The 2021 SR funding injection followed years of prolonged underinvestment in estates and facilities across the NHS, and the capital maintenance backlog remains a major concern for trusts. While the SR uplift was welcome, the concern remains that national capital expenditure limits do not fully reflect the NHS’ investment needs. Indeed, as The King’s Fund notes, “the full ambitions of the NHS capital regime will not be achieved – even if improvements to capital allocations are implemented – if the overall amount of NHS capital investment is insufficient”.

As we cover in this section, the level of the maintenance backlog and the extent of dilapidated infrastructure ultimately reduces the ability of trusts to transform their estate and make vital productivity improvements.

Investment in estate renewal and scale of maintenance backlog

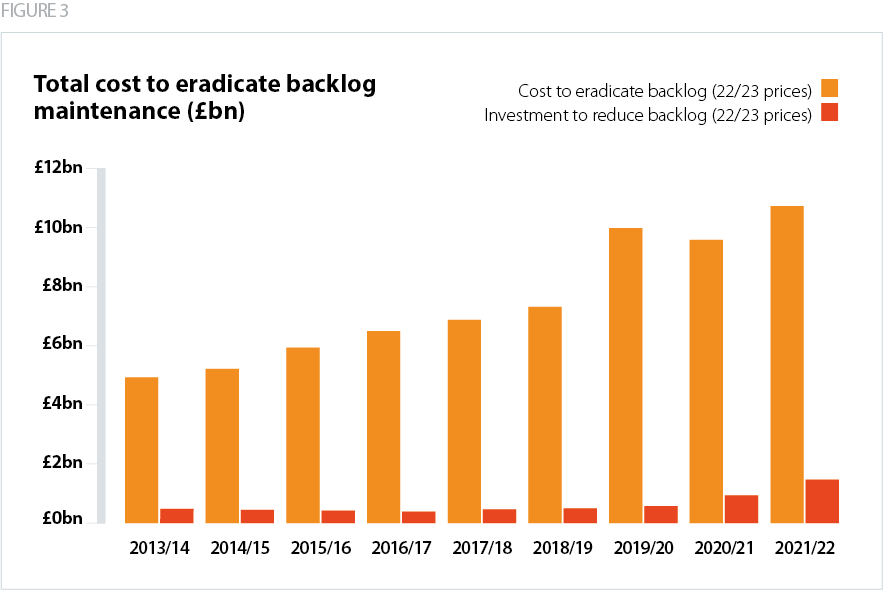

The latest estates return information collection (ERIC) data for 2021/22 shows a major deterioration of the ‘backlog maintenance’ across the NHS estate. This is a measure of how much needs to be invested to restore assets to suitable working condition (based on a set of assessed risk criteria). The backlog refers to work that should already have taken place.

Source: NHS Providers analysis of 2021/22 estates returns information collection (calculated using December 2022 GDP deflators).

Since 2010/11, the total backlog has more than doubled which highlights the sustained underinvestment in the NHS estate. Despite a major increase in capital investment in 2021/22 totalling £1.47bn (in 2022/23 prices) to reduce the maintenance backlog, the latest data shows that the backlog increased to £10.75bn.

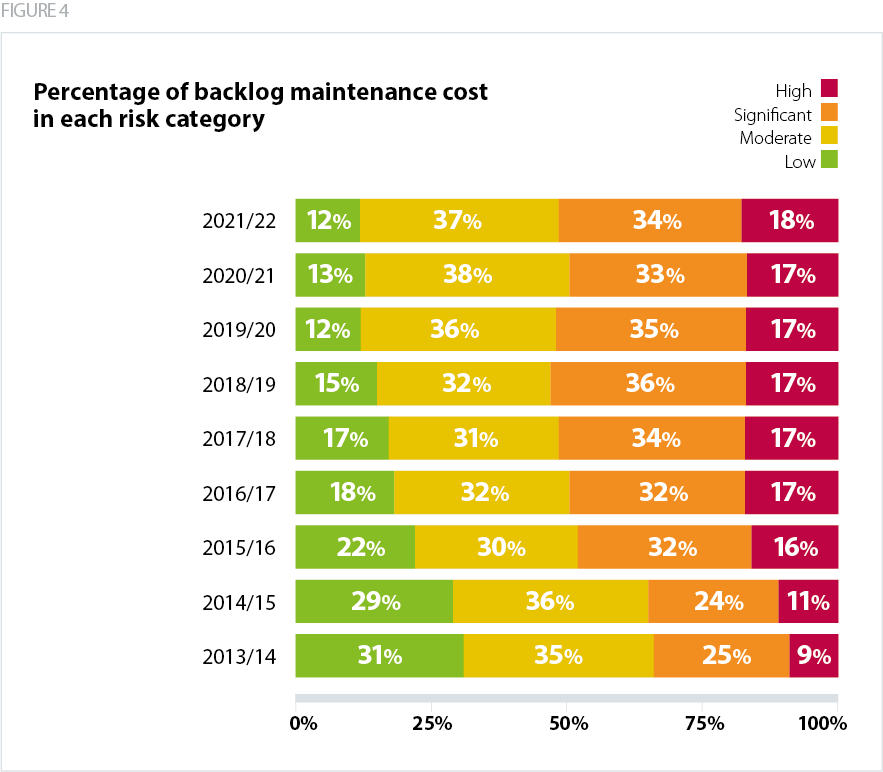

The need to prioritise critical infrastructure risk

In 2021/22 the total cost to eradicate the highest maintenance risk was £1.89bn in 2022/23 terms – four times the 2013/14 level. The proportion of the backlog which presents a high or significant risk has increased to 52% – £768m more in 2022/23 prices. 'High risk' refers to repairs which must be urgently addressed to prevent catastrophic failure or major disruption to clinical services, and significant risk is where repairs demand priority management and short term spending. Positively, the number of estates and facilities related safety incidents fell by over 40% when compared to 2020/21 figures.

There is a recognition across government and by trusts of the need to provide more granular levels of data on the scale of infrastructure risk across the estate. The Public Accounts Committee has recommended that DHSC and NHSE should provide an annual progress update about how ICSs are managing to address the maintenance backlog.

Reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) planks

There is also a significant estates risk presented by reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) planks used in construction between the 1960s and 1980s. These were used for flat roof construction and span between steel beams or on masonry walls. This type of precast concrete was expected to have a lifespan of around 30 years, but some trusts have used these materials for over 50 years. To mitigate the risk of sudden collapse, organisations may replace the planks with alternative structural roofs or introduce secondary supports such as scaffolding.

There are currently 14 hospitals with RAAC planks which will require extensive building work to prevent their closure. Of the 14 hospitals, seven are at a critical level of risk and only two of these are currently included in the government‘s New Hospital Programme. The government has committed to remove RAAC from the NHS estate by 2035 and has allocated £685m mitigate the risks. However, it is currently unclear how much additional capital will be made available for trusts impacted by RAAC planks, whether the government will implement a separate funding stream to deal with the issue, and if the remaining places on the NHP will be taken by RAAC-affected trusts.