Summary

The NHS is in a relatively privileged position compared to other public services in having a five-year revenue settlement confirmed with an extra £20.5bn real terms funding increase in annual funding by the end of the five year period to support the delivery of the long term plan. However, trusts and the wider health and care system are still operating under severe financial constraints. The additional funding provided with the plan equates to a real-terms increase of on average 3.4% per year for five years. However, this is lower than the average increase of 4% across the period between the establishment of the NHS in 1948 and 2010 when the period of 'austerity' began and comes at the end of a prolonged period of efficiency savings. While the 3.4% average increase will allow the NHS to keep up with the growth in demand at existing levels, it will not be enough to recover performance and finances, and cover the additional costs of transforming services to deliver integrated, personalised care for the public.

The provider sector is also still in need of an appropriate multi-year settlement for capital investment. The additional injections of capital announced in August 2019 alongside 20 'hospital upgrades' and the subsequent government commitment in late September 2019 of £3bn to be spent between 2020 and 2025, to rebuild six hospitals, invest in new diagnostic equipment such as CT scanners and provide seed funding for a further 21 hospital schemes, are of course extremely welcome. However, the 10% uplift on the NHS capital this provides still falls short of what is required to clear the maintenance backlog and invest for the future. We are yet to understand the allocations annually up to 2025, and the spread of the schemes to be allocated seed funding, across acute, mental health, community and ambulance providers.

In addition, severe funding constraints and uncertainty for key services outside of the core NHS budget such as social care and public health, risk exacerbating the pressures on the NHS by driving further increases in demand for secondary care which could be better met through appropriate investment in a preventative approach, in primary care, social care and in additional capacity within the community.

The provider challenge

Reducing the provider deficit and improving the financial framework

The financial position of the provider sector has deteriorated considerably in recent years as demand for services has risen. The funding mechanisms for services such as A&E have been a core driver of acute trust deficits. There is also clear evidence of under investment over a period of years in services such as community services for adults and children, gender identity services and crisis home treatment teams. Fundamental community services like health visiting and sexual health services have come under pressure from local authority cuts.

While all providers face financial pressures, trust deficits are largely concentrated in the acute sector. Nearly half of trusts (107) were in deficit at the end of the 2018/19, a small minority of which had small, structural deficits. The provider sector's outturn position for 2018/19 was a £571m deficit, increasing to £827m when technical adjustments are taken into account. In fact, the "underlying" deficit for the provider sector is estimated at £5bn taking into account one off payments, loans and technical measures.

The long term plan describes a recovery trajectory requiring the number of trusts in deficit to be reduced by half in 2019/20, the provider sector as a whole to be in balance by 2020/21, and no providers in the red by 2023/24. We are currently working closely with NHS England and NHS Improvement as they develop their proposals to amend the financial policy framework to better support trusts to recover and maintain financial balance. This year's planning guidance begins to set out an approach towards using the new money to deliver financial recovery: increasing funding for accident and emergency services, which are driving most deficits, strengthening the mental health investment standard to come good on the government’s commitments to parity of esteem, establishing a new financial recovery fund (FRF) to help challenged providers stabilise their finances, and removing central risk reserves to increase core funding.

However, resolving trust deficits will take time. It will require the provider sector to make savings and efficiencies at roughly the same rate as during the lean years at over £3bn a year in addition to receiving additional funding from the £20.5bn, which will be routed through payment mechanisms. NHS Providers has said many times that this rate of cost reduction is simply unsustainable, not least because the efficiency improvements capable of generating the largest impacts with lowest impact on service delivery will already have been made, early in trusts' efficiency programmes. The need to contain costs may force trusts to make non-recurrent savings (which are increasing as a proportion of the total provider sector cost improvement programme as providers exhaust the most easily achievable recurrent savings). This could take the form of delayed maintenance work, staff vacancy freezes, or delayed investment in service transformation.

Finding cost improvements at the same time as transforming care to deliver the aspirations of the plan will be a considerable ask of any trust board.

I am concerned about the scale of the transformation that is required, the nature of the shift in mindset that is needed at all levels within the NHS when we will be held to "old world" performance measures, all at a time when the system is under immense and unsustainable pressure.

Acute Trust

Our capital programme is very limited and significant transformation and improvements in efficiency require a reasonable capital investment.

Acute Trust

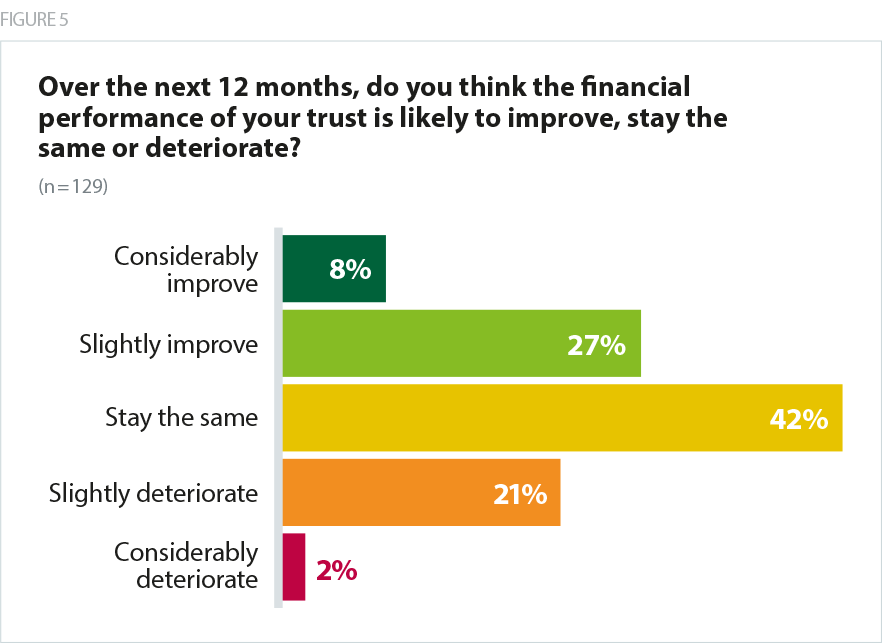

Only 35% of respondents to our survey thought their trust’s financial performance would improve over the next 12 months, with 23% predicting financial performance would deteriorate.

Respondents from acute trusts were more likely to predict that their finances would improve (51%) than all other types of provider, possibly because of changes in payment mechanisms and financial flows within the system.

Capital investment in the NHS

The cumulative impact of years of under investment

The NHS requires significant capital investment to maintain buildings, modernise facilities, and invest in new treatments and IT, but capital spending by trusts has been severely constrained since 2010. Capital has not been given the same protection as day-to-day spending, in fact the NHS has suffered in recent years from repeated capital to revenue transfers to support day to day running costs for providers. According to The Health Foundation, the Department of Health and Social Care's (DHSC) capital budget fell by 7% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2017/18 (The Health Foundation, 2019). Meanwhile, the share of the department’s capital budget available to NHS providers fell even more sharply, by 21% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2017/18. The decade-long squeeze on revenue funding also added to the pressures, as trusts have been unable to generate surpluses which could have been used to make capital investments.

Successive years of inadequate capital funding have created a severe backlog and providers now need to make a wide range of safety-critical investments that they can no longer delay. At the same time, partly due to national allocation mechanisms, there is a danger of a mismatch between where funding available sits at individual provider level, and the places most in need of capital investment. In addition, it is now harder than ever for trusts to access private capital as the government has declared the private finance initiative (PFI) no longer an option, without setting out alternative arrangements beyond additional injections of government funding.

Furthermore, the NHS capital regime – that is, the capital bidding, prioritisation, allocation and approvals process – is in need of rapid reform. The Treasury asked DHSC to conduct a review of the regime in January 2018 which has yet to be published. All capital spending, irrespective of whether it is funded by DHSC or a trust’s own funds, counts against the department’s capital departmental expenditure limit (CDEL). There is, therefore, a risk that foundation trusts could collectively overspend the DHSC’s capital budget, raising pressure on NHS England and NHS Improvement to control spending. Furthermore, trusts in long-term deficit have already used up their cash reserves and would require several years in surplus before their balance sheets are in a sufficiently healthy state that money could once again be invested in estates and facilities.

As a consequence, the provider sector has struggled to make the necessary investments in new buildings, equipment, IT and digital technology, and many providers have been unable to invest in ways that will enable them to become more efficient, deliver transformational changes, and match physical capacity to increasing demand. The most recent figures available show that in 2017/18, there was a £6bn capital maintenance backlog, of which £3bn relates to high – or significant – risk maintenance.

The trust has two significant capital developments that will enable it to secure services and meet demand in the next three to five years. It’s incredibly difficult to progress these in the current climate and with STP service reviews taking place. I'm worried that these are not going to deliver significant change and that estates transformation will only be delayed while this becomes obvious, leading to significant capacity problems.

Acute Trust

Feedback from trusts demonstrates the very direct and significant impact this has on patient care:

Anti-ligature works delayed. Impact on service delivery, impact on staff, additional revenue costs.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust

Delays to implementation of reconfiguration of high risk general surgery and major trauma pathways.

Combined Acute and Community Trust

NHS Providers survey of trust finance directors, July 2019: responses to the question "If your actual capital spend was less than plan, what was the impact?"

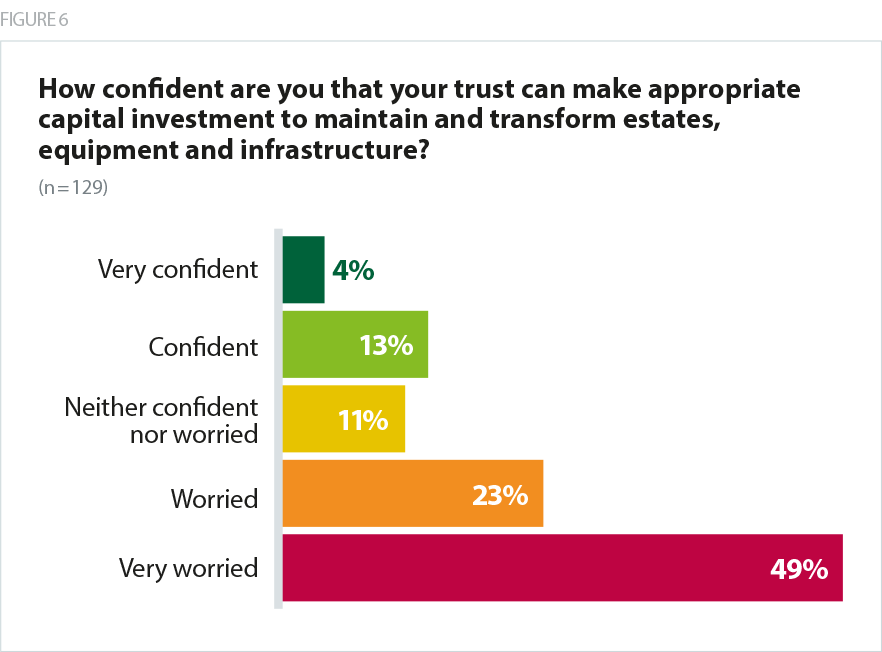

When asked how confident they were that their trust could make appropriate capital investment to transform estates, equipment and infrastructure, more than seven in 10 respondents to our survey (72%) said they were worried, with only 17% indicating that they were confident they would be able to do this. A greater proportion of respondents from acute trusts (82%) and combined acute and community trusts (85%) were worried than the other types of trusts, possibly because of the greater requirement for expensive specialist equipment at these providers.

The impact of recent announcements on increasing capital funding

Prime minister Boris Johnson recently announced £1bn additional spending power for the NHS to spend on vital improvements to facilities in 2019/20, plus an additional £850 to cover 'upgrades for 20 hospitals'. In September 2019, this was supplemented by a welcome commitment from government to rebuild six acute hospitals, invest £200m in new diagnostic equipment and provide seed funding for a further 21 hospital schemes between 2021 and 2025. However it was deeply disappointing that no mental health, ambulance or community investment was.

We are extremely pleased to see the priority the government is now placing on NHS capital investment. However, welcome as this is, the estimated 10% uplift on the NHS capital (our estimate based on government’s announcement of new £3bn for capital over 5 years), these announcements still fall short of what is required to clear the maintenance backlog and invest in modern, innovative care for patients for the future. We calculate that the current NHS capital budget of circa £6bn a year needs to double over the next five to 10 years to address the maintenance backlog and meet patient need. This would match current capital spend in comparable countries, ensure safe care and help create the right environment for staff (OECD, 2017).

We are also keen to understand the annual allocations of the additional £3bn investment, in the period 2021 to 2025. As the NHS does not have a capital budget set beyond 2020/21, it will be important to ensure that the extra funding for 2020-25 does translate into a £3bn increase to the current CDEL baseline over that time. While investment in acute estate is very welcome, mental health, community and ambulance providers have equal needs for capital funding. We are therefore keen to understand the spread of the schemes to be allocated seed funding.

Finally, there remains a need for reform to the process by which all trusts access capital investment. Welcome as recent announcements have been, the NHS needs a long term, sustainable approach to capital allocation and prioritisation.

As we have set out in our Rebuild our NHS (NHS Providers, 2019f) campaign, despite these announcements, which mark a real step forwards, the NHS still needs:

- a multi-year NHS capital funding settlement

- a commitment from government to bring the NHS' capital budget into line with comparable economies

- an efficient and effective mechanism for prioritising, accessing and spending NHS capital based on need.

Residual gaps in funding

The NHS will not be on a sustainable footing until there are also long-term settlements for social care, public health, and education and training. Underfunding these areas has the potential to increase demand for NHS services:

- Social care – funding for social care has been reduced over the past decade in the face of an ageing population and increasing numbers of adults with more severe needs. The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services' (ADASS) most recent budget survey describes a £7bn cut in social care funding since 2010. Lack of capacity within the social care sector places additional strain on all health services, including primary care.

- Public health - funding for public health has been cut by 10% since 2015/16. As our The state of the NHS provider sector report on community services sets out, local authority budget cuts have had a direct impact on the commissioning of community and mental health services. This has meant reductions in some areas in services such as school nursing, drug and alcohol services and health visiting for example, all of which play a key role in prevention as well as treatment.

- Education and training – since these budgets have been defined as being outside the NHS ring-fence, there have been cuts to spending on staff development over the past five to 10 years. With around 100,000 vacancies in the service with particular recruitment pressures on nursing and services including learning disability. Major shifts in the model of care planned such as non-consultant led outpatient services, more specialist clinicians working in primary care settings, more imaginative use of the allied health professions and more community care, DHSC will need sufficient resource to fund an adequate and reshaped workforce to deliver the plan. The interim people plan represents a positive step forward in this regard but we are still awaiting a multi year settlement for education and training.

More broadly, our recent report on mental health services, Addressing the care deficit showed clearly the impact of a lack of investment in wider public services during the years of austerity. For example, 92% of trusts told us that changes to universal credit and benefits are increasing demand for services, as are loneliness, homelessness and wider deprivation (NHS Providers, 2019a).

Main impact is from high and increasing levels of deprivation in this post-industrial area - so the main determinant is economic. Locally, substance misuse is rising rapidly and funding of provision for care and treatment via local authorities has more than halved - the consequences were and are self-evident. Also provision is a lottery with, for example, one CCG funding adult eating disorder care and the adjacent one not.

Mental health / learning disability trust

Cuts to local authority and voluntary sector budgets have dramatically reduced the availability of services - The NHS is the only one still "open"!

Mental Health / Learning Disability Trust

NHS Providers Survey on mental health

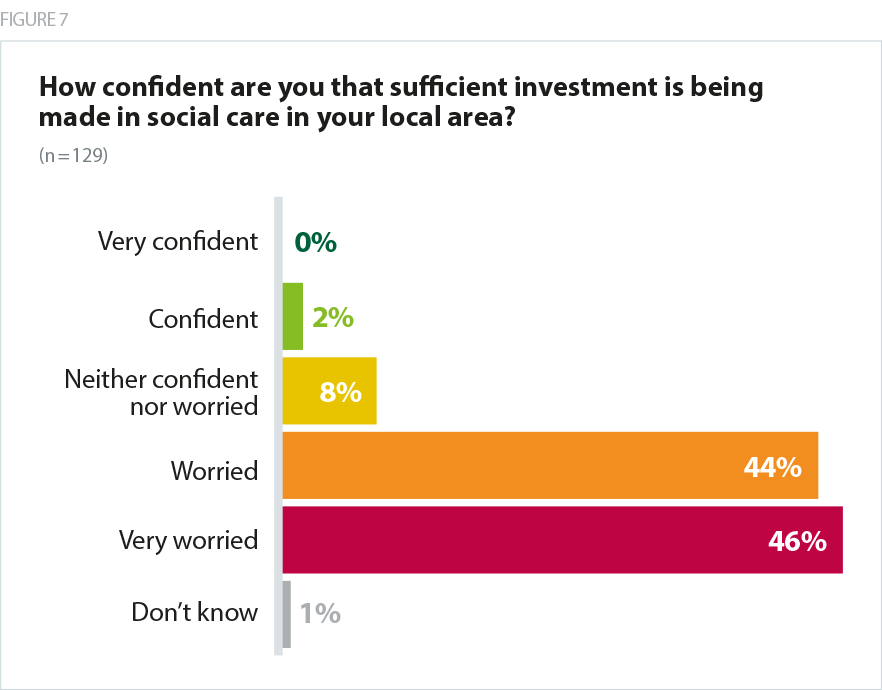

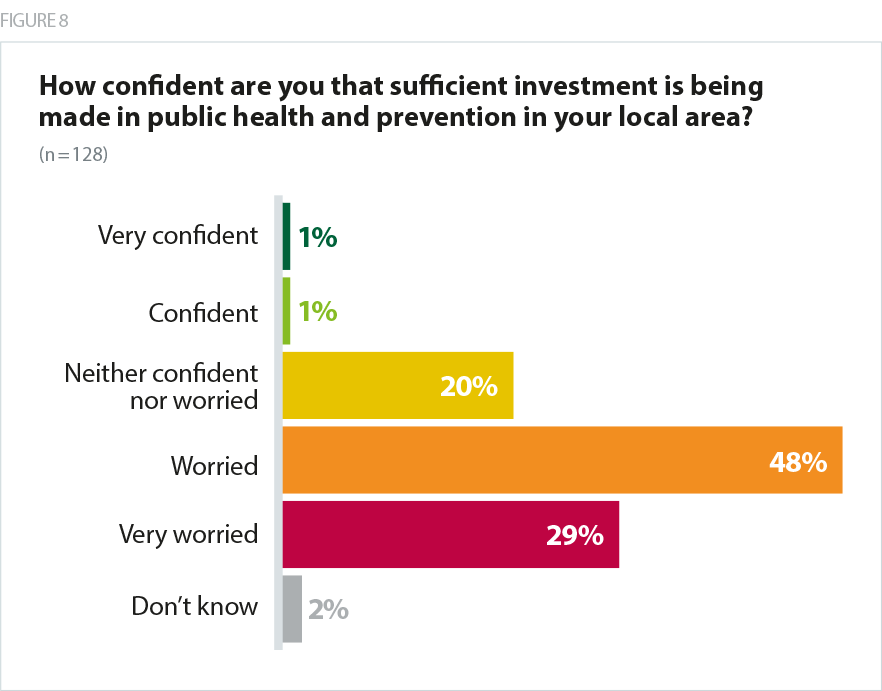

Trust leaders had significant concerns about public health and social care services – 90% of survey respondents were worried that sufficient investment was not being made in social care in their area, with only 2% being confident that sufficient investment was in place. 77% were worried about public health funding (again only 2% were confident).

The widespread erosion of social care and community infrastructure is having a huge impact on NHS services. We need to look at different models of collaboration that allow NHS providers to inject capital and other forms of investment into non-NHS care.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust)

Public health budgets are continually being cut and not enough is being spent on prevention. Our health visiting service and school nursing service were recently tendered and we had to deliver significant cuts to services to win the contract.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust

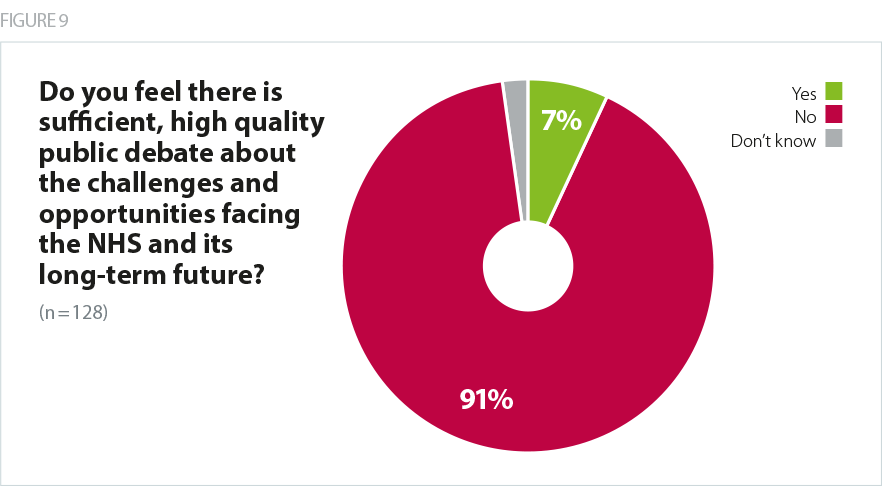

Most telling, given the scale of challenge, and opportunity, facing the NHS, more than nine in 10 respondents (91%) did not feel there was sufficient high quality public debate about the challenges and opportunities facing the NHS and its long term future.

Public debate at the moment is as awful as I can remember it being in my life. There is some good quality discussion within the service, but politically the quality of discussion about the service and about social care is an embarrassment.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust

There is debate but given the focus on Brexit I don't think we are anywhere near having the sort of conversation we need with the communities we serve about the choices and challenges ahead.

Community Trust

How providers are responding

NHS Providers is actively engaged with NHS England and NHS Improvement in helping to reshape the national financial policy framework in support of a sustainable trust sector. This involves a range of detailed engagement on payment mechanisms, financial incentives within the system, the operation of the FRF and the process by which trusts access capital investment.

While revising the financial architecture to ensure more funding flows directly to trusts will be key in returning the provider sector to financial balance, trusts have historically delivered significant efficiency savings, and continue to find savings wherever possible without damaging patient care. Examples include East Midlands Ambulance Service adopting a more efficient approach to refuelling ambulances, the growth of collaborative working to deliver back office services such as a collective of acute trusts in west Yorkshire under the West Yorkshire Association of Acute Trusts partnership and the use of telemedicine in the Morecambe Bay area involving 11 partner organisations including University Hospital Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust who explored how to reduce unnecessary patient and ambulance journeys.

Trusts are also making the most of innovative and collaborative partnerships in local systems to ensure they make the most of the collective pound in any given local area. This may include making the most of the available estate to deliver integrated services with partners such as primary care and working closely with local authorities which have more flexible access to funding.

Trusts also continue to generate non-NHS income where appropriate to reinvest in NHS care. This may stem from a private patient ward within an NHS building, growth of the charitable arm of their business or commercial partnerships. We know that financial pressure is one driver of the development of new business models including subsidiaries and wholly owned subsidiaries.

What does this mean for patients and service users?

The additional £20.5bn funding provided alongside the long term plan clearly supports the NHS to maintain good quality care for patients in the medium term. However, the scale of the deficit reduction task facing providers, the gaps in funding for services outside of the core NHS budget, and capital constraints will equally have clear consequences for the nature of the services available to patients and the public, and the staff who work within the NHS.

We expect demand to continue increasing faster than the NHS’ capacity to respond across the acute, specialist, community and mental health sectors. This risks an overstretched NHS workforce seeking to support high bed occupancy rates, with longer waiting lists for care and longer ambulance response times, all of which can carry associated safety risks. With increasing pressure on our A&E departments and inpatient beds, trusts will struggle to balance their commitments to urgent and emergency care, and elective care. Our recent reports into the state of care within mental health and community services revealed concern around adequate investment in community services for adults and children such as gender identity services and crisis home treatment teams (NHS Providers, 2019a). Fundamental community services like health visiting and sexual health services are also under pressure from local authority cuts.

Without a multi-year settlement for capital funding which sees a doubling of the funding available, providers will struggle to maintain estates and equipment, and be unable to invest in innovative and specialist technology. This has a direct impact on the experience of patients, service users and staff and can impact on patient safety as providers become unable to meet fire safety requirements or to respond to issues raised in CQC inspection. It can mean use of outdated CT scanners, lack of the latest equipment available for paramedics and community services, over crowding in A&E departments simply not designed for the volume of patients trusts see today, or lack of investment to tackle ligature points within a mental health setting.

Without sufficient investment in public health and a shift to a more preventative model of care, the health and care sector will remain trapped in current models of delivery. Additional funding for public health could radically transform how we address the impact of the wider determinants of health in England such as housing, education and transport, support individuals to make healthier choices, and increase the success of health focused, preventative campaigns, be that to increase screening for particular conditions or to raise awareness of health risks.

Without sufficient investment in social care to stabilise the system, users of social care services and their relatives will continue to find the capacity of those services to respond in a timely way, the level of personalisation, and the care packages available limited until a more sustainable approach to the funding and provision of social care can be achieved by government through a cross party endeavour.

Within this context we must be realistic about how far the NHS can meet rising demand within existing models, and seek to transform and develop more integrated models of care which could improve patient experience and outcomes.