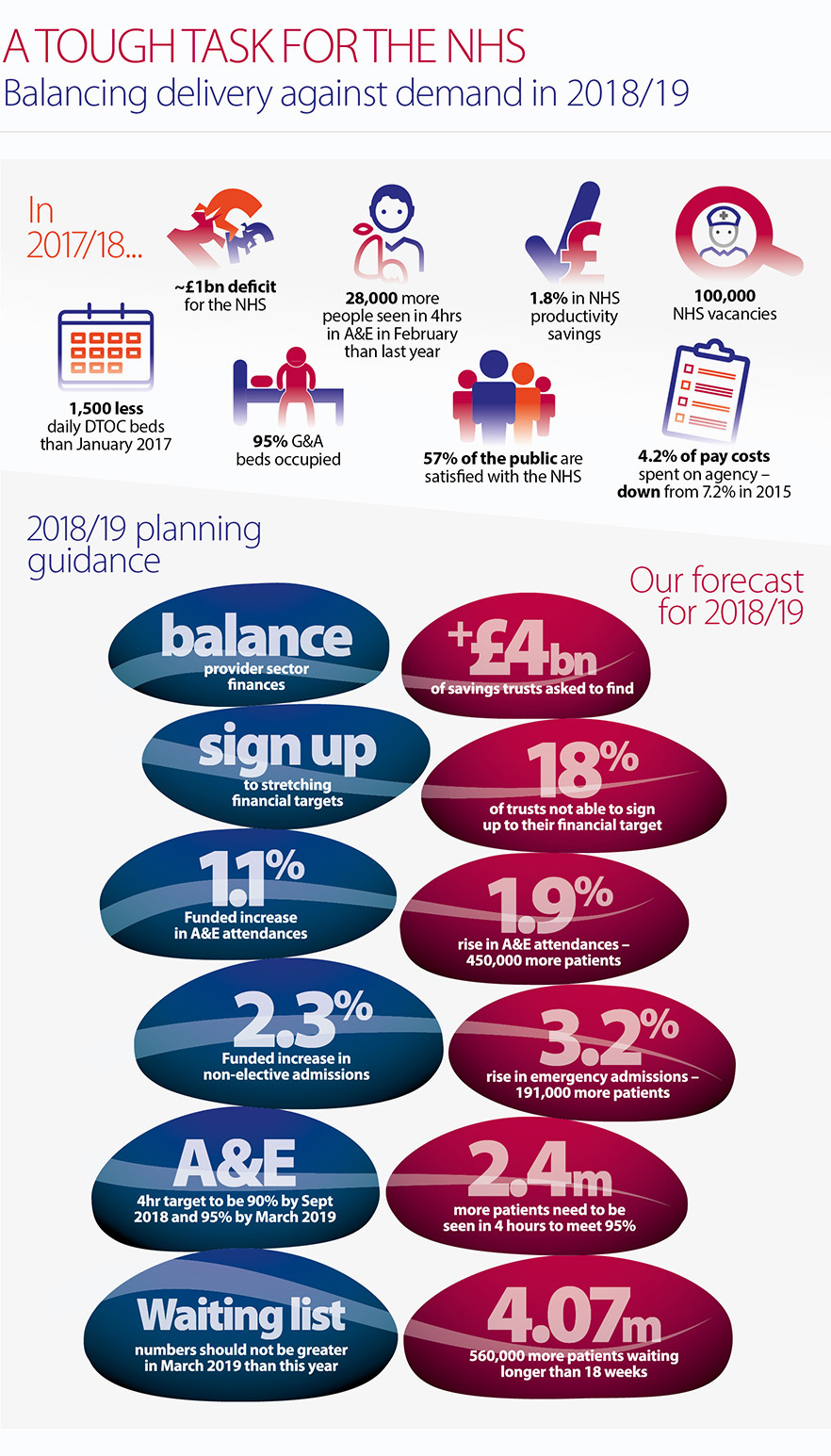

According to our analysis, next year, NHS trusts are being asked to deliver on average 5.7% cost improvement savings, around £4bn across the sector, after several years of delivering 3.5- 4% savings. That is around 20% above what the sector is currently forecasting to deliver (£3.3bn). We know trusts will continue to prioritise patient care and quality and that patient safety is paramount. However, across the NHS, both locally and nationally, we must be vigilant.

There are inherent dangers in putting trusts in a position of delivering savings targets they consider beyond reach, as we have seen in the Kirkup review into Liverpool Community Health Trust and as we saw previously with the Francis report into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust .

This year, the number of patients waiting 12 or more hours on a trolley in A&E, reached 1,043 in December 2017; the highest level since the data collection began in August 2010. In February, the number of mixed sex ward breaches increased to over 2,000, the highest in seven years. Over the winter, one in eight (13%) patients were waiting in ambulances for more than 30 minutes. In this scenario, performance is not just a patient experience issue, it becomes a quality and safety issue too.

There are inherent dangers in putting trusts in a position of delivering savings targets they consider beyond reach

Next year, patients’ experience of care is likely to continue to fall below the standards trusts consider acceptable. In 2018/19, anticipated performance against the two key performance standards, means many patients are likely to have to wait longer for care:

- A&E performance: based on current performance and forecast demand, and assuming no improvement can be achieved, we estimate that in the coming year, over 3.6 million patients will not be treated within four hours, around 68,000 patients more than 2017/18.

- Elective care: based on the trends over the recent years, the size of the elective waiting list at the end of March 2019 will be 4.07 million, above that forecast for March 2018. To meet the 92% standard, we estimate that 3.74 million patients would need to be waiting less than 18 weeks, meaning that almost 155,000 patients will be waiting longer than they should.

National decisions highlight the increasing trade offs between available funding and meeting patients’ expectations:

- prioritising the A&E target means accepting that performance for routine treatment might need to slip as has happened this winter.

- there are now delays and restrictions on the funding of new treatments and interventions. As NHS England highlighted in 2017, the NHS can no longer be expected to implement all new advisory standards from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE): "NICE guidelines can only expect to be implemented locally across the NHS if in future they are accompanied by a clear and agreed affordability and workforce assessment at the time they are drawn up" (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2018).

NHS performance statistics over the last three years show that we have now reached the point where the NHS is no longer able to deliver all that is constitutionally required of it on behalf of patients without significant extra funding and capacity and a means of addressing current workforce shortages.

Staff

The size of increased savings levels required and the need to improve performance and patient throughput to hit the required performance standards in 2018/19 risk adding a significant extra burden onto an already hard pressed workforce.

One of the constants of the last three winters has been the stories of NHS staff going above and beyond to continue to provide care in extremely challenging circumstances. The latest staff survey results depict a worrying state of affairs in terms of the impact of staff engagement and morale across the NHS (NHS Survey Coordination Centre, 2018), which are very likely to continue into 2018/19:

- over half of the workforce (58%) worked additional unpaid hours, a sign of the extra discretionary efforts trusts must make to meet the current level of demand

- over a third (38%) of staff reported feeling unwell due to work related stress in the past 12 months, another symptom of a pressurised workforce

- only around a third (31%) of staff thought their organisation had enough staff to support them to do their job properly

- overall the level of staff engagement has declined, the first time since 2014.

According to research from the King’s Fund in 2017: "The growing gap between demand for services and available resources means that staff are acting as shock absorbers, working longer hours and more intensely to protect patient care…this is particularly worrying given the well-established link between staff wellbeing and the quality of patient care" (King’s Fund, 2017).

This pinpoints the profound implications on staff of continuing to ask them to deliver objectives which we know are undeliverable given the current level of resources. Exacerbated by the intense winter pressures we have seen for over three years in a row, we are now at a point where high levels of staff burnout have been reported.

The additional work carried out by the NHS has only been possible through the dedication of staff. This extra level of discretionary effort cannot be relied on as an ongoing resource, as we argued at the end of last year in our workforce report There for us: a better future for the NHS workforce.

The draft workforce strategy Facing the facts, shaping the future finally sets out the thinking to inform a longer term strategy for the NHS workforce. This is a much needed contribution to considering the future sustainability of the NHS over next decade. However, for 2018/19, it is vital to help frontline organisations retain the workforce they need in the short term. Setting consistently unrealistic performance and financial targets only catches the workforce in a perpetual cycle of failure, further undermining morale and levels of engagement.