Having enough staff with the right skills and values is a fundamental strategic issue for the provider trust sector. In a recent survey, two thirds (66%) of trust chairs and chief executives told us workforce is the most pressing challenge to delivering high-quality healthcare at their trust.

Generally, the most difficult shortages are of clinical staff, though there are significant challenges in respect of the wider workforce too.

Medical staff shortfalls

While it is widely accepted that the NHS faces shortages of clinical staff, there is no definitive measure of its scale. Authoritative, public, timely data on vacancy rates for clinical staff at a national level is still widely unavailable. In addition, there is a lack of insight into regional variation and differences between different staff groups.

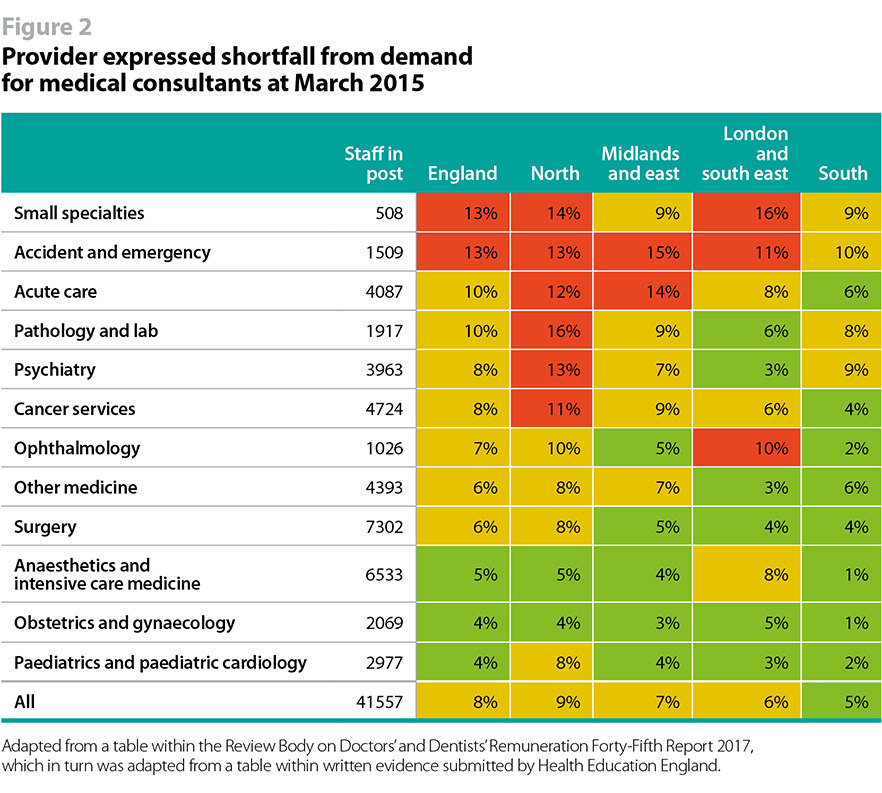

The medical consultant shortfall rates summarised in figure 2 show variation by medical specialty and region. (We have made use of the shortfall rates provided by Health Education England to the NHS pay review bodies for their 2017/18 reports. This is far from ideal as the rates are more than two years old. However, it is the most comprehensive authoritative data we are aware of and also provides limited breakdown by staff groups and the four NHS regions.)

Shortfalls of 6% or less are coloured green, shortfalls of between 6% and 10% are coloured amber and those of 10% or more are red (there are some exceptions to this which are due to the rounding up or down of numbers). (Health Education England explain that green does not mean that a shortfall is not a problem for providers. It recognises an element of ‘labour market friction’ is to be expected as staff leave and are recruited. It should also be noted that March is the point in the year when shortfall rates are likely to be highest.)

It is clear that the north and, to a lesser extent, east and midlands, are generally faced with higher shortfalls than London and the south east and the south. There are well known shortfalls of accident and emergency consultants across all regions of the country and, outside of London, shortfalls in psychiatry. Notable shortfalls are also found in acute care, pathology, cancer services, ophthalmology, and within the small specialties taken as a whole.

Similar regional and specialty patterns can be seen in recent analysis by the British Medical Association of specialty training fill rates.

The NHS national bodies have published an emergency care workforce plan (NHS Improvement), together with the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, which mainly focuses on growing the emergency medicine workforce over the next two years and beyond, and a mental health workforce plan (Health Education England), which aims to grow the mental health workforce, including psychiatrists, by 2021[3]. The government has also announced an expansion of medical school places – 500 extra places from 2018 and an additional 1000 more from 2019 – with the aim of making the NHS ‘self-sufficient’ in terms of doctors. It will be six or seven years before these extra medical students start to graduate.

Other clinical staff shortfalls

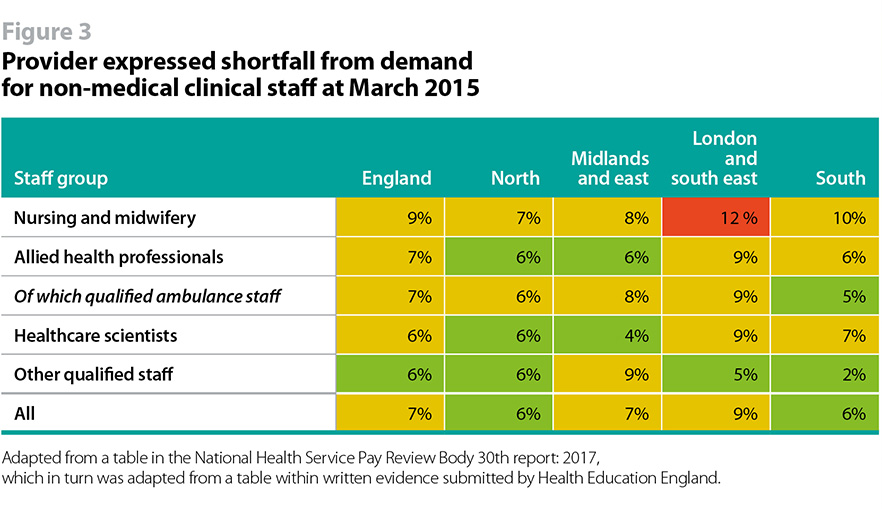

The shortfall rates for other clinical staff summarised in figure 3 also show variation by staff group and region.

There are shortfalls of nurses, allied health professionals such as radiographers and occupational therapists, paramedics, and healthcare scientists. Inevitably the aggregate nature of these figures hides specific shortages of some staff such as psychologists in mental health services.

London and the south east has the highest shortfalls across all staff groups except in the category of other qualified staff. Trusts in and around the capital tell us that the high cost of living, particularly housing, is a barrier to recruiting and retaining staff and that the current high cost area supplements do not adequately mitigate it.

London and the south east, closely followed by the south, also has a particularly high shortfall of nurses, although the north and the midlands and east are experiencing notable shortfalls too. As the shortfall rate data is more than two years old it probably understates the current nursing shortfall; the Royal College of Nursing’s latest estimate is that there is a shortage of 40,000 nurses across England. This severe mismatch of supply and demand of nurses can be explained by rising demand for services and a greater focus on safety and staffing levels resulting in greater demand for nurses from trusts (NHS Improvement).

Worryingly, analysis by The King’s Fund shows that the number of nurses working in the NHS in England has begun to fall for the first time in three years. There are also specific concerns about community, learning disability, and mental health nursing, where falls in staff numbers and high shortfalls are masked by the overall numbers (the fall, since 2012, in the number of community (-5%), learning disability (-24%), and mental health (-8%) nurses can be seen in NHS Digital’s NHS workforce statistics July 2017 provisional statistics: The nursing shortfall is now the focus of an inquiry by the health select committee.

Following the government’s reform of healthcare education funding, nursing and other clinical students now fund their own education through the student loan system. This means that in principle there is no cap on the number of students who can be educated, whereas in the past the number of students was capped at the number of bursaries for which the government made funding available. However, in practice, healthcare students will require clinical placements at provider trusts and so the number of students is limited by the number of clinical placements that trusts have capacity and funding to deliver.

Also, any extra healthcare student places that are offered can only be filled if enough students of the right quality and with the right values can be attracted to apply to courses. As part of its reforms, the government has committed to 10,000 more healthcare students by 2020. There are particular concerns from trusts about the viability of some learning disability nursing courses where students have tended to be more mature and may be more likely to be discouraged by needing to take out a student loan.

The government has also recently announced funding for a 25% increase in nursing clinical placements, to support a 25% increase in nursing students (just over 5000 more), from 2018. This is welcome, but there is much work for trusts and higher education institutions, with national level support, to do if the extra clinical placement capacity is to be realised and sufficient people are to be attracted to apply for and take up the extra nursing student places (Department of Health). There are other routes into nursing. A small number of new nursing apprenticeships (less than 50) are beginning in 2017 with more to come in 2018. Postgraduate nursing diplomas are another route but funding arrangements for these courses from 2018 are still to be confirmed, making it difficult for higher education institutions to attract students.

While these initiatives are welcome, it remains far from clear that they will together add up to the answer to the current staffing shortfalls. In addition they will take time to boost the domestic supply of staff – for example nursing degrees take three years and nursing apprenticeships take four years – and so it is essential that the NHS is able to continue to recruit staff from outside the UK for the foreseeable future to mitigate the workforce gap.

Wider NHS workforce

The wider NHS workforce makes an invaluable contribution in supporting the delivery of patient care. They work in a great variety of roles such as security, healthcare support, estates, porters, and administrators at various levels.

There are no national shortfall rates available for other NHS staff, but trusts tell us that for particular roles it is difficult to recruit and retain sufficient staff, for example in IT, estates, and clinical coder roles, and again there is of course variation in particular regions of England. There are skills shortages.

As a report by the Health Service Journal highlighted last year, there is much more to be done to support and promote the wider NHS workforce staff.

Comparing workforce growth and demand growth

When considering whether the NHS has enough clinical staff, what is key is not whether there are more or less staff today than there were in the past, but rather whether we have the number of staff with the skills and values we need to meet the level of demand for services and expectations of quality we face today and expect to face in the future.

Figure 4 uses indexing with 2013/14 as the baseline year to illustrate that almost all demand metrics across the hospital, mental health and ambulance sectors (we do not have demand metrics for the community sector) have grown more quickly than the workforce has grown in the last four years.cccccccccccccccccccccccc

Figure

The NHS has more clinical staff, overall, than ever before. Since 2010 there has been an increase in the number of staff (The King's Fund) in all groups except managers and backroom support staff. But the fact is, as figure 4 illustrates, staff numbers have not kept pace with rising demand for services. Increased patient acuity is also a factor. And, crucially, following high-profile failures of care there has been a push for higher staffing levels and a corresponding regulatory focus and rapid rise in demand for nurses from provider trusts (NHS Improvement).

International supply and Brexit

Faced with the current workforce gap, and in the absence of domestic supply quick fixes, there is a continued need for the NHS to recruit from the EU and the rest of the world to mitigate clinical staff shortfalls. 85% of trust chairs and chief executives told us that it will be very important or important for their trust to recruit from outside the UK over the next three years.

Yet the outlook for international recruitment by provider trusts is uncertain. When asked for the biggest challenge to recruitment of non-UK staff for their trust, 38% of chairs and chief executives cited uncertainty linked to Brexit as the biggest barrier, 32% pointed to professional regulatory requirements, including language testing, and 16% suggested current immigration policy and charges.

The NHS has one of the highest levels of reliance on overseas staff in the OECD. Around 29% of doctors and 13% of nurses in the UK were trained in another country, compared to OECD averages of 17% and 6%. The UK has greater reliance on both doctors and nurses trained overseas (The Health Foundation) than Germany, France, Spain, Canada, and the USA.

These staff make a vital contribution of delivering NHS services. Some 12.5% (138,000) of NHS staff in England are non-British nationals, and 5.6% (62,000) are from the EU (House of Commons Library). Social care also depends on a big contribution from non-British staff (Skills for Care), with 7% of workers (95,000) from the EU and 9% (125,000) from the rest of the world.

Again, in the NHS, the picture varies (House of Commons Library) by staff group, between trusts, and across regions of England – for example in London around 12% of staff are from the EU, whereas in the north east it is around 2%.

Clearly, it is essential that people from the EU already working in the NHS have certainty over their right to remain and a straightforward process for establishing that right as soon as possible. All the indications from the government, not least the secretary of state for health (the Telegraph), is that this is what they want, but until it is finally confirmed, the uncertainty and anxiety for EU staff will inevitably continue.

As one trust leader put it: “We would not be able to maintain high-quality care for the people we serve without our diverse workforce. The current lack of progress in the Brexit negotiations is creating unhelpful uncertainty in an already challenging workforce environment”

Until such a time as the NHS has significantly increased the numbers of clinical staff trained domestically and successfully recruited and retained them within the NHS, then any significant reduction in the number of staff from overseas is likely to have a serious adverse impact on service availability and quality. The pipeline of international staff must remain open.

At present, individual provider trusts undertake their own campaigns to recruit staff from overseas. While some may want to continue to do so, the time seems right for a sector-wide international recruitment programme to be created which trusts can pay to opt into if they wish. There may be economies of scale and opportunities to better support non-UK staff to meet professional regulatory requirements.

Language requirements for professional registration for nurses from outside the UK

The introduction of a new language requirement in January 2016 has affected the number of EU nurses working in the NHS. The number of nurses from the EU registering to work in the UK has dropped by 96% in less than a year. In July 2016, 1,304 EU nurses came to work in the UK; this fell to 46 in April 2017 (The Health Foundation). While this was widely linked in the media to the Brexit vote, provider trusts tell us that the introduction of a language requirement for EU nurses was by far the largest contributing factor to the fall. Trusts are concerned that the language requirement has been set in a way that has acted as a barrier to recruitment (this has been the situation for some time in the case of international applicants and latterly for EU applicants as well). We welcome the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) current review of its approach in this area, its engagement with provider trusts, and are working closely with the regulator to feed in provider perspectives and evidence. Positive changes have already been made (NMC). Careful consideration needs to be given to guaranteeing patient safety, which was the reason language tests were introduced, and the patient safety implications of not being able to fill high-vacancy rates with high quality nurses from abroad. We urge the NMC to continue the review at pace.

Supply – what needs to happen

The government should:

- urgently confirm the right to remain for the 60,000 EU staff working in the NHS and provide a straightforward and inexpensive way for them to establish this right;

- commit to a future immigration policy supporting trusts to recruit and retain staff from around the world to fill posts that cannot be filled by the domestic workforce in the short to medium term.

The Department of Health and the NHS national bodies should:

- work with trusts, higher education institutions, and unions, providing strategic leadership, to ensure the intended 25% increase of nursing students from 2018 is delivered and any risks to application rates or the number of places set to be offered are identified, monitored, and addressed as required. The experience of 2017 has shown we cannot just assume an announced expansion of students will actually happen;

- work with trusts to develop an international recruitment programme that trusts can choose to pay to opt into, rather than undertaking their own individual recruitment campaigns. The Global Health Exchange Earn, learn, and return pilot programme is a sensible place to start and could be run on an indefinite basis, positioning the NHS in England as a global centre of excellence for healthcare education.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council should:

- continue to progress at pace its review of language requirements for the registration of non-UK nurses, maintaining patient safety and engaging with provider trusts and other stakeholders.