Summary

The long term plan places system working and population health at the heart of work to improve care quality and ensure services remain sustainable. The plan gives ICSs, whose membership comprises local NHS organisations and local government, a central role in leading this system working. There is a target for the whole of England to be served by an ICS by April 2021, and at the local ‘place’ level, primary care networks are being set up across the country to drive integrated working.

However, the measures set out in the long term plan to embed system working are ambitious, and rest on the ability of local partners to forge new relationships and to embed new ways of working within an existing legislative framework based on institutions not local systems. Success also depends on the national bodies’ ability to ensure that national policy and regulatory frameworks consistently support system working rather than the established, organisational focus.

The Provider Challenge

Risks and opportunities presented by system working

The development of system working is the core driver of change within the long term plan and presents an exciting opportunity for trusts and their partners to work together to adopt a population health based approach, better integrate services and ensure more sustainable care which makes the most of the collective pound in a locality. However, the scale of the change, and the support required, for trusts and their partners to move towards a new ‘operating model’ framed around system working must not be underestimated.

There is much more to do to ensure that policy and regulatory frameworks appropriately and coherently support system working and to embed the development of new regional NHS England and NHS Improvement structures. This will be a complex endeavour given that statutory responsibilities rest in the component organisations within an STP and ICS – and given that the STP and ICS footprint will not always be the logical footprint for service delivery. In addition, patient flows often cross system boundaries, including for key services such as cancer networks, and the footprints for specialised services and ambulance services cover a much wider geography.

The shift to system working involves a radical transformation of the commissioning landscape to accommodate fewer, more strategically focussed CCGs. It also creates a backdrop for different forms of provider collaboration, and new integrated partnerships and alliances, which cross traditional organisational boundaries to form.

NHS Providers has been pleased to support emerging thinking around the development of a new operating model for the NHS which reflects agreed values and behaviours between national, regional and local leaders,and reflective of this fundamental shift away from competition and towards a more collaborative way of working. However, it is hard to overstate the scale of the transformational challenge ahead for the health and care sector as a whole, as well as for providers specifically.

Trusts and their partners must therefore find the leadership capacity to invest in new relationships and a transformative agenda for patient care, at the same time as tackling financial constraints, rising demand and workforce vacancies. Trusts also face sustained pressure from the regulators to focus on improving their own performance against organisationally framed measures (including the NHS constitutional standards). This means that trust boards and their staff are stretched thinly across multiple priorities.

Providers' views of system working as a driver of change

Although there is widespread support across the sector for greater collaboration within local systems (rather than the competitive approach initiated by the 2012 reforms), there are mixed views, and a mixed evidence base, as to how far integration in local systems will prove to be the solution to all of these issues. Our survey results show clearly that trust leaders lack confidence in how far system working alone can address some of the fundamental issues facing the NHS, particularly the need to address workforce shortages and to place the system on a financially sustainable footing.

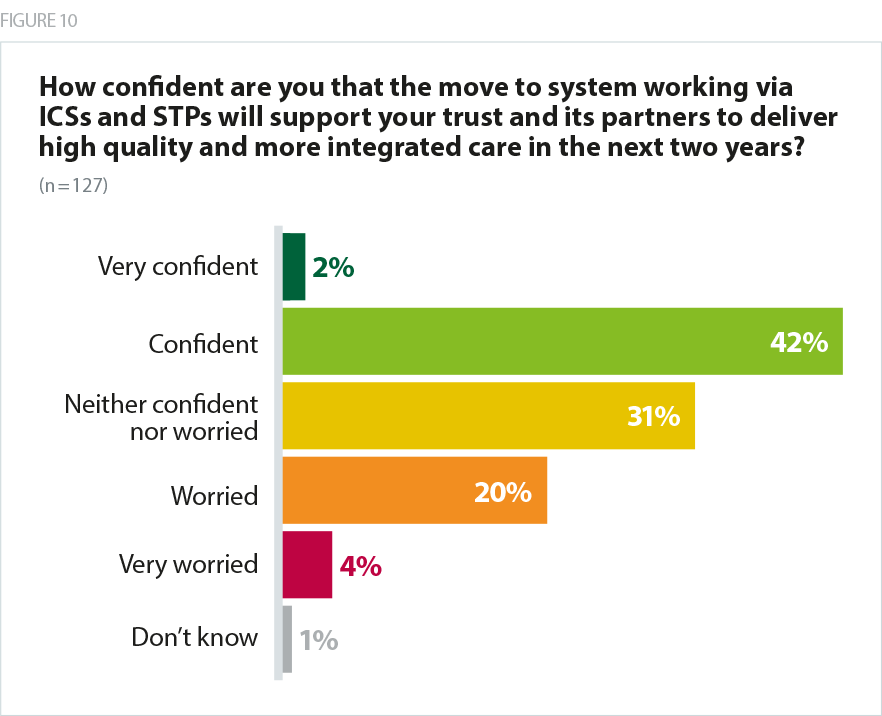

On a more positive note, nearly half of respondents (44%) were confident that the shift to system working via STPs and ICSs would support them and their partners to deliver high quality, more integrated care in the next two years.

The STP is a good vehicle for us as a specialist trust to ensure best pathways of care across primary and secondary care ensuring equity and good quality services across the region. There has been some good work on organisations working together for improved patient pathways in a number of conditions in several speciality areas and priority areas of work.

Acute Specialist Trust

If we allow place models with lead providers to develop then we have a chance of progressing integration more rapidly without the negative impacts of CCG procurement.

Combined Acute and Community Trust

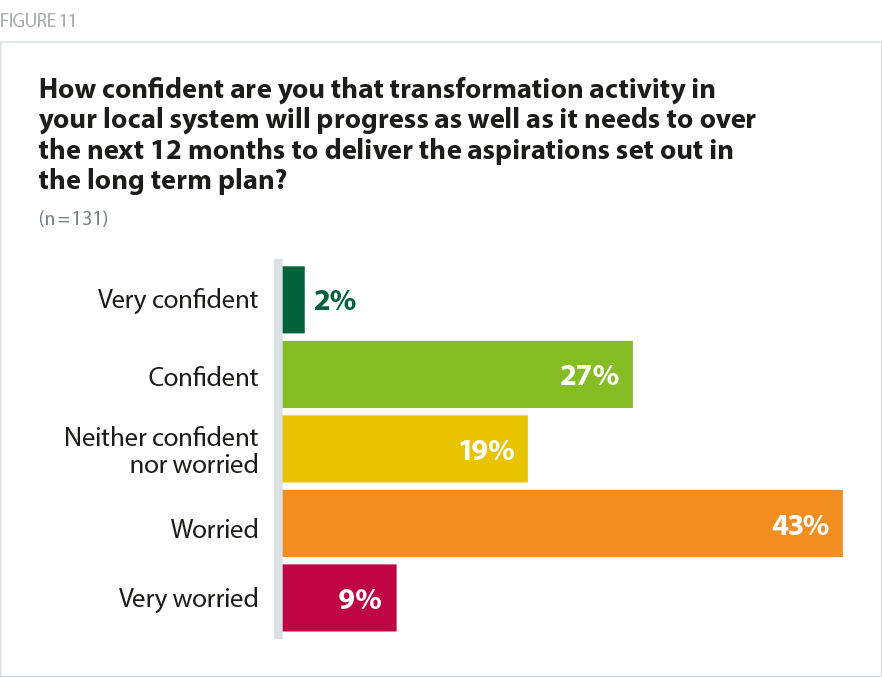

However, only 29% of respondents were confident that transformation activity in their local system would progress as well as it needed to over the next 12 months in order to deliver the long term plan’s aspirations.

Very recent relationship building and some new players have, at long last, created a basis for new confidence. However, underlying deficits are deep and intractable and the absence of any level of certainty about workforce and capital availability cast significant doubt.

Mental Health / Learning Disability Trust

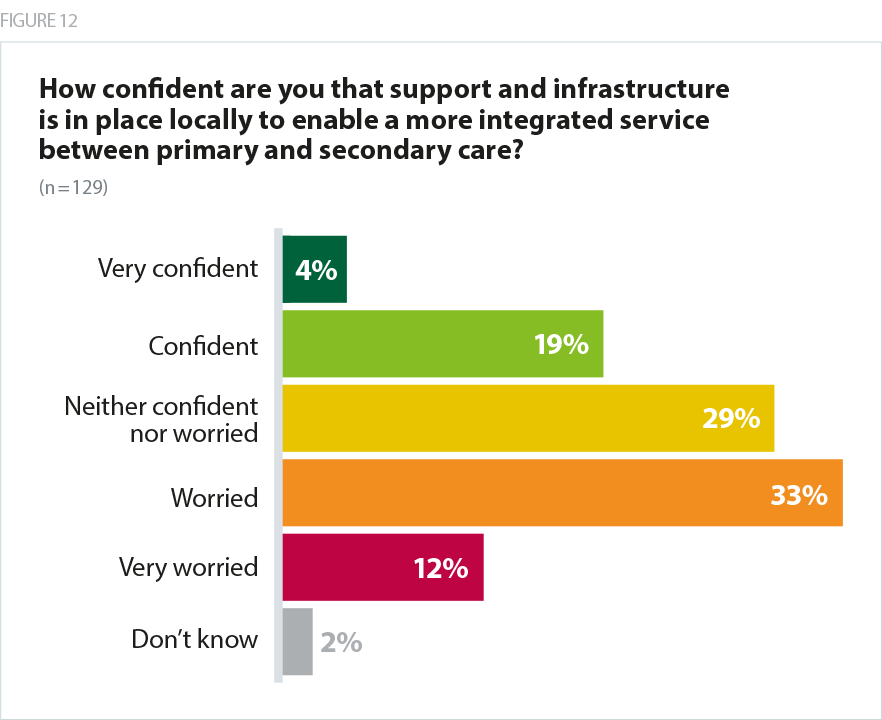

Only 23% of respondents overall were confident that the support and infrastructure was in place locally to enable more integration between primary and secondary care.

I think the creation of PCNs is a double edged sword and potentially a missed opportunity. It would be very frustrating if in the move towards greater integration and a rationalisation of CCGs we end up with a more fragmented system if the PCNs are not aligned with the transformation required.

Acute Trust

Only 17% of respondents were confident system working would support their health economy to become more financially sustainable over the same period. Only 13% of respondents were confident that system working would support the ability of their trust and its partners to recruit and retain an appropriate workforce over two years.

I can't see yet that the STP has any control over finances. That stays with the CCG(s) and their commitment to 'system' remains uncertain.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust

I don’t think that an ICS will help in any way. Conversely, it feels like a strategy to push more of the problems down to local leaders. As a strong foundation trust, I also worry that this is simply a strategy to seek to use efficient organisations to bale out those less so. While this may be necessary, we need to have a strategy to improve the weaker organisations not just simply dilute them.

Combined Acute and Community Trust

The role of the trust unitary board in system working

ICSs and STPs currently have no statutory basis and their success rests on the ability of their component organisations – trusts, CCGs, local authorities, primary care and the community and voluntary sector – to work together to plan how to improve health and care. Crucially, accountabilities within the system therefore continue to rest with the component statutory organisations within an ICS or STP, primarily the NHS trust or foundation trust, CCG and local authority.

This creates new opportunities and new risks for trust boards as system working relies on the development of robust, local relationships, which will take time to develop in those areas where close partnership working is new. It also means that trust boards must work with their partners to develop governance mechanisms which allow for collaboration and collective responsibility without blurring a line of clear accountability to the public, to parliament (for foundation trusts) and to other bodies for board level decisions.

However, providers have a strong history of collaboration and innovation with different partners and there is nothing within the current legislative framework which prevents collaboration. Indeed, taking a broad view of a foundation trust's duties to "maximise the benefits" of the NHS to the public as a whole – not just those who come through their doors – means providers arguably have a duty to ensure the good of all NHS services, not just those that run themselves.

There are questions yet to be answered about how best to ensure non-executive oversight and challenge of system level decisions. Trusts and their partners will welcome new forms of support as boards scrutinise and contribute to their organisation's contribution to wider system plans. However, on balance, bringing together different parts of the NHS should present the opportunity to build on what is best about corporate governance in the NHS. Within that the retention of the unitary trust board is essential to achieve best practice in corporate governance.

A population health-based approach

The stated aim of the long term plan was to transform how care is delivered and to move towards a more preventative approach to healthcare. If we are to do this, government will need to invest appropriately in public health, and give equal attention to those services which address the wider determinants of health. Trusts are embracing the prospect of moving to population health based approaches, but will require time and support to embed and make use of the data and analytics which underpin this.

New neighbourhood level partnerships including primary care

Community service providers play a key role in the development of integrated local systems. Users of community services often have multiple conditions and frequently receive social care support. Therefore, due to the nature of these services, the community workforce tends to be highly aware of the role of other providers in caring for patients and service users. Some of the changes set out in the long term plan have the potential to further deepen the community sector’s links with other parts of the health and care system.

One such area of opportunity is the development of PCNs. For historic and contracting reasons, primary care has tended to operate relatively independently from other parts of the NHS. PCNs aim to bridge this long-established divide between primary and community care by building out from a core of primary care provision to a network that involves working with community services, social care, the voluntary sector, mental health, pharmacy and acute hospitals.

However, there are challenges inherent in creating these new neighbourhood level systems. Notably, community providers in many areas have been working with colleagues in acute and mental health trusts for some time to provide integrated services at locality level. Some community providers have already reported difficulties in working out how to align existing multi-disciplinary team structures and workforce arrangements within new PCN boundaries.

Second, some of the staffing requirements that have been placed on PCNs, in particular to have specific roles such as paramedics, pharmacists and social prescribers, could place local labour markets under pressure if trusts and their partners within PCNs do not work closely together. As PCNs are not bound by Agenda for Change remuneration requirements, they are potentially able to pay staff higher wages, which could disadvantage existing community providers.

Forging strong local relationships will be critical to the success of this new way of coordinating care. The tight timescale for getting PCNs up and running will make establishing these relationships early even more critical.

Integration with social care

The NHS relies on a healthy social care sector to operate efficiently and vice versa. Cutting social care places has increased pressure on NHS services, and can result in delays for patients who are ready to leave hospital, as well as increasing the number of people relying on health services who could live within the community with additional support to undertake daily tasks. In fact analysis by the Institute of Fiscal Studies found that reductions in social care spending on people aged 65 and over led to increased use of accident and emergency services, both in terms of the average number of visits per resident and the number of individual patients visiting A&E each year (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018).

Closer working between health and social care services has the potential to make care more streamlined and personalised for patients and service users. Nevertheless, integrating services across health and social care is complex because the services have different funding routes, cultures and lines of accountability. Despite this, local services can work more closely together via structural integration, alliances and local partnerships, but solutions work best when locally led.

The provider landscape

Against the backdrop of system working, and in response to severe workforce shortages and financial restraints, many trusts are considering how they can best work together within, and across boundaries. The options for trust to trust collaboration are hugely varied. They might include:

- partnerships and alliances – involving agreements for staff passports for example

- more formal alliances to share or standardise back office services

- collaboration on clinical pathways

- shared posts including chief executive and/or chairs

- a group model

- a merger.

As organisations work more closely together, further questions about structural integration are bound to arise – for instance, should provider organisations explore formal mergers or develop informal grouping arrangements? Would it be helpful for provider chairs to have dual roles within other organisations? Should providers pursue ’vertical’ integration arrangements between primary or community care and acute services, or ’horizontal’ arrangements between community and mental health services, and are these terms even still helpful when integration is being explored at the level of the system and the care pathway?

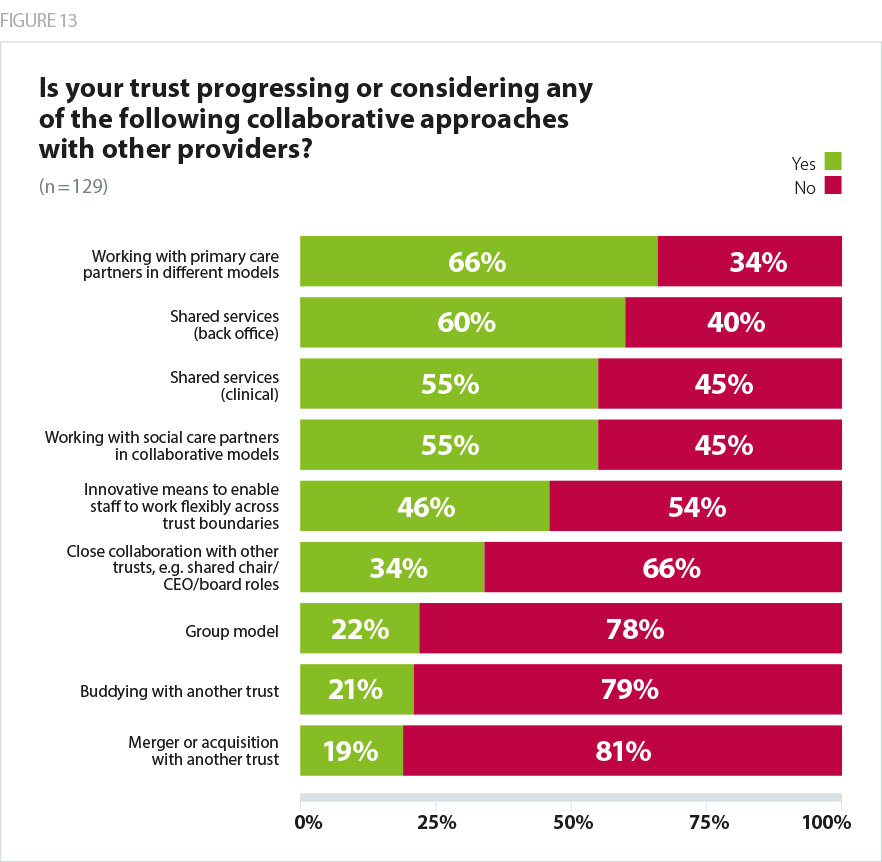

When we asked which types of collaborative approach were under consideration locally, the most common response was "working with primary care in different models, including primary care networks, structural integration and other approaches", which two thirds (66%) were considering, and 'shared services – back office' (60%). Only a fifth said they were exploring a merger or acquisition with another trust (19%) or buddying with another trust (21%).

We have shared a chief executive from July 2019, and have been in a buddy relationship since April 2019 and this is working well so far - working with PCNs and social care through the community services redesign programme.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust

Taking advantage of technology to transform

The digital agenda presents immediate opportunities for greater efficiency and quality improvement in healthcare. However, in order to deliver the objectives of the plan, trusts are also laying the foundations for full digital transformation which will fundamentally change the way services are delivered.

More effective use of digital technology and approaches enables better decision making, whether this means using digital population health tools to inform large decisions on service configuration, or using clinical decision support tools to answer more granular questions about the care provided to individual patients.

Much of the potential for improvement is data-driven, as new digital technologies tend to lead to better data being captured and more effective utilisation. However, other improvements will be driven by the introduction of new systems which lead to different ways of working. For example, electronic patient records standardise and formalise certain processes that sometimes are missed when using paper and pen. Shared care records, such as those used by local health and care record exemplar sites, will play an important role in ensuring all professionals have a full picture of the care an individual is receiving.

Digital is also changing the way patients receive care and interact with the NHS. One of the big shifts here is telemedicine, which is transforming the outpatient model, particularly in more rural areas, meaning patients are spared having to travel long distances to hospital sites. In addition to this, new apps such as online booking systems are changing the way patients engage with providers.

Digital technologies are also improving patient flow, and boost the productivity of inpatient departments. For example, new radio frequency identification technology can help staff to process beds much more quickly, improving overall bed capacity and maximising the use of equipment. Digital technology is also playing a role in driving greater clinical engagement by changing the way clinicians think about health and how they deliver care. In the community sector, nurses and carers are able to use technology to deliver care by video-link in remote settings and within patients' homes.

This progress puts providers on the path to the target level of digitisation set out in the long term plan. In delivering these changes and putting in place more sophisticated IT infrastructure, the sector can prepare itself for full transformation which will include artificial intelligence, robotics and machine learning.

How providers are responding

Trusts are playing an active leadership role within ICS and STPs, often leading key areas of pathway redesign, and helping to navigate arrangements for specialised services and ambulance footprints which cross the boundary of the ICS and STP.

Many trusts are exploring new arrangements with local and national commissioners, as CCGs seek to become more strategic in their focus, and the national commissioners seek to devolve both budgets and responsibility closer to where services are delivered and with greater involvement from clinical experts in the field who are employed by providers. This has been particularly noticeable in the mental health specialised commissioning pilots where lead providers have worked with a network to deliver tertiary services to a population covering a number of STP areas, often realising significant efficiencies and improving quality.

At a more local level, trusts are adopting different approaches to support the delivery of more integrated care. These range from structural solutions, such as the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust which has acquired a number of GP practices, and now offers an integrated service with primary care, or Torbay and South Devon which operates an integrated model for acute, community and social care services – to alliances such as the Harrogate and Rural Alliance in which Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust are working with its local partners to keep people out of hospital, and keep them well in the long term, through a set of jointly managed core services.

What does this mean for patients and service users?

A population-based approach to health has the potential to ensure that local populations receive services which are much more appropriately targeted to their health needs. Services that are more supportive of a preventative approach and address the wider determinants of health (via services such as education, transport, housing) and support individuals to make healthy choices.

A more collaborative approach to delivering services within, and across, local systems has the potential to develop much more integrated and personalised care for patients and service users who frequently experience services that are disjointed, particularly when their condition requires them to access services from multiple providers. Disjointed care manifests itself for patients when information such as notes and test results are not shared effectively between different organisations, when staff involved in a patient's care are not sufficiently informed of the activities of colleagues working with the same patient in different teams or organisations, and when there is no overall coordination of management of the patient's care across the different bodies involved in providing the care.

Digital technology offers the opportunity for more efficient care, ensuring the tax payer gets better value for money, better outcomes from the latest innovations in medical technology, and more personalised care from digital technologies enabling individuals to interact better with the professionals providing their care.