Successfully implementing process improvement methods (like Lean for example) relies on both technical capability (i.e. the knowledge people have of principles, practices and tools), and social connectedness.

Healthcare organisations can be complex places to work. Social and professional relationships are commonly shaped by power, status and hierarchical position; very often those on the frontline of care delivery do not interact – formally or informally – with those working in other specialities and departments, or members of the executive leadership team. From a continuous improvement perspective, this means opportunities to share knowledge and collaborate for quality improvement are suppressed.

Our analysis revealed the importance of connecting diverse professional groups for regular and informal interaction. Specifically, we found a high degree of connectedness among healthcare professionals was associated with a high degree of informal knowledge exchange, a high capacity for collaboration, and a sustainable quality improvement culture.

Analysing social networks

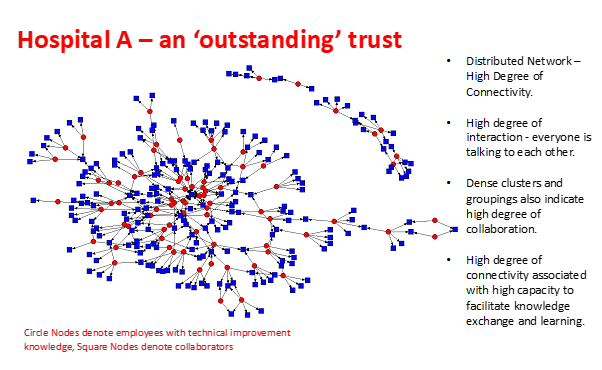

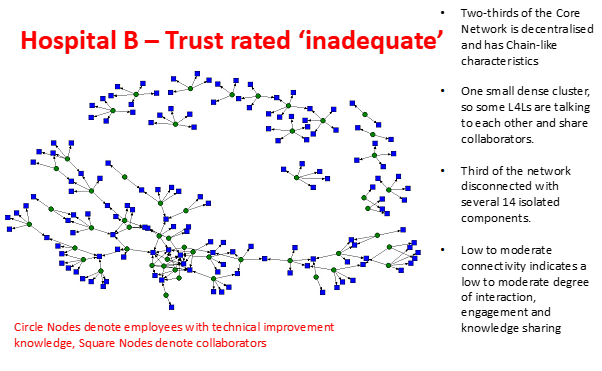

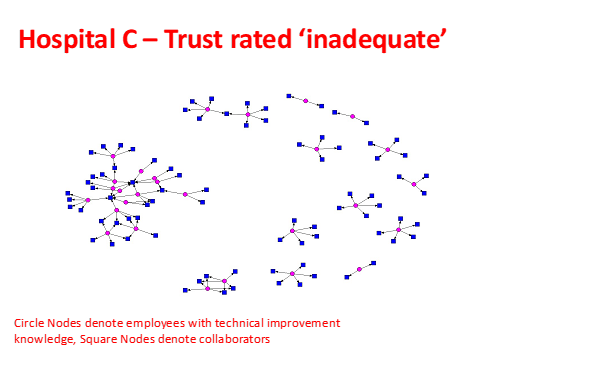

The graphics below represent the social networks present in three English NHS hospitals trusts in 2019.

These social networks were drawn from data collected via a simple template that asked participants to name between two and five people they talk to about improvement and also name between two and five people who talk to them about improvement. Data was analysed using the comprehensive social network software package UCINET.

So what does this look like in practice?

At a glance, we can see that hospital A looks strikingly different to hospitals B and C. Hospital A's relationships are plentiful and the network is considered 'dense'. In effect, everyone is talking to each other about improvement; the capacity for mutual knowledge exchange and collaboration for improvement is high.

Hospital B's network graph depicts a network that is considerably less dense, with a high number of participants disconnected from the 'core' network. Hospital C's network is very sparse, clinical and non-clinical leaders with technical expertise appear isolated. Very little improvement related talk is occurring at hospital C.

Very simply, when a social structure is dense and stable, then the capacity for knowledge exchange, learning and collaboration is high.

Very simply, when a social structure is dense (i.e. lots of relationships are present) and stable (i.e. relationships are based on reciprocal knowledge exchange), then the capacity for knowledge exchange, learning and collaboration is high. When relationships are sparse, and/or represent 'cliques and hierarchies', knowledge exchange is suppressed and opportunities for collaboration are greatly diminished.

While trusts will know that these ratings are far from the only measure of success we might use, it is notable to say that in 2019 hospital A was rated 'outstanding' by Care Quality Commission (CQC). Hospitals B and C were each rated 'inadequate'.

Drilling down

Social network analysis provides a vivid illustration of the structure of social networks for knowledge exchange. However, it also provides useful insight to the nature of knowledge exchange.

For example, if we talk further about hospital B – underpinning analysis shows that while people are talking about improvement, the majority of relationships as classified as what we would call 'simple brokering'. Simple brokering refers to an individual who is communicating to others in a manner representative of 'messenger'. In other words, communication is one-directional and often on a 'need to know' basis.

By contrast, hospital A has high levels of what we call reciprocal brokering relationships. These extend within and beyond their professional teams and departments, indicating an abundance of relational connections that are both mutual and collaborative.

It's good to talk

Social network analysis has shown that a densely connected network, where relationships are mutually reciprocal, are associated with high performing organisations. This highlights how important it is to create opportunities for building reciprocal relational connections – it's fundamental to developing a culture of improvement in organisations. At hospital A, there were many examples of formal routines designed to foster informal talk that spans departments and managerial hierarchy.

Getting together

For example, inviting groups of clinicians (eg. matrons, ward managers, junior doctors) to breakfast with the chief executive and their team, or bringing clinical leads together for pizza once a month presents a mechanism for encouraging 'talk' to happen across organisational departments, in informal ways. This promotes a social structure that is significantly different to the messenger style of communication that characterizes professional bureaucracies observed at hospitals B and C.

To return to the question posed in the headline… we are not suggesting that executives eating pizza with staff on a routine basis will automatically lead to a high performing organisation!

To return to the question posed in the headline… we are not suggesting that executives eating pizza with staff on a routine basis will automatically lead to a high performing organisation! But, the principle of fostering informal talk as part of formal routines represents an effective mechanism for breaking down silos, sharing knowledge for collaborative improvement and fostering connectedness between those that steer the organisation at a strategic level, and those who lead the organisation at an operational level (and at the frontline of service delivery).

Sharing the same goal

Interviews with executive leaders at hospital A reflect on the organisation's journey from 'the worst in the country on every performance measure in 2010', to becoming one of the best in 2019. Crucially they cite hospital values of 'one team', in other words that everybody works together towards the same shared and unwavering goal. That goal is to provide the best possible care to the patient. Hospital A is not a hierarchical organisation, but there is no doubt that the organisation is 'well-led', or that the delivery of high quality patient care is the reason this organisation has worked hard to foster a 'one-team' collaborative improvement culture.

Getting out and about

There are many ways in which NHS boards can use formal routines to create informal spaces for talk. For example, weekly or monthly leadership walks, when executive and/or non-executive directors visit departments and wards to speak informally with staff as they go about their work, provide an excellent opportunity to get to know staff, understand the work that gets done, the challenges faced, and explore ways to work together to continuously improve the quality and safety of patient care.

For the huge majority of trusts, these kinds of activities have been made more difficult or impossible during the pandemic. But as we hopefully begin to move into a different phase, it seems even more important than ever to consider how you might deliver these opportunities for informal engagement and knowledge-sharing, which leads to better connectivity and ultimately, improvement of service and quality of care.

If you would like to find out more about social network analysis and commission an assessment, please contact info@arcturaconsulting.com.

About the author