Trusts describe their role in tackling health inequalities as critical, both in terms of the services they provide and their role in the wider system. Many are sharing a vision to be fully embedded within the system-wide response to health inequalities and the wider determinants of health, and are determined to maintain momentum and concerted action to achieve real change rather than health inequalities being a short term 'buzzword' that loses focus after a period of time.

Need to recognise that inclusion is a behaviour and not a project.

Chair

Working across the system on the agreed priority areas. Creating the conditions where we can commit to making a difference in this area.

Chief Executive

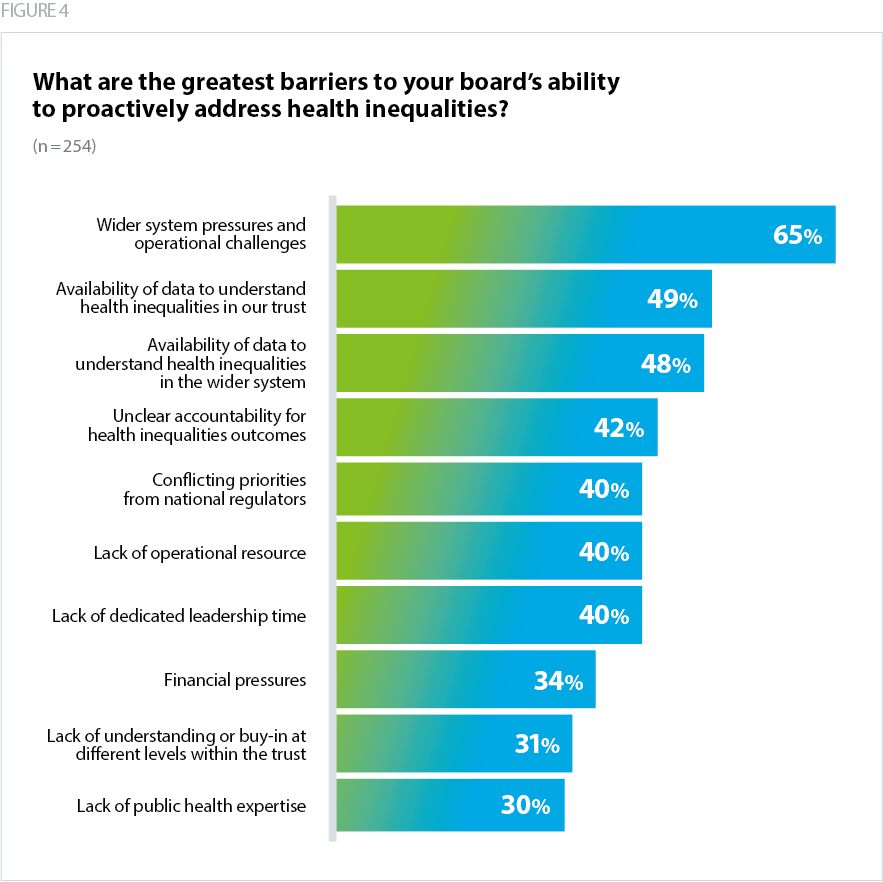

We asked trusts to describe the barriers to proactively addressing health inequalities as a board. There are a number of factors that trust leaders feel present an obstacle to their board's progress on tackling health inequalities (Figure 3). We also asked trusts to describe enablers, and found that the majority of these barriers, when addressed, subsequently become enablers.

System pressures and operational and financial challenges

Nearly two in three (65%) respondents named wider system pressures and operational challenges as a barrier to progress. A higher number of acute specialist trusts (80%) and a smaller number of mental health/learning disability trusts (52%) named this as a barrier.

Trusts responded to this survey at the beginning of the most recent winter COVID-19 wave, with rising admissions against a backdrop of unseasonably high levels of emergency care demand, a significant and rising care backlog, and with pressures seen across acute, elective, community and mental health services. Throughout the pandemic it has been necessary for trust boards to focus on immediate operational pressures, patient safety and quality of care. Wider system pressures also refer to the broader context trusts are operating within, including increased socioeconomic inequality and the complexity of system transformation and work to develop ICSs further.

This may explain why, although two thirds named wider system pressures as a barrier, fewer (40%) said that a lack of operational resource and ability to dedicate leadership time to this issue was a challenge, and despite the complexity of balancing health inequalities improvement with the range of additional pressures, trusts are clearly committed to devoting resource and time to this agenda despite the pressures they are facing.

Just over a third (34%) cited financial pressures as a barrier to progressing health inequalities within their organisation (Figure 3). Trusts have expressed a need for funding arrangements to more explicitly take into account the specific challenges health inequalities bring, and trust leaders say that additional funding to tackle health inequalities should be proportionate to the scale of the challenge and the proportion of the local population facing health inequalities.

Post COVID-19 we need to look at three or four key priorities and be willing to shift resources as part of a serious attempt to reduce inequality and improve population health.

Chair

Comments also revealed the tensions in how trust leaders strive to address health inequalities within the wider context, such as challenges in securing agreement about how best to allocate funding and resources according to the greatest health inequalities challenges.

Resistance to reallocate resource within the system where [there are fewer] health inequalities.

Chair

The combination of capacity issues and operational and financial challenges, alongside variation in how well systems are collaborating towards a mutual response to tackling health inequalities, creates a complex environment within which trusts need to drive their progress.

We want to have this front and centre, but limited leadership capacity, and probably not engaged enough in system work. Hope to see this expand in the coming years, seen as a priority for the board.

Non-executive Director

Data availability

Only by developing a shared understanding of the health inequalities faced by people in their local communities and using their services, can boards be sure the work they do to address such inequalities will have the desired effect. For example, trusts describe the importance of having complete data on patients' ethnicity, to ensure analysis is accurate and does not contain gaps. The story the data tells is a key enabler of productive, ambitious conversations at board level about how to challenge unjustifiable differences in access, experience and outcomes, and embed effective assurance and challenge on work to address them.

However, despite the clear importance of data and analysis, around half of respondents named the availability of data to understand health inequalities within the trust and in the wider system as a barrier to progress (Figure 3). Across sectors, a greater proportion of acute and mental health trusts named the availability of data to understand health inequalities in their trust as a barrier (53% and 63% respectively), while fewer community trusts named this as a challenge (43%) compared to the average.

For many trusts, data has been a key enabler of progress. Some describe how access to real-time data during the pandemic has helped prioritise action and provided a clearer perspective on inequalities, but affordability and cross-system working including cross-border and cross-sector data sharing are still challenges. Population health management is likely to form a key component of trusts’ activity in place-based partnerships, and support to underpin joint work to reduce health inequalities with clear, usable data, will be key as systems develop further.

…Information from local authority and real time data used throughout the pandemic enabled a much clearer perspective on inequalities; keen to see the continued value of this…

Chair

Some trusts highlighted challenges around the complexity of data as a barrier to progress, as analysis requires additional capacity and resource to carry out. Trust leaders have told us that access to disaggregated data on deprivation and ethnicity and support to analyse this data effectively would better equip them to address health inequalities within their trust and wider system. One trust leader noted the importance of being able to access reliable and accurate data without the need for complex analysis as an enabler to reducing health inequalities.

Access to good quality, accurate data that highlights problem areas without lots of detailed analysis.

Non-Executive Director

Giving access to data and analysis of that data, with presentation of it in an easy to digest form so the priority areas really stand out.

Non-executive Director

Analytics! This is a really complex area fraught with interpretive difficulties.

Chief Executive

There are then questions around how trusts then use their data to develop a shared understanding of 'what good looks like' for people from marginalised communities, and how best to ensure a culture of equity is built into services. Some trusts have described appointing dedicated public health expertise, such as a public health consultant, as an enabler of more sophisticated data analysis to inform board level action and support them to develop that shared understanding. Others have established board-level expertise through their non-executive director (NED) community. Despite this, a third of respondents (30%) cited a lack of public health expertise as a barrier to progress (Figure 3).

Good public health expertise – we have employed a public health consultant with an interest in mental health as associate medical director.

We have appointed public health consultant into our senior board level strategy and planning role – has shifted board mindsets and approach.

Chief Executive

We have a national expert on health inequalities as a NED on our board. His wider insights have been influential on the trust and in the wider system.

Chair

Accountability and conflicting priorities

Just under half of respondents (42%) listed unclear accountability for outcomes on health inequalities as a barrier to progress, and 40% cited conflicting priorities from national regulators as an issue for their trust (Figure 3). Trust leaders have described the challenge of prioritising health inequalities at board level, as it was not historically embedded as part of a trust’s 'core busines' and does not consistently align with assessments undertaken by national regulators.

For example, many services are assessed primarily against broad access targets such as the 18 week elective waiting time target or ambulance blue light response times. Trusts have historically been encouraged to focus on and prioritise aggregate operational measures rather than drill down into variation between specific groups. Trusts are keen to work towards an operating model and supportive regulatory framework which enables them to meet these requirements while taking a health inequalities improvement approach.

Work is underway to put in place systems of accountability for progressing health inequalities, but these are still emerging and developing in response to new national priorities and legal duties due to be implemented this year as part of the health and care bill. The national bodies have started to consider how best to ensure accountability for health inequalities facilitates progress and meaningful action. However there is still work to do to ensure this translates clearly for trusts and systems, so the raft of asks from the centre are aligned with local objectives, the reality of delivering equitable services for diverse populations, and the complexity of measuring outcomes.

Better clarity on role of system vs place vs provider on tackling health inequalities. For example, organ donation is run from the organ donation committee in acute trusts. Other population health issues run from the CCG (soon to be ICS). What is the right model, with clearer roles and responsibilities? Better data/approach to data advice too.

Non-Executive Director

Trusts need an enabling regulatory environment to meet their objectives to reduce health inequalities, and to effectively work with their system partners to improve outcomes across the wider determinants of health. To cement a long-term commitment to improving health inequalities as part of their 'day-to-day business', trusts will need a supportive infrastructure which rewards progress on health inequalities as a measure of good operational and financial performance.

A lack of prioritisation by regulators [is a barrier].

Chair

Look forward to the new [Office for Health Improvement and Disparities] supporting and challenging us to achieve so much more. Getting it on the radar across all the regulators so we can make sure we have joint agenda and approaches and supported on this as vigorously as we are on performance in other areas.

Chief Executive

While there is a stronger emphasis and renewed focus from NHS England and NHS Improvement and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) to address health inequalities, there is still potential for the regulators to embed health inequalities improvement as part of their definitions of quality, safety and performance, rather than as a separate initiative to assess trusts on.

This needs to be explicitly built into system and provider performance – no 'good' or 'outstanding' without having credible plans that are being implemented.

Chair

Securing buy-in at all levels

Trust leaders described the value of embedding health inequalities improvement into the wider organisational culture. As a microcosm of the community at large, staff working at all levels of trusts, from the frontline to senior levels, can contribute their insight, understanding and lived experience of health inequalities to support improvements to services.

A significant proportion of trusts said a lack of understanding or buy-in at different levels within the trust was a barrier (Figure 3), and this poses a definite challenge for the sector. Trusts have shared examples of work they have done to encourage buy-in from staff including listening events, developing a more diverse board, and building in ways of listening to and acting upon people’s lived experiences. There is variation across sectors: while 40% of acute specialist trusts described this factor as a barrier to progress, just 14% of community trusts and 26% of mental health and learning disability trusts said the same.

Trusts have identified in-depth, bottom-up discussions with staff and communities as an enabler of progress because they help demonstrate health inequalities improvement as tangible, with real world impacts. They are keen to further embed these types of discussions into their ways of working as they progress work on health inequalities. Some trust leaders are recognising the community leadership roles their staff working in more junior posts may be carrying out, and listening to their experiences and insights to support work to reach into communities which are underserved or struggle to access services.

General discussions encouraged in this area. It has also come up either directly or indirectly from patient stories at public board meetings.

Non-Executive Director

Working hard to develop a diverse board. Stopped hiding behind averages and disaggregate data. Listen with humility and try and ensure that in asking people to share their stories they are not further damaged.

Chair

Trusts also highlighted the importance of ensuring all parties have access to the data so clinical teams can have ownership over the work to make their services more equitable. They also describe a need for compassionate conversations about how to address structural issues that are present within the trust, in ways which avoid placing the blame for inequity but rather enable clinicians to work together to design solutions which improve access and narrow health inequalities where they can be found.

Help and support not beat up. Share good examples and facilitate good conversations that enable buy-in from our communities – this can't just be about NHS imposing it on all.

Chief People Officer

One trust leader described the challenge of assuaging clinicians' concerns about altering pathways for different ethnicities, with a prevailing assumption that the process needs to be the same for everyone rather than trying to ensure the outcome is the same for everyone. This highlights the role trust boards play in developing that shared understanding of 'what good looks like' for people from marginalised communities, and building a culture of equity which recognises that to achieve the same outcome, some people need different routes to access services.

Clinical concerns about having different pathways for different ethnicities i.e. an assumption that the process has to be the same for everyone rather than trying to ensure the outcome is the same for everyone.

Chair

System-wide collaboration

Health inequalities do not begin or end with individual trusts, or indeed with healthcare more widely. Trusts recognise that they will lead much of the work to address healthcare inequalities, and have a key role to play in influencing improvements in how well services meet the needs of diverse communities. However addressing the broader health inequalities people face as a result of the wider determinants of health such as housing, employment, poverty, as well as the structural inequalities people from ethnic minority backgrounds face, will require a system-wide effort.

Trusts are therefore working collaboratively to tackle health inequalities with other trusts, primary care, local government and the voluntary sector. Much of this collaboration is taking place in provider collaboratives and place-based partnerships supporting key partners such as public health teams in local authorities. This partnership approach fosters a more detailed understanding of the needs of the population, by linking the different but equally important contributions different system partners make. Trusts recognise that, given the wider determinants of health, and the multitude of partners within a system contributing to access and outcomes, they can only move the dial on health inequalities through a whole-system approach.

Working at place and system level with key partners such as public health.

Non-Executive Director

There is a need to a much more integrated approach to local performance measures that reflect the impact of integrating service deliver in better ways.

Chair

The operational context may mean trusts need to draw on the community links that their system partners have, to identify how best they can contribute to a unified approach to reducing health inequalities. These trusts recognise the assets that their partners can offer in terms of a deep understanding of local communities' needs, access to datasets, and a more holistic approach to the wider determinants of health.

As an acute trust we need to work closely with ICS partners.

Non-Executive Director

Provider Collaborative working even before COVID-19 and the move to an ICS. As an acute trust we have no choice but to work with our partners in our patch in a way that improves patient outcomes.

Non-Executive Director

While the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated collaboration, many trusts have a significant history of collaboration and integration with local partners, with strong relationships at a local level enabling productive conversations about how best to drive work on health inequalities forward. Despite this, some trusts expressed a view that systems now need to collectively move beyond talking about health inequalities and use these wider forums for action.

It must be and will be hard wired into system priorities within each ICS ....so very important.

Non-Executive Director

This needs to be a high priority for the system and continue to be so. All partners within the system need to understand their role and how we can work together to make the most lasting and sustainable impact.

Chief Executive

While relationships are a key enabler of meaningful collaborative work on health inequalities, managing competing priorities can be a significant challenge, and establishing a shared vision on health inequalities between partners, with an enabling regulatory framework, will be crucial. There is a need to make sure all aspects of the system are 'speaking the same language' and to bridge the cultural gaps across different parts of the NHS, social care services and local government, who may all be talking about health inequalities in different ways. Trust leaders say this should be supported by national and regional leadership to drive real change beyond strategic planning and objective-setting.

I think there needs to be greater directional leadership to encourage health and social care to work together on this – the answer will only ever be through collaboration, shared ambition and joint working. At the moment, I do not see enough direction to force development of the required agenda. ICS leads should be required to develop the strategic plans to deliver initiatives that tackle inequalities and deliver improved outcomes.

Chair