Summary

Trust boards' core priority remains the quality of care they provide to patients and service users. This key priority has been supported by almost a decade of national and local focus on improving patient safety, organisational learning and more recently, quality improvement methodologies. In the past three years, CQC quality ratings of trusts have improved overall despite a challenging context. Trust boards and their staff put in a considerable amount of hard work to raise standards and be recognised as well-led organisations. In 2018, CQC reported that despite the continued growth in demand for services, financial constraints and workforce shortages, quality overall had been maintained and in some cases improved, often thanks to "the focus and hard work of care staff and their leadership teams".

Despite this, in 2018 public satisfaction with the NHS fell to 53%, the lowest level since 2007. CQC has highlighted the variability in access to services across the country and an 'integration lottery' dependent on the strength of relationships between local partner organisations. Although the quality of patient care and clinical outcomes are now measurably better for key major conditions than they were a decade ago, research into cancer survival rates and other international comparators show where the UK is still lagging behind the health systems in many of our European and Commonwealth counterparts.

Alongside a clinical review of access standards, the long term plan contains worthy but ambitious proposals and targets for improved outcomes spanning maternity and neonatal care, children and young people’s mental health, learning disability and autism, cancer services, adult mental health, respiratory disease, stroke services, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The successful implementation of these plans will depend on how far the health and care sector can address the mismatch between demand and capacity across the NHS, coupled with addressing workforce challenges, which have a direct impact on patient experience and access to timely care.

The Provider Challenge

Patient safety and culture

We know that quality of care is impacted by a trust board's ability to create a transparent, 'just' and inclusive culture in which staff feel empowered to both raise concerns and innovate. However, in its new patient safety strategy published in July, NHS Improvement warns that the NHS "does not know enough about how the interplay of how normal human behaviour and systems determine patient safety". The strategy highlights a tendency for people to fear blame and close ranks, rather than maximising what goes right and focusing on the need to improve.

Trusts therefore face a challenge in seeking to create an environment in which staff feel empowered to raise issues of concern, or to flag mistakes they have made, without fear of blame despite intense operational pressures. In recent years, there has been much more focus from trust boards on developing 'bottom up' quality improvement methodologies to create a culture of continuous learning and improvement and to empower staff to take action to improve patient care.

One of the challenges facing trust boards as they seek to embed a transparent culture of continuous improvement, is the sheer number of competing priorities required by the national bodies, which are often ambitious, considering workforce and funding constraints. Trusts are expected to keep services running day to day and at the same time:

- facilitate cultural shifts across multi-site and multidisciplinary organisations

- improve and innovate in clinical practice

- build new relationships with local, regional and national system partners

- operationalise numerous elements of the long term plan, including playing an active role in system working and contributing to system plans which will transform the way that services are designed, commissioned and delivered for local populations.

Within the current operational context, it is also important that leaders at all levels of the system, nationally, regionally and locally model constructive, collaborative behaviours. In addition, the national policy and regulatory environment should be supportive of focusing on service improvement and innovation, as opposed to unnecessarily burdensome performance management approaches which can form a resource intensive distraction for boards and frontline staff who are already stretched to deliver multiple priorities.

The impact of rising demand

The demand for health and care services has been increasing year on year as the population grows and ages, resulting in a fundamental mismatch between capacity within the NHS and the number of people trying to access services. The issue is not limited to one part of the provide sector, nor is it just about increasing bed capacity in hospitals or in the community. The following figures illustrate clearly the pressures facing the provider sector as a whole:

- the number of people in contact with NHS funded secondary mental health, learning disabilities and autism services on 30 June 2019 was nearly 1.4 million, an increase of 50,524 compared to the average number of people in contact at the end of each month between June 2018 and May 2019

- there were 1.6 million new referrals to psychological talking therapy services in 2018-19; 11.4% more than in 2017-18

- in a survey of mental health trusts we conducted at the end of last year, an overwhelming majority (81%) of trust leaders said they are not able to meet current demand for community child and adolescent mental health services and 58% said the same for adult community mental health services

- emergency admissions to acute hospitals increased by 6% from 2017/18 to 2018/19, resulting in an additional 352,530 hospital stays on the previous year

- the number of people on the waiting list for diagnostic tests has grown by 16% from June 2017 to June 2019

- there was a 4% increase in the number of calls received by ambulance services between April to August 2019 when compared to the same period last year

- demand in the community is harder to measure due to the lack of available data. However, in a survey of community trusts we conducted last year, 59% of trusts said their local community service provision was not able to meet the current demand for adult community services. Half of respondents also said the demand for planned community services such as physiotherapy and podiatry was not being met. One trust leader that we interviewed said that demand for some services had gone up by almost 50%.

The mismatch between capacity and demand was unsurprisingly a key concern in responses to this year’s survey, with 61% of respondents saying they were worried about whether their trust had the capacity to meet demand over the next 12 months. Only a fifth of respondents were confident that this would be the case. Respondents from acute trusts (77%) were more likely to be worried about their capacity to meet demand over the next 12 months than those from other types of trust.

We have seen massive growth in demand over the past year (18% elective referrals, 11% A&E) and it is not slowing down. Estate issues are a particular concern as we have now run out of space and can't get our pre-approved capital loans released. Workforce is the other concern as we cannot grow our staffing levels fast enough to keep pace with demand either.

Acute trust

The main concern is workforce shortages but we also have bed capacity shortage and a capital case for a new ward which has been stalled for two years, first by lack of national capital and then by freezing of local capital.

Acute trust

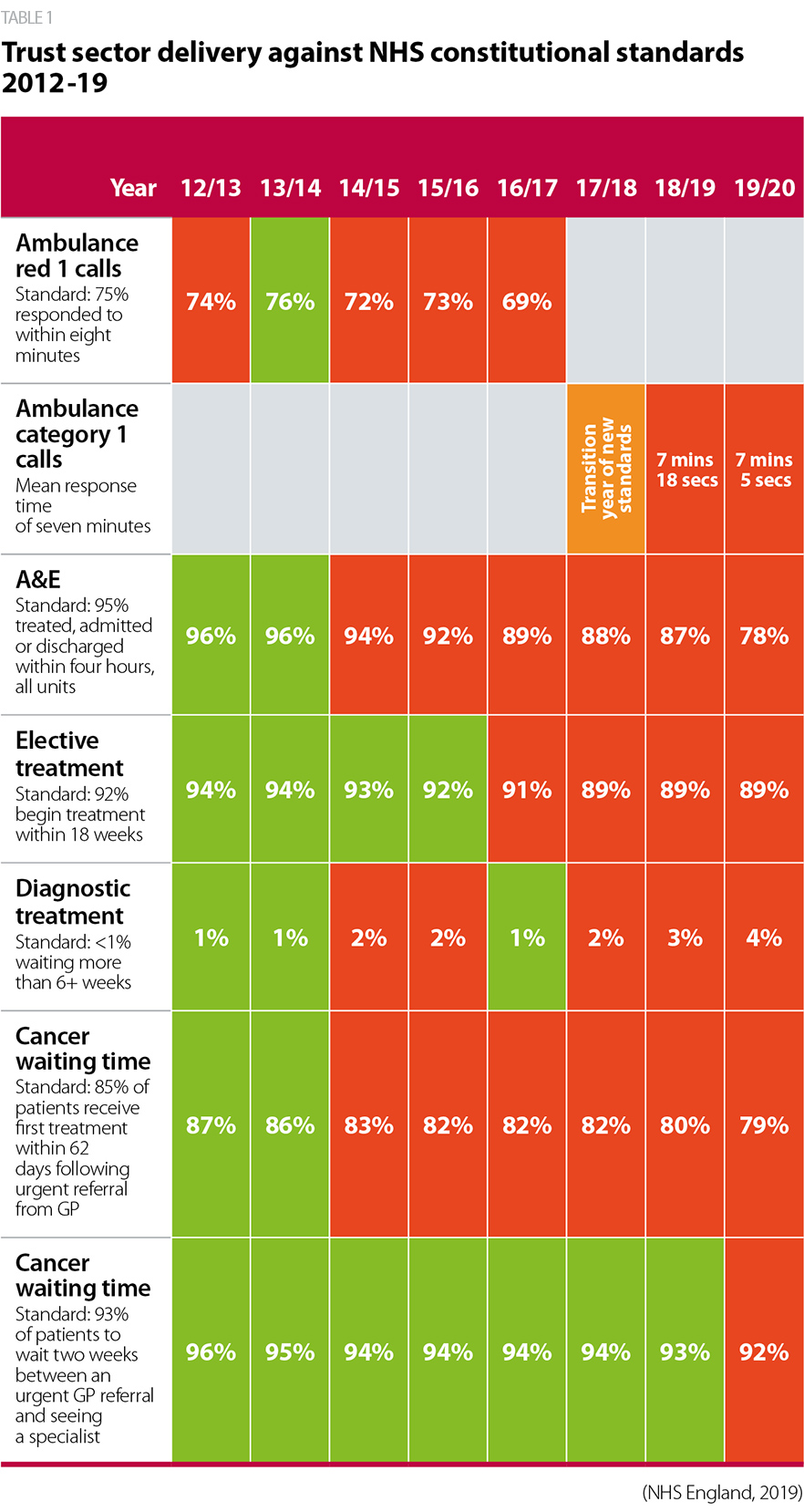

The impact of rising demand and workforce challenges is evident in how the sector is performing against key waiting time standards. As demonstrated below, the sector has been performing more poorly against the ambulance, A&E, elective care, cancer and diagnostic constitutional standards in the past few years. Mental health trusts also tell us that waiting times for psychological therapies, and the use of out of area placements (OAPs) are increasing as demand for care outstrips the capacity trusts have to respond in a timely way.

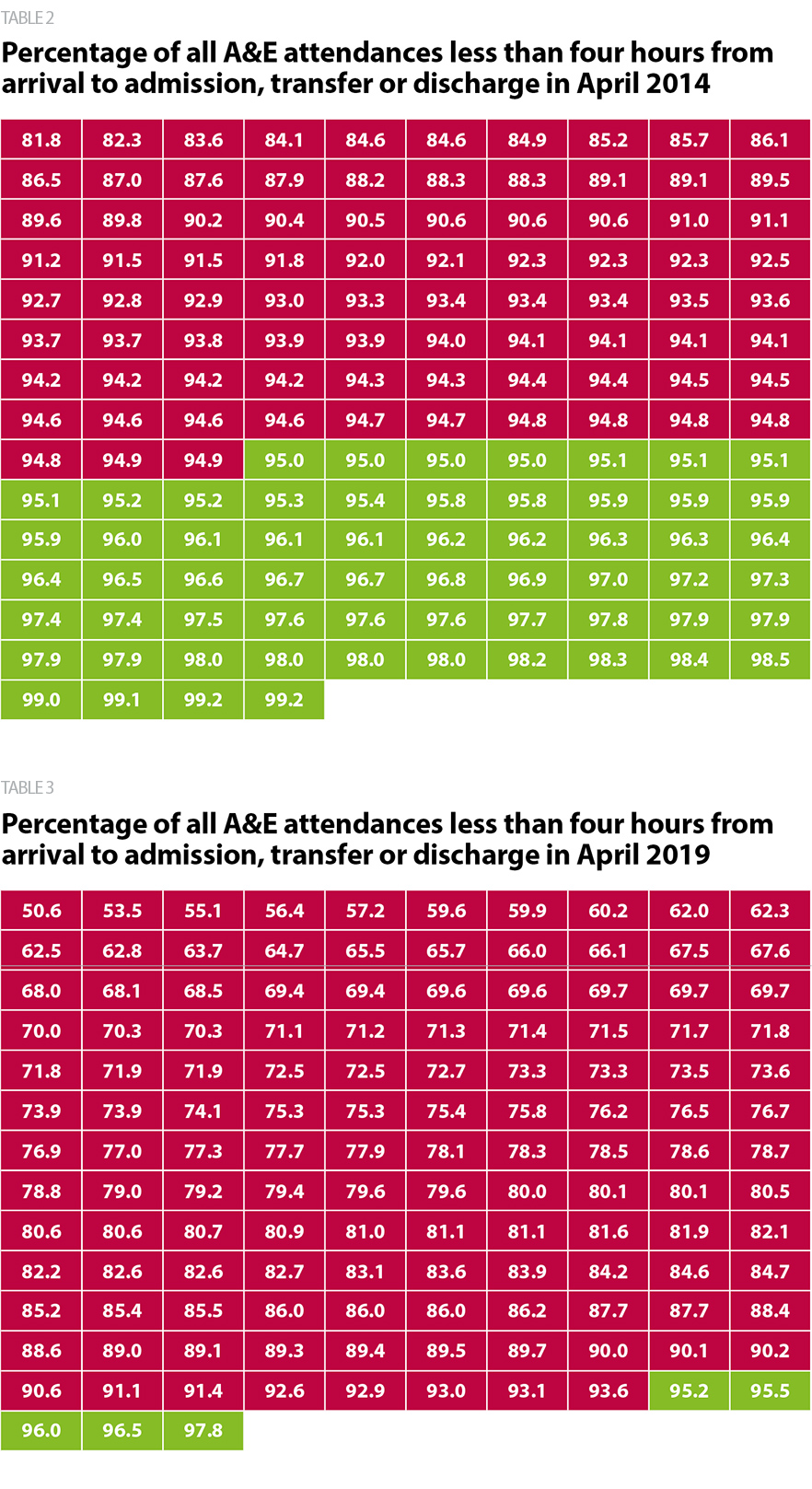

Delivering key access standards is difficult for the majority of trusts. For example, in April 2014, 61 providers with a type 1 A&E department met the four-hour standard in A&E. By April 2019, this figure fell to just five as shown in figures 8 and 9. For mental health trusts, we also know that increasing numbers have to resort to placing service users out of area as they do not have capacity. These operational challenges are not confined to one sector or region.

However, trust leaders remain relatively optimistic for the future. When asked to consider whether their trust’s performance against targets would improve or deteriorate in the next 12 months, 48% of respondents thought it would improve, 30% felt it would stay the same and 21% said it would deteriorate. Results for this question were broadly similar to 2017, and markedly higher than in 2016, when only 30% of respondents thought performance would improve. This may be a reflection of the additional funding for the sector provided via recent changes to the funding balance between CCGs and providers or the additional funding provided for the NHS overall within the long term plan.

We have turned a corner, and have foundations on which to build, but the continuing pressure and need to react means that it is hard to get ahead of the curve. Refreshed executive leadership is providing added impetus, and there is a rising mood of confidence and positivity.

Acute trust

Our cancer waits will improve considerably as we are redesigning all our main pathways, we won't be able to afford additional capacity, so performance is dependent upon redesign work rather than buying people or kit.

Acute trust

Recovering performance and delivering the long term plan

The long term plan contains a large number of proposals and targets for improved outcomes across a wide range of clinical areas and implementing these plans, while at the same time recovering performance, will be a critical task for trust leaders in the coming years.

Transformation at scale will take time and investment beyond the additional funding the government has provided. The sector will need support from national bodies to prioritise and their success will depend to a significant extent on service transformation, system working and efforts to better manage demand across health and care.

NHS England and NHS Improvement launched a clinical review of NHS access standards in February 2019 (NHS England, 2019d), with a commitment to review existing constitutional standards and to seek to develop new measures for mental health. Alongside this, the long term plan makes a commitment to introduce new standards for community services including investment to improve the responsiveness of community health crisis response within two hours of referral (where judged clinically appropriate) and reablement care within two days of referral for those patients judged to need it. The aims and objectives of the review are commendable, and it is right that we reflect modern clinical practice in the access standards the service sets out to the public in the NHS constitution. However, it will be important to ensure the process of reviewing the standards is transparent, rigorous and inclusive. It will also be key to ensure any new measures are fully resourced and do not unintentionally add further pressure to overstretched frontline services.

How providers are responding

Over the past few years, the provider sector has significantly deepened its understanding of how organisational conditions such as good leadership, a just culture, an engaged and diverse workforce all serve to improve patient outcomes and patient experience.

Trust boards are continuing to develop cultures where people are encouraged to innovate and speak up in line with the national patient safety strategy. Trusts are innovatively using quality improvement methods and applying human factors and nudge theories to better understand human behaviour. This is enabling trusts to improve patient flow, adapt patient pathways, define new care models, change patient behaviour and improve staff engagement.

Part of the important necessary culture shift within the NHS is the need to create a diverse and inclusive workforce. There are a range of barriers that trusts face in this area, including the make-up of the board itself not reflecting the diversity of the wider workforce or the local population. Updating trust HR and working policies, engaging with staff through equality and diversity forums or inclusion cafes, implementing initiatives such as reverse mentoring or coaching, are just some of the steps NHS leaders are currently taking to build the foundations to foster an inclusive workplace and begin to provide inclusive leadership.

What does this mean for patients and service users?

Use of quality improvement methodologies by trusts, such as Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, and Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, has the potential to help build a culture of continuous improvement which will be of direct benefit to patients, service users and staff. We know there is a clear link between staff engagement and the quality of care provided, so the more trusts can do to support and empower every member of their staff team, the better the environment in which to provide high quality care.

However, without a clearer sense of the future direction of the NHS, and a more public debate about what can be delivered within the funding envelope available, frustrations with the service may continue to rise. Growing waiting times and an over stretched workforce seeking to care for rising numbers of patients both have a clear and very direct impact on patient experience, timely access to care and outcomes.