The planning guidance for 2018/19 requires the NHS to achieve aggregate performance against the four hour A&E standard of 90% for the month of September 2018, and for the majority of providers to achieve 95% for the month of March 2019. It also states that there cannot be more patients on the elective (RTT) waiting list in March 2019 than in March 2018, and that the number of waits over 52 weeks must be halved. This is, in itself, a further departure from the constitutional standards that reflect safe and high quality care, that people have been told to expect and that trusts want to meet.

In this section, we look at what might happen to the A&E and RTT performance standards in 2018/19. We also look at how the projected growth in patient demand matches the level of activity funded in 2018/19.

Context

As we approach 2018/19, there is insufficient capacity across the health and care system in terms of beds, staff, and different types of services to meet the demand, and increases in demand, trusts are experiencing. As recent performance data has shown, this means that the NHS is now unable to deliver the key constitutional standards.

- Beds. There are not enough beds to meet demand. General and acute bed occupancy had already reached 95% at the end of February, and there were 23% more escalation beds open compared to the same time last year. There is currently no system-wide plan to increase the number of beds across the NHS.

- Staff. By the end of December, one in twelve NHS positions were vacant. This translated to 35,835 nurse vacancies and 9,676 medical vacancies (NHS Improvement, 2018).

- Community services. There is not sufficient community care in place to support patients in out of hospital settings, Furthermore, the number of district nurses has decreased by 41% between November 2010 and November 2017.

- Mental health services. Although mental health funding is now increasing, this is not consistently reaching the frontline, as reported in section A failure to ensure adequate mental health services both undermines quality and safety in these services as well as putting a strain on other parts of the system, in particular the acute and ambulance service. 39% of chief executives and finance directors in our survey were worried about progress being made in implementing the Five year forward view for mental health in 2018/19.

- Ambulance services. The demand for ambulance services over winter 2017/18, combined with the need to implement the ambulance response programme have stretched ambulance services to the limit. As one director of strategy told us: "It is now commonplace over the winter period for A&E corridors to become full of patients and ambulances to queue outside emergency departments. It means that patients in the community could be having heart attacks and strokes when there are no ambulances available to provide an emergency response. The risk of harm is now transferring from those in corridors to patients in the community needing an ambulance" (NHS Providers, 2018).

This highlights that even before we have started 2018/19, the NHS is under substantial pressure, and is facing a significant gap between demand and capacity.

As we approach 2018/19, there is insufficient capacity across the health and care system in terms of beds, staff, and different types of services to meet the demand, and increases in demand, trusts are experiencing.

The prognosis for 2018/19

Demand

The planning guidance suggests funding will grow to accommodate various activity increases expected across the NHS in 2018/19. Our analysis suggests that, based on projecting 2017/18 demand levels forward, these activity levels significantly underestimate the demand the NHS will face and that the service will therefore need to absorb (Table 1).

Table 1: Activity funded in the 2018/19 planning guidance compared to current projections

This gap between demand and funding has, of course, been a consistent story for the NHS in recent years. Advances in clinical practice will only take us some of the way to closing this gap. We also need to create more comprehensive capacity in and outside of hospitals. Without it, additional demand will put further strain on a system which is already pushed to its limits. On current plans the NHS – both commissioners and providers – will need to absorb this additional demand without additional funding.

Our survey findings confirm this. Around two thirds (65%) doubt their sustainability and transformation partnership (or integrated care system) will manage to keep demand within planned levels for A&E attendances. More than half have similar concerns about demand for non-elective admissions and ambulance activity (Figure 1).

It is worrying that more than half of providers are concerned that the central assumptions in the planning guidance around emergency, elective and ambulance demand will not be met. This casts considerable doubt on the ability of providers to meet their performance and financial targets in 2018/19.

Figure 1

The story is different, but equally challenging, for elective demand, where activity levels have actually decreased in 2017/18 (Table 2). Trusts have struggled to fulfil planned-for demand, primarily due to a lack of bed capacity given that emergency care has displaced routine work. As a result, elective income was down 2.5% (£174m) against plan at the end of December 2017.

Table 2: Annual change of elective admissions

As highlighted by Rob Findlay, a waiting times expert, the elective admission rate fell dramatically in January, as trusts responded to peak winter pressures and the decision by the National Emergency Preparedness Panel (NEPP) to stop non-urgent care (Findlay, 2018). In the past two months, the number of elective admissions has fallen significantly, and in January, the admission per working day dropped to 13,400, the lowest January figure on record.

Given the picture for this year, it is inevitable that, without radical changes, trusts will struggle to meet expected levels of demand and deliver on key performance measures.

Given the picture for this year, it is inevitable that, without radical changes, trusts will struggle to meet expected levels of demand and deliver on key performance measures.

A&E performance

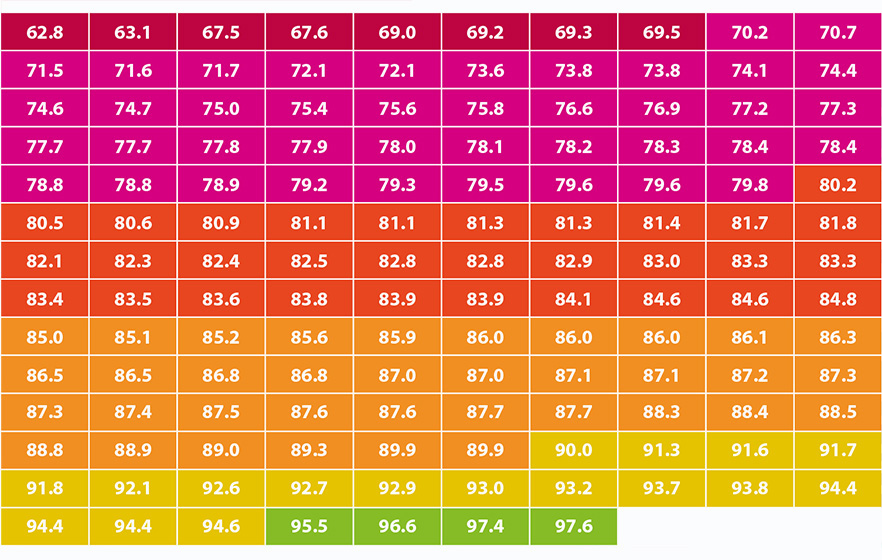

A&E performance is the worst it has been since data collection began in August 2010, with 85% of all attendances being treated and then admitted, discharged or transferred within four hours and 76.9% of patients at major A&E (type 1) departments being treated within four hours. In February 2018, the latest monthly data available, only four major A&E departments met the four-hour standard (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Percentage of all patients seen with four hours at trusts with a major A&E departmen

Our survey data and other evidence shows that it looks impossible for providers to deliver this recovery trajectory in 2018/19 set in the planning guidance:

- Only 5% of trusts responding to our survey indicated that they were confident their STP/ISC could meet the 95% four hour target, a long way short of the 50% plus required by March 2019. 76% were worried or very worried about their STP/ICS’s ability to deliver this performance (Figure 3).

- With current A&E performance at 85%, and with attendances due to increase by 1.9% next year, the NHS would need to treat an extra 2.4 million people within four hours to meet the constitutional target of 95%. That is the equivalent of each trust having to treat an additional 14,000 patients within four hours in 2018/19.

- If the NHS fails to improve performance and it holds at current levels, we estimate over 3.6 million patients will not be treated within four hours in 2018/19.

A&E performance has fallen significantly in each of the last three complete financial years and, although the speed of decline has lessened, there will be a drop in 2017/18 as well, given performance to date.

Accident and emergency performance is the worst it has been since data collection began in August 2010, with 85% of all attendances being treated and then admitted, discharged or transferred within four hours.

In this context, the scale of improvement required to deliver the recovery trajectory in the planning guidance looks far too optimistic. For example, an analysis of the improvement needed in the 137 major A&E departments featured in Figure 2 above suggests that, for a majority of these departments to deliver 95% by March 2019 as required, assuming those current closest are most likely to hit the target:

- 17 trusts (12%) would need to improve their performance by up to 5% compared to their February 2018 performance

- 36 trusts (26%) would need to improve their performance by up to 10%

- And a further 12 trusts (9%) would need to improve by more than 10%.

While a small number of trusts have improved their performance year on year, there is nothing to suggest that this scale or width of improvement is deliverable without a major system change, such as a very large jump in capacity, funding or staffing levels, none of which are envisaged in the planning guidance.

Figure 3

Elective waiting time performance

Performance against the 18 week waiting time target has fallen to its lowest point since March 2009 although the vast majority of patients (88.2%) are still being seen within 18 weeks (Figure 4).

Figure 4

When we factor in non-reporting trusts, the size of the waiting list is nearly back to around 4 million patients (Findlay, 2018), the size it was in 2007 when reporting first began. Performance against the target now sits at 87.9% and we have used this figure for the subsequent analysis.

The planning guidance states that there cannot be more patients on the waiting list in March 2019 than in March 2018. It also suggests that the number of waits over 52 weeks must be halved.

Again, our analysis, which factors in non-reporting trusts, shows that providers will struggle to stabilise elective performance next year:

- Based on the trends over the past few years the size of the elective surgery waiting list will reach 4.07 million by the end of March 2019. Unless performance improves this would be greater than forecast for March 2018.

- Extrapolating 2018/19 performance from current trends, based on the increasing size of the waiting list, 3.58 million patients will be treated within the 18-week standard, meaning that 492,500 patients would be waiting over 18 weeks for treatment - 10,000 more than we have at the moment.

- But even this seems optimistic, and would require performance to hold at current levels. In fact, since January 2014 performance against the standard has fallen by between 1.5% and 2% each year. If performance were to slip by 1.75%, the standard would drop to 86.2% which could mean that the number of people waiting more than 18 weeks could increase to 560,000 by March 2019, over 79,000 more than at the moment.

- By January 2018, the number of one-year waiters rose to above 2,000 (if non-reporting trusts are factored in), the highest since 2012. Although tackling this is a priority for the provider sector for 2018/19, achieving it will be challenging.

This is further confirmed by our survey results. Only 14% of trusts responding to our survey indicated that they were confident their STP/ICS would be able to keep the number of patients on the waiting list stable. Over half (55%) were worried about their STP’s/ICS’ ability to meet this target locally (Figure 5).

Figure 5

The planning guidance envisages an increase in elective activity of 4.9% for outpatient attendances and 3.6% for elective admissions as the level of activity required to meet the target of holding list size and halve the number of long waiters.

But this takes no account of the constraints trusts will face in delivering these increases. These are:

- Elective work has been displaced by emergency work throughout 2017/18 and there is no reason to believe this will change in 2018/19 - at the moment, there are no comprehensive plans in place to significantly increase available emergency capacity during 2018/19.

- Trusts report that they face physical space constraints in expanding their elective capacity to the extent required.

- Trusts report that they face major constraints in recruiting the staff required to deliver this scale of increase.

As outlined above, due to the way these constraints operated in 2017/18, elective activity has actually fallen by 1.5% so far this year. There is nothing to suggest that trusts can reverse this trend to the extent of delivering a 4.9% increase in outpatient attendance and 3.6% in elective admissions. Trust chief executives suggest they will do well to deliver the same amount of elective activity in 218/19 as they did in 2017/18.

Turning around the current performance against the constitutional standards will be a top priority for trusts in 2018/19, and recovering A&E performance to unlock additional funding will be central to planning for acute services. But the gap between planned and actual growth in demand cannot continue to widen as it leaves both providers and commissioners in the cycle of having to absorb the financial burden associated with unrealistic assumptions. We explore what we need to do in response to this in section 5.