Today saw the publication of a number of key NHS datasets, including the monthly NHS England activity and performance statistics, the monthly NHS England COVID-19 hospital report, as well as week 10 of the winter sitreps from NHS England and NHS Improvement. The pressure on the NHS across January has been enormous, and while we are now coming down from the various peaks of COVID-19 demand experienced in the current wave, many parts of the service remain in a very precarious position.

Key headlines from the latest data:

COVID-19 overview

- the number of COVID-19 patients in hospital on 10 February is now 39% lower than the peak reached on 18 January (13,410 fewer patients), but remains 10% higher than the peak of the first wave in April 2020 (1,952 more patients)

- to give a sense of the disruption the NHS has faced, in January there were 101,956 COVID-19 admissions, which is almost a third of the cumulative total since the start of the pandemic.

- vaccination progress continues, with 11.1 million people in England now having received a first dose.

Demand for NHS services

- In January, 11% fewer people attended A&E than in December, with the national lockdown likely to be contributing in a number of ways. A&E admissions also fell in January, but both attendances and admissions remain well above the very low levels observed during the first wave of the pandemic. Those waiting over 12 hours from the decision to admit to admission has increased from 333 in September to 3,809 in January, which is a particular concern regarding overcrowding in emergency departments

- the size of the elective care waiting list increased by 60,621 to 4.52 million in December, and the number of people waiting over 52 weeks has increased even further to 224,205 - a huge rise from the pre-pandemic level of 3,097 in February

- positively, activity levels in cancer services in December remained higher than the same time last year, but the number of diagnostic tests carried out remains well below the pre-pandemic level

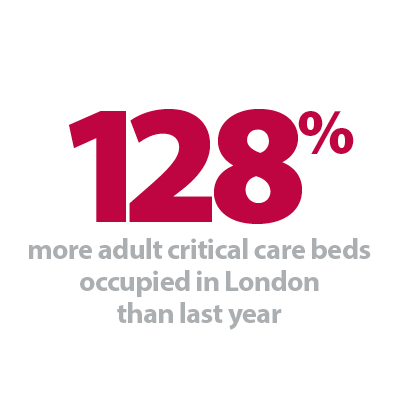

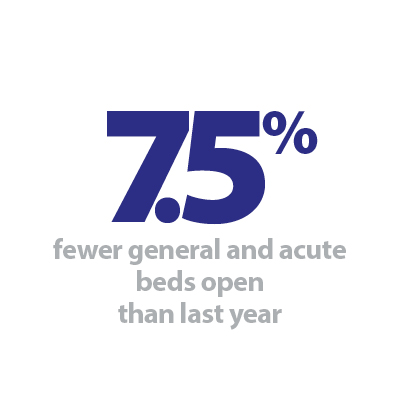

- in the weekly sitreps, the number of critical care beds that are open and occupied have started to fall nationally – but in some local areas these are still rising. Headline occupancy of general and acute beds remains lower than we would normally expect at this time of year, but due to the additional complexities of accommodating large numbers of COVID-19 patients, this will feel far busier

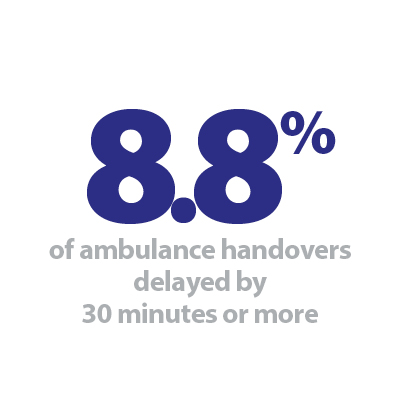

- as the number of COVID-19 patients falls, significant weekly improvements in the proportion of ambulance arrivals that are delayed at the point of handover are being observed. This week, the total number of arrivals remained similar to the previous week, but the proportion delayed by 30 minutes or more fell to 8.8% (from 11.0% last week and a high of 17.2% four weeks ago).

Sickness absence

- January saw very high numbers of NHS staff absent from work. The highest daily figure of the current wave was recorded on 14 January, with 107,882 staff absent from work. 56,175 of these were COVID-19 related (52.1%). By the beginning of February this reduced slightly to 91,652 total absences, of which 41,175 were due to COVID-19.

COVID-19 continues to be the main story of this winter, and even though the number of new cases and the subsequent demand on hospitals are now falling, normal conditions are still a long way off. Trusts have opened a huge number of additional critical care beds to accommodate the sickest patients, and because of the nature of the virus, we will continue to see significant numbers needing this level of care in the coming weeks.

It is encouraging that many of the factors that combine to create regular 'seasonal pressures' have been far less prominent this winter. Length of stay, as well as the prevalence of flu, diarrhoea and norovirus, have all been much lower than previous years. Often, we also see the number of ambulance arrivals and overall bed occupancy ballooning over the second half of the winter period, but these have similarly remained stable in recent weeks. Much of this can be attributed to the different requirements of the COVID-19 response. The reconfiguration of services that has taken place, including the increased infection prevention and control measures, have changed the way care is delivered. It will take time for the critical care pressures to recede and activity levels to be recovered in full across all non-COVID pathways.

The effect on staff is rightly identified as a key priority for health leaders, and the latest sickness absence figures are a bleak reminder of this. For such large numbers to be unable to work at this period of unprecedented pressure underlines both the personal impact the virus is having on those working on the frontline, as well as the ongoing operational challenges trusts face in order to provide care for all who need it.

This week's Winter watch contribution is from Professor Neil Greenberg, a consultant occupational and forensic psychiatrist from King's College London. He highlights the detrimental impact the pandemic has had on healthcare workers’ mental health and wellbeing, and the important steps healthcare leaders will need to take to protect staff in the coming months. Additionally, we have the next edition of our winter podcast series, which features Claire Helm, NHS Providers senior analysis manager, and Julian Russell, NHS Providers senior research analyst, who discuss the trends in the recent data, and what we can expect in the remaining weeks of winter.

Winter Watch: Balancing Acts

In this virtual recording, we have a quick chat with experts from our very own NHS Providers analysis team, Claire Helm NHS Providers senior analysis manager and Julian Russell senior research analyst, about the developments in COVID-19 pressures, the impact of infection prevention measures, and what trusts can expect in the coming months.

Released: 11 February 2021

Recorded: 5 February 2021

How leaders can protect their staff

Neil Greenberg, professor of defence mental health at King's College London considers the way healthcare leaders can support staff during winter and the coronavirus pandemic.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers have been a vital component of the nation’s defence against the virus. Despite a great deal of public gratitude and respect for healthcare workers’ dedication to duty, it is inevitable that exposure to the very pandemic-associated significant stressors, both at work and at home, will leave many staff distressed and an important minority experiencing significant mental health problems.

Many may experience moral injuries, which describes the suffering that occurs when circumstances clash with someone’s moral or ethical code. At the heart of such injuries is often the belief that ‘while I tried my best, it was not good enough’. In the current context, staff under immense pressure may feel that their ability to deliver high quality care has been compromised for a number of reasons – shifting roles, adapting to digital service provision, facilitating patient connections with family and providing increasing emotional care and support for patients who cannot see family.

While our understanding of moral injury is still developing, research from our team at King's College London has identified that many people with moral injuries develop mental illnesses such as depression or post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Healthcare managers will be well aware that protecting staff mental health forms part of their duty of care. However, it is also important that all NHS staff in managerial roles are aware of ‘presenteeism’ which refers to people being at work in body, but not in mind or spirit. Presenteeism is especially problematic in safety critical workplaces, including healthcare, where making poor, slow or incorrect decisions can have disastrous consequences.

So what can be done? It may be useful to think of the answer to this question in two ways. First, what can be done now to limit the psychological damage being done? And, second, how should staff who do unfortunately become unwell be cared for?

It is important to ensure that all staff undertaking arduous or challenging duties, including many healthcare workers and the vital ancillary staff who support them, are properly prepared for their roles. Such preparation is often referred to as 'psychological PPE' and should include frank briefings about the realities of the forthcoming job and making a plan about how to deal with distress prior to being exposed to intense stressors.

The strongest evidence for protecting staff mental health relates to reinforcing social bonds between colleagues and supervisors. Staff should be ‘buddied up’ when going on shift and supervisors should ensure end-of-shift reviews are conducted. It is also vital that all supervisors regularly have ‘psychologically savvy conversations’ with team members. Evidence from high-quality trials shows that training which improves supervisors’ confidence to speak about psychological wellbeing may reduce sickness absence by up to 90%. Such training need not be extensive. A recent pilot of a 60 to 90 minute remotely-delivered training for NHS supervisors led to substantial improvements in their confidence in the use of active listening skills.

There is also good evidence supporting the use of peer support at work. Studies of trauma risk management (TRiM), a peer support package which originated in the military, have found it improves help-seeking and decreases post-trauma sickness absence. There is also emerging evidence showing that reflective practice sessions may help reduce moral injuries and thus protect staff mental health. Such sessions should be leader-led and focus on helping staff develop a meaningful narrative which does not see them blaming themselves or others for perceived failures or poor outcomes.

It is noteworthy that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) specifically warns against the use of psychologically-focused debriefing techniques, which are both unhelpful and may cause harm. This seems to be because intervening with a formal mental health intervention too early risks undermining the normal, and commonly occurring, recovery process. Furthermore, people who are distressed are often in need of time to reflect and discuss with trusted confidants in the short term rather than being provided with interventions that are designed to ‘treat’ people who are formally unwell. Much more beneficial is ensuring that staff’s basic needs are met: reasonable shift patterns, rest areas, and suitable safety equipment are all protective of mental health.

Managers should also ensure that up-to-date and accurate information on local and national supportive services are well advertised. However, many staff who develop mental health difficulties fail to seek help. Unfortunately, organisational mental health screening programmes have not been shown to be effective. That is to say they fail to reliably pick up people in need of treatment and mistakenly label some as requiring formal care when this is not actually needed. But help-seeking can be encouraged by supervisors fostering a supportive workplace environment in which seeking help, when needed, becomes the norm. Where professional care is needed, it should be available rapidly to facilitate a return to work and loss of self-esteem, relationships and careers.

An effective staff mental health plan not only fulfils an organisation’s duty of care, it is morally right, protects staff morale and reputation and improves care delivery.

Further support:

- Our NHS People

- Point of Care Schwartz rounds

- Health Education England training on Freedom to Speak Up

- National Guardian’s Freedom to Speak Up in Healthcare training

NHS still under severe strain despite fall in COVID-19 admissions

Responding to the latest monthly combined performance data, and winter reporting data from NHS England and NHS Improvement, the chief executive of NHS Providers, Chris Hopson said:

"The NHS continues to be under enormous pressure, with over 100,000 people admitted into hospitals with COVID-19 in January. Critical care facilities, in particular, are under severe strain. Separate data shows that while we are now coming down from the peak of this wave, hospitals are still treating 10% more COVID-19 patients than the peak of the first wave in April 2020.

"Monthly statistics released today show that A&E attendances fell in January, but the number of people waiting over 12 hours to be admitted has reached over 3,800.

"Despite COVID-19 pressures, the NHS still managed to diagnose and care for cancer patients throughout December, with activity levels higher than the same time last year. The number of people who saw a consultant following an urgent GP referral reached over 200,000 and more than 25,000 people started cancer treatment, both back to pre-pandemic levels.

"NHS staff are working tirelessly to carry out as many operations as possible in the current circumstances. However, the number of people waiting longer than 52 weeks has now reached over 224,000 and the total waiting list stands at 4.52 million. The government, national bodies and the public will need to be realistic about the time it will take to tackle this backlog, recognising the impact these strained pressures have placed on an already overstretched workforce.

"More positively, other parts of the system are starting to benefit from the reduction in COVID-19 admissions. It was particularly encouraging to see the marked reduction in handover delays for patients being transferred from ambulances to hospital, to the lowest level this winter or last. Reducing handover delays means that ambulances can quickly answer new calls, and get back to the community to care for people more rapidly.

"The figures paint a picture of the NHS trying to carry out as much non-COVID care as possible in a really difficult context. While there are positive signs, thanks to the hard work of NHS staff across all sectors – acute, ambulance, community and mental health – we are not yet out of the woods. Adhering to the lockdown measures continues to be the key to reducing COVID-19 pressures across the NHS and it’s vital that people continue to comply with restrictions."